Meet JPL Interns | July 23, 2020

JPL Interns Are Working From Home While 'Going the Distance' for Space Exploration

Most years, summertime at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory arrives with an influx of more than 800 interns, raring to play a hands-on role in exploring Earth and space with robotic spacecraft.

Perhaps as exciting as adding NASA to their resumes and working alongside the scientists and engineers they have long admired is the chance to explore the laboratory's smorgasbord of science labs, spacecraft assembly facilities, space simulators, the historic mission control center and a place called the Mars Yard, where engineers test drive Mars rovers.

But this year, as the summer internship season approached with most of JPL's more than 6,000 employees still on mandatory telework, the laboratory – and the students who were offered internships at the Southern California center – had a decision to make.

"We asked the students and the mentors [the employees bringing them in] whether their projects could still be achieved remotely and provide the educational component we consider to be so crucial to these experiences," said Adrian Ponce, deputy section manager of JPL's Education Office, which runs the laboratory's STEM internship programs.

The answer was a resounding yes, which meant the laboratory had just a matter of weeks to create virtual alternatives for every aspect of the internship experience, from accessing specialized software for studying Earth and planetary science to testing and fine-tuning the movements of spacecraft in development and preparing others for launch to attending enrichment activities like science talks and team building events.

“We were able to transition almost all of the interns to aspects of their projects that are telework-compatible. Others agreed to a future start date,” said Ponce, adding that just 2% of the students offered internships declined to proceed or had their projects canceled.

Now, JPL's 600-plus summer interns – some who were part-way through internships when the stay-at-home orders went into effect, others who are returning and many who are first-timers – are getting an extended lesson in the against-the-odds attitude on which the laboratory prides itself.

We wanted to hear about their experiences as JPL's first class of remote interns. What are their routines and home offices like in cities across the country? How have their teams adapted to building spacecraft and doing science remotely? Read a collection of their responses below to learn how JPL interns are finding ways to persevere, whether it's using their engineering skills to fashion homemade desks, getting accustomed to testing spacecraft from 2,000 miles away or working alongside siblings, kids, and pets.

Courtesy of Jennifer Bragg | + Expand image

"I am working with an astronomer on the NEOWISE project, which is an automated system that detects near-Earth objects, such as asteroids. The goal of my project is to identify any objects missed by the automated system and use modeling to learn more about their characteristics. My average day consists of writing scripts in Python to manipulate the NEOWISE data and visually vet that the objects in the images are asteroids and not noise or stars.

My office setup consists of a table with scattered books, papers, and pencils, a laptop, television, a child in the background asking a million questions while I work, and a bird on my shoulder that watches me at times."

– Jennifer Bragg will be studying optics at the University of Arizona as an incoming graduate student starting this August. She is completing her summer internship from Pahoa, Hawaii.

Courtesy of Radina Yanakieva | + Expand image

"I'm helping support the Perseverance Mars rover launch this summer. So far, I have been working remotely, but I'm lucky enough to have the opportunity to go to Pasadena, California, in late July to support the launch from JPL! On launch day, I will be in the testbed, where myself and a few other members of my group will be 'shadowing' the spacecraft. This means that when operators send their commands to the actual spacecraft, when it’s on the launch pad and during its first day or so in space, we'll send the same instructions to the test-bed version. This way, if anything goes wrong, we'll have a high-fidelity simulation ready for debugging.

I have a desk in my bedroom, so my office setup is decent enough. I bought a little whiteboard to write myself notes. As for my average working day, it really depends on what I'm doing. Some days, I'm writing procedures or code, so it's a text editor, a hundred internet tabs, and a messenger to ask my team members questions. Other days, I'm supporting a shift in the test bed, so I'm on a web call with a few other people talking about the test we're doing. Luckily, a large portion of my team's work can be done on our personal computers. The biggest change has been adding the ability to operate the test bed remotely. I'm often amazed that from New York, I can control hardware in California.

I was ecstatic that I was still able to help with the Perseverance Mars rover mission! I spent the second half of 2019 working on launch and cruise testing for the mission, so I'm happy to be able to see it through."

– Radina Yanakieva is an undergraduate student studying aerospace engineering at Georgia Tech and interning from Staten Island, New York.

Courtesy of Aditya Khuller | + Expand image

"Our team is using radar data [from the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft] to find out what lies beneath the large icy deposits on Mars' south pole. My average day consists of analyzing this radar data on my computer to find and map the topography of an older surface that lies below the ice on Mars’ south pole, while my plants look on approvingly.

I was delighted to be offered the chance to work at JPL again. (This is my fourth JPL internship.) Even though it's better to be 'on lab,' it is an honor to get to learn from the coolest and smartest people in the world."

– Aditya Khuller is a graduate student working toward a Ph.D. in planetary science at Arizona State University and interning from Tempe, Arizona.

Courtesy of Breanna Ivey | + Expand image

"I am working on the Perseverance Mars rover mission [launching this summer]. As a member of the mobility team, I am testing the rover's auto-navigation behaviors. If given a specific location, flight software should be able to return data about where that location is relative to the rover. My project is to create test cases and develop procedures to verify the data returned by the flight software when this feature is used.

My average day starts with me eating breakfast with my mom who is also working from home. Then, I write a brief plan for my day. Next, I meet with my mentor to discuss any problems and/or updates. I spend the rest of my day at my portable workstation working on code to test the rover's behaviors and analyzing the data from the tests. I have a mini desk that I either set up in my bedroom in front of my Georgia Tech Buzz painting or in the dining room.

If I could visit in person, the first thing I would want to see is the Mars rover engineering model "Scarecrow." I would love to visit the Mars Yard [a simulated Mars environment at JPL] and watch Scarecrow run through different tests. It would be so cool to see a physical representation of the things that I've been working on."

– Breanna Ivey is an undergraduate student studying electrical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology and interning from Macon, Georgia.

Courtesy of Kaelan Oldani | + Expand image

"I am working on the Psyche mission as a member of the Assembly Test and Launch Operations team, also known as ATLO. (We engineers love our acronyms!) Our goal is to assemble and test the Psyche spacecraft to make sure everything works correctly so that the spacecraft will be able to orbit and study its target, a metal asteroid also called Psyche. Scientists theorize that the asteroid is actually the metal core of what was once another planet. By studying it, we hope to learn more about the formation of Earth.

I always start out my virtual work day by giving my dog a hug, grabbing a cup of coffee and heading up to my family's guest bedroom, which has turned into my office for the summer. On the window sill in my office are a number of space-themed Lego sets including the 'Women of NASA' set, which helps me get into the space-exploration mood! Once I have fueled up on coffee, my brain is ready for launch, and I log in to the JPL virtual network to start writing plans for testing Psyche's propulsion systems. While the ATLO team is working remotely, we are focused on writing test plans and procedures so that they can be ready as soon as the Psyche spacecraft is in the lab for testing. We have a continuous stream of video calls set up throughout the week to meet virtually with the teams helping to build the spacecraft."

– Kaelan Oldani is a master's student studying aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan and interning from Ann Arbor, Michigan. She recently accepted a full-time position at JPL and is starting in early 2021.

Courtesy of Ricardo Isai Melgar | + Expand image

"NASA's Deep Space Network is a system of antennas positioned around the world – in Australia, Spain, and Goldstone, California – that's used to communicate with spacecraft. My internship is working on a risk assessment of the hydraulic system for the 70-meter antenna at the Goldstone facility. The hydraulic system is what allows the antenna and dish surrounding it to move so it can accurately track spacecraft in flight. The ultimate goal of the work is to make sure the antenna's hydraulic systems meet NASA standards.

My average day starts by getting ready for work (morning routine), accessing my work computer through a virtual interface and talking with my mentor on [our collaboration tool]. Then, I dive into work, researching hydraulic schematics, JPL technical drawings of the antenna, and NASA standards, and adding to a huge spreadsheet that I use to track every component of the antenna's hydraulic system. Currently, I'm tracking every flexible hydraulic fluid hose on the system and figuring out what dangers a failure of the hose could have on personnel and the mission."

– Ricardo Isai Melgar is an undergraduate student studying mechanical engineering at East Los Angeles College and interning from Los Angeles.

Courtesy of Susanna Eschbach | + Expand image

"My project this summer is to develop a network of carbon-dioxide sensors to be used aboard the International Space Station for monitoring the levels of carbon dioxide that crewmembers experience.

My 'office setup' is actually just a board across the end of my bed balanced on the other side by a small dresser that I pull into the middle of the room every day so that I can sit and have a hard surface to work on.

At first I wasn't sure if I was interested in doing a virtual engineering internship. How would that even work? But after talking to my family, I decided to accept. Online or in person, getting to work at JPL is still a really cool opportunity."

– Susanna Eschbach is an undergraduate student studying electrical and computer engineering at Northern Illinois University and interning from DeKalb, Illinois.

Courtesy of Izzie Torres | + Expand image

"I'm planning test procedures for the Europa Clipper mission [which is designed to make flybys of Jupiter's moon Europa]. The end goal is to create a list of tests we can perform that will prove that the spacecraft meets its requirements and works as a whole system.

I was very excited when I got the offer to do a virtual internship at JPL. My internship was originally supposed to be with the Perseverance Mars rover mission, but it required too much in-person work, so I was moved to the Europa Clipper project. While I had been looking forward to working on a project that was going to be launching so soon, Jupiter's moon Europa has always captured my imagination because of the ocean under its surface. It was an added bonus to know I had an internship secured for the summer."

– Izzie Torres is an undergraduate student studying aerospace engineering and management at MIT and interning from Seattle.

Courtesy of Jared Blanchard | + Expand image

"I am investigating potential spacecraft trajectories to reach the water worlds orbiting the outer planets, specifically Jupiter's moon Europa. If you take both Jupiter and Europa into account, their gravitational force fields combine to allow for some incredibly fuel-efficient maneuvers between the two. The ultimate goal is to make it easier for mission designers to use these low-energy trajectories to develop mission plans that use very little fuel.

I'm not a gamer, but I just got a new gaming laptop because it has a nice graphics processing unit, or GPU. During my internship at JPL last summer, we used several GPUs and a supercomputer to make our trajectory computations 10,000 times faster! We plan to use the GPU to speed up my work this summer as well. I have my laptop connected to a second monitor up in the loft of the cabin where my wife and I are staying. We just had a baby two months ago, so I have to make the most of the quiet times when he's napping!"

– Jared Blanchard is a graduate student working toward a Ph.D. in aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University.

Courtesy of Yohn I. Ellis Jr. | + Expand image

"I'm doing a theory-based project on the topic of nanotechnology under the mentorship of Mohammad Ashtijou and Eric Perez.

I vividly remember being infatuated with NASA as a youth, so much so that my parents ordered me a pamphlet from Space Center Houston with posters and stickers explaining all of the cool things happening across NASA. I will never forget when I was able to visit Space Center Houston on spring break in 2009. It was by far the most amazing thing I have ever witnessed as a youth. When I was offered the internship at JPL, I was excited, challenged, and motivated. There is a great deal of respect that comes with being an NASA intern, and I look forward to furthering my experiences.

But the challenges are prevalent, too. Unfortunately, the internship is completely virtual and there are limitations to my experience. It is hard working at home with the multiple personalities in my family. I love them, but have you attempted to conduct research with a surround system of romantic comedies playing in the living room, war video games blasting grenades, and the sweet voice of your grandmother asking for help getting pans from the top shelf?"

– Yohn I. Ellis Jr. is a graduate student studying electrical engineering at Prairie View A&M University and interning from Houston.

Courtesy of Mina Cezairli | + Expand image

"This summer, I am supporting the proposal for a small satellite mission concept called Cupid’s Arrow. Cupid’s Arrow would be a small probe designed to fly through Venus’ atmosphere and collect samples. The ultimate goal of the project is to understand the “origin story” of Venus' atmosphere and how, despite their comparable sizes, Earth and Venus evolved so differently geologically, with the former being the habitable, friendly planet that we call home and the latter being the hottest planet in our solar system with a mainly carbon dioxide atmosphere.

While ordinary JPL meetings include discussions of space probes, rockets, and visiting other planets, my working day rarely involves leaving my desk. Because all of my work can be done on my computer, I have a pretty simple office setup: a desk, my computer, and a wall full of posters of Earth and the Solar System. An average day is usually a combination of data analysis, reading and learning about Venus, and a number of web meetings. The team has several different time zones represented, so a morning meeting in Pacific time accommodates all of Pacific, Eastern and European time zones that exist within the working hours of the team."

– Mina Cezairli is an undergraduate student studying mechanical engineering at Yale University and is interning from New Haven, Connecticut.

Courtesy of Izabella Zamora | + Expand image

“I'm characterizing the genetic signatures of heat-resistant bacteria. The goal is to improve the techniques we use to sterilize spacecraft to prevent them from contaminating other worlds or bringing contaminants back to Earth. Specifically, I'm working to refine the amount of time spacecraft need to spend getting blasted by dry heat as a sanitation method.

"As someone who has a biology-lab heavy internship, I was quite skeptical of how an online internship would work. There was originally supposed to be lab work, but I think the project took an interesting turn into research and computational biology. It has been a really cool intersection to explore, and I have gained a deeper understanding of the math and analysis involved in addition to the biology concepts."

– Izabella Zamora is an undergraduate student studying biology and computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and interning from Brimfield, Massachusetts.

Courtesy of Leilani Trautman | + Expand image

"I am working on the engineering operations team for the Perseverance Mars rover. After the rover lands on Mars, it will send daily status updates. Every day, an engineer at JPL will need to make sure that the status update looks healthy so that the rover can continue its mission. I am writing code to make that process a lot faster for the engineers.

When I was offered the internship back in November, I thought I would be working on hardware for the rover. Once the COVID-19 crisis began ramping up and I saw many of my friends' internships get cancelled or shortened, I was worried that the same would happen to me. One day, I got a call letting me know that my previous internship wouldn't be possible but that there was an opportunity to work on a different team. I was so grateful to have the opportunity to retain my internship at JPL and get the chance to work with my mentor, Farah Alibay, who was once a JPL intern herself."

– Leilani Trautman is an undergraduate student studying electrical engineering and computer science at MIT and interning from San Diego, California.

Courtesy of Kathryn Chamberlin | + Expand image

"I am working on electronics for the coronagraph instrument that will fly aboard the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. The Roman Space Telescope will study dark energy, dark matter, and exoplanets [planets outside our solar system]. The science instrument I'm working on will be used to image exoplanets. It's also serving as a technology demonstration to advance future coronagraphs [which are instruments designed to observe objects close to bright stars].

I was both nervous and excited to have a virtual internship. I’m a returning intern, continuing my work on the coronagraph instrument. I absolutely love my work and my project at JPL, so I was really looking forward to another internship. Since I’m working with the same group, I was relieved that I already knew my team, but nervous about how I would connect with my team, ask questions, and meet other 'JPLers.' But I think my team is just as effective working virtually as we were when working 'on lab.' My mentor and I have even figured out how to test hardware virtually by video calling the engineer in the lab and connecting remotely into the lab computer."

– Kathryn Chamberlin is an undergraduate student studying electrical engineering at Arizona State University and interning from Phoenix.

Courtesy of Daniel Stover | + Expand image

"I am working on the flight system for the Perseverance Mars rover. The first half of my internship was spent learning the rules of the road for the entire flight system. My first task was updating command-line Python scripts, which help unpack the data that is received from the rover. After that, I moved on to testing a part of the flight software that manages which mechanisms and instruments the spacecraft can use at a certain time. I have been so grateful to contribute to the Perseverance Mars rover project, especially during the summer that it launches!

I have always been one to be happy with all the opportunities I am granted, but I do have to say it was hard to come to the realization that I would not be able to step foot on the JPL campus. However, I was truly grateful to receive this opportunity, and I have been so delighted to see the JPL spirit translate to the online video chats and communication channels. It's definitely the amazing people who make JPL into the place that everybody admires. Most important, I would like to thank my mentor, Jessica Samuels, for taking the time to meet with me every day and show me the true compassion and inspiration of the engineers at JPL."

– Daniel Stover is an undergraduate student studying electrical and computer engineering at Virginia Tech and interning from Leesburg, Virginia.

Courtesy of Sophia Yoo | + Expand image

"I'm working on a project called the Multi-Angle Imager for Aerosols, or MAIA. It's an instrument that will go into lower Earth orbit and collect images of particulate matter to learn about air pollution and its effects on health. I'm programming some of the software used to control the instrument's electronics. I'm also testing the simulated interface used to communicate with the instrument.

I was ecstatic to still have my internship! I'm very blessed to be able to do all my work remotely. It has sometimes proven to be a challenge when I find myself more than four layers deep in virtual environments. And it can be confusing to program hardware on the West Coast with software that I wrote all the way over here on the East Coast. However, I've learned so much and am surprised by and grateful for the meaningful relationships I've already built."

– Sophia Yoo is an incoming graduate student studying electrical and computer engineering at Princeton University and is interning from Souderton, Pennsylvania.

Courtesy of Natalie Maus | + Expand image

"My summer research project is focused on using machine-learning algorithms to make predictions about the density of electrons in Earth’s ionosphere [a region of the planet's upper atmosphere]. Our work seeks to allow scientists to forecast this electron density, as it has important impacts on things such as GPS positioning and aircraft navigation.

Despite the strangeness of working remotely, I have learned a ton about the research process and what it is like to be part of a real research team. Working alongside my mentors to adapt to the unique challenges of working remotely has also been educational. In research, and in life, there will always be new and unforeseen problems and challenges. This extreme circumstance is valuable in that it teaches us interns the importance of creative problem solving, adaptability, and making the most out of the situation we are given."

– Natalie Maus is an undergraduate student studying astrophysics and computer science at Colby College and interning from Evergreen, Colorado.

Courtesy of Lucas Lange | + Expand image

"I have two projects at JPL. My first project focuses on the Europa Clipper mission [designed to make flybys of Jupiter's moon Europa]. I study how the complex topography on the icy moon influences the temperature of the surface. This work is crucial to detect 'hot spots,' which are areas the mission (and future missions) aim to study because they might correspond to regions that could support life! My other work consists of studying frost on Mars and whether it indicates the presence of water-ice below the surface.

JPL and NASA interns are connected through social networks, and it's impressive to see the diversity. Some talks are given by 'JPLers' who make themselves available to answer questions. When I came to JPL, I expected to meet superheroes. This wish has been entirely fulfilled. Working remotely doesn't mean working alone. On the contrary, I think it increases our connections and solidarity."

– Lucas Lange is an undergraduate student studying aerospace engineering and planetary science at ISAE-SUPAERO [aerospace institute in France] and interning from Pasadena, California.

Explore JPL’s summer and year-round internship programs and apply at: jpl.nasa.gov/intern

Career opportunities in STEM and beyond can be found online at jpl.jobs. Learn more about careers and life at JPL on LinkedIn and by following @nasajplcareers on Instagram.

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of STEM Engagement’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

TAGS: Higher Education, Internships, STEM, College Students, Virtual Internships, Telework, Mars 2020 interns, Mars 2020, Perseverance, DSN, Deep Space Network, Mars, Asteroids, NEOWISE, Science, Technology, Engineering, Computer Science, Psyche, International Space Station, ISS, Europa, Jupiter, Europa Clipper, trajectory, nanotechnology, Cupid's Arrow, Proposal, Venus, Planetary Protection, Biology, Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, Dark Matter, Exoplanets, Multi-Angle Imager for Aerosols, MAIA, Earth, Earth science, air pollution, Hispanic Heritage Month, Black History Month, Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Earth Science, Earth, Climate Change, Sea Level Rise

Meet JPL Interns | October 31, 2018

Whether Designing Pumpkins or Extreme Rovers, It's All About Guts

All spacecraft are made for extreme environments. They travel through dark, frigid regions of space, battle intense radiation and, in some cases, perform daring feats to land on mysterious worlds. But the rover that Tonya Beatty is helping design for Venus – and other so-called extreme environments – is in a class all its own. Venus is so inhospitable that no spacecraft has ever lasted more than about two hours on the surface. So Beatty, an intern at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and an aerospace engineering student at College of the Canyons, is working to develop a new kind of rover that's powered mostly by gears rather than sensitive electronics. We caught up with Beatty just before she embarked on another engineering challenge – JPL's annual Halloween pumpkin-carving contest – to find out what it takes to turn an impossible idea into a reality.

Meet JPL Interns

Read stories from interns pushing the boundaries of space exploration and science at the leading center for robotic exploration of the solar system.

What are you working on at JPL?

I'm working with a team on the HAR-V project, which stands for Hybrid Automaton Rover-Venus. It’s a study to develop a rover meant to go to Venus. I'm assisting in the development of mechanical systems and mechanisms on the prototype, using clockwork maneuvers. This rover will use minimal electronics, so when I say clockwork, I mean gears and anything that does not rely on electronics.

Why is this rover not relying on electronics and relying more on a gear system?

The environment on Venus includes sulfuric acid clouds, a surface pressure about 90 times what it is on Earth and a temperature that exceeds 800 degrees Fahrenheit. The materials in most electronics would melt in that extreme environment, so that's why we're trying to go mechanical. The previous landers that have gone to Venus have relied on electronics, and the one that lasted the longest only lasted 127 minutes, whereas ours, using the mechanical design, is projected to last about six months. So that's why we're going with this design.

What does a typical day look like for you?

A typical day for me consists of designing mechanisms, designing mechanical systems, ordering parts for those mechanical systems, testing them on the active prototype that we have and redesigning if necessary. It's kind of a mixture of all that, depending on where we're at in each step.

What is the ultimate goal of your project?

My personal goal with this internship is to connect the things I'm learning in school to real-world applications, as well as see what it would be like to be an aerospace engineer. Specific to the HAR-V study, my goals are to design a power-transfer mechanism, redesign the reversing mechanism on the rover itself, and redesign the obstacle avoidance mechanism. Those are all things that I'm now learning as I'm doing the internship, which is great. I love learning new things.

As for HAR-V itself, the goal is to be able to withstand those extreme environments for longer than 127 minutes and retrieve the groundbreaking data that we've been wanting from Venus but haven't been able to get because we haven't had the time we need [with previous landers].

Personally, at 19, I never thought that I would be working on a rover for Venus at NASA. By sharing my story, I hope people take away that some of the things they might think are impossible are really right there. They’ve just got to reach for it.

What's the most JPL or NASA unique experience that you've had so far?

As much as I'd like to say something cool like watching the rovers being tested, I have to say it's the deer. Every day, wherever I go – to laser-cut something or go get a coffee – I see deer. One day I saw six. I just think that's so unique because it’s something I never expected to get from this experience. And I think it’s unique to JPL.

Beatty participated in JPL's annual Halloween pumpkin-carving contest and, with her team, won first place with this pumpkin modeled after the character Miguel from the movie "Coco." Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | + Expand image

Speaking of unique experiences, your group holds an annual pumpkin-carving contest and makes some amazing creations. Are you planning to participate in the contest this year?

I actually just got the emails today. I didn't know this was a JPL thing. It's a big deal! So, yes, I'd like to!

Do you know what your team is planning to make? Don’t worry, we won’t share this until after the contest, so it won't leak to any competitor.

We're making Miguel from [the movie] “Coco” with his guitar, and we're going to try and make it move.

How does designing a mechanical or creative pumpkin compare to designing a rover for Venus?

Well, with a pumpkin, I would care about how it looks, whereas with the rover, I care about how it functions. A pumpkin has real guts, and a rover has metaphorical guts. It's got to keep on going. But I think the biggest similarity is the creativeness between both of them, because you have to be creative to make an innovative pumpkin. Just like when you design a rover, you have to be creative; you can't just be smart. You have to have those creative ideas. You have to think outside of the box to actually design efficient and effective components, and you can't just give up. When you have a failed attempt, you try it again.

Do you have any tips for anyone who want to make a creative pumpkin?

Create a Halloween Pumpkin Like a NASA Engineer

Get tips from NASA engineers on how to make an out-of-this-world Halloween pumpkin.

Don't be afraid of your ideas. Sometimes we limit ourselves because we're like, “You know that's too crazy. We shouldn't do that,” but it takes crazy ideas to be an engineer and it takes crazy ideas to carve a good pumpkin.

OK, back to your internship: How do you feel you're contributing to NASA missions and science?

I think my active participation in the rover study is helping contribute to NASA-JPL missions, because something I have designed could very well be on an actual rover that could go to Venus, that would retrieve data, that does help NASA. So I think in that sense, I am contributing.

One last fun question: If you could travel to any place in space, where would you go, and what would you do there?

I would go to Europa. I would like to see first-hand if there is an ocean and if there's an environment that could sustain life. Chemistry has always interested me, so I would love to see that up close and analyze everything.

Explore JPL’s summer and year-round internship programs and apply at: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/edu/intern

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of Education’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

TAGS: Women in STEM, Higher Education, Internships, Students, Engineering, Rovers, Venus, Women at NASA

Teachable Moments | May 6, 2016

A Teachable Moment You Can See! The Transit of Mercury

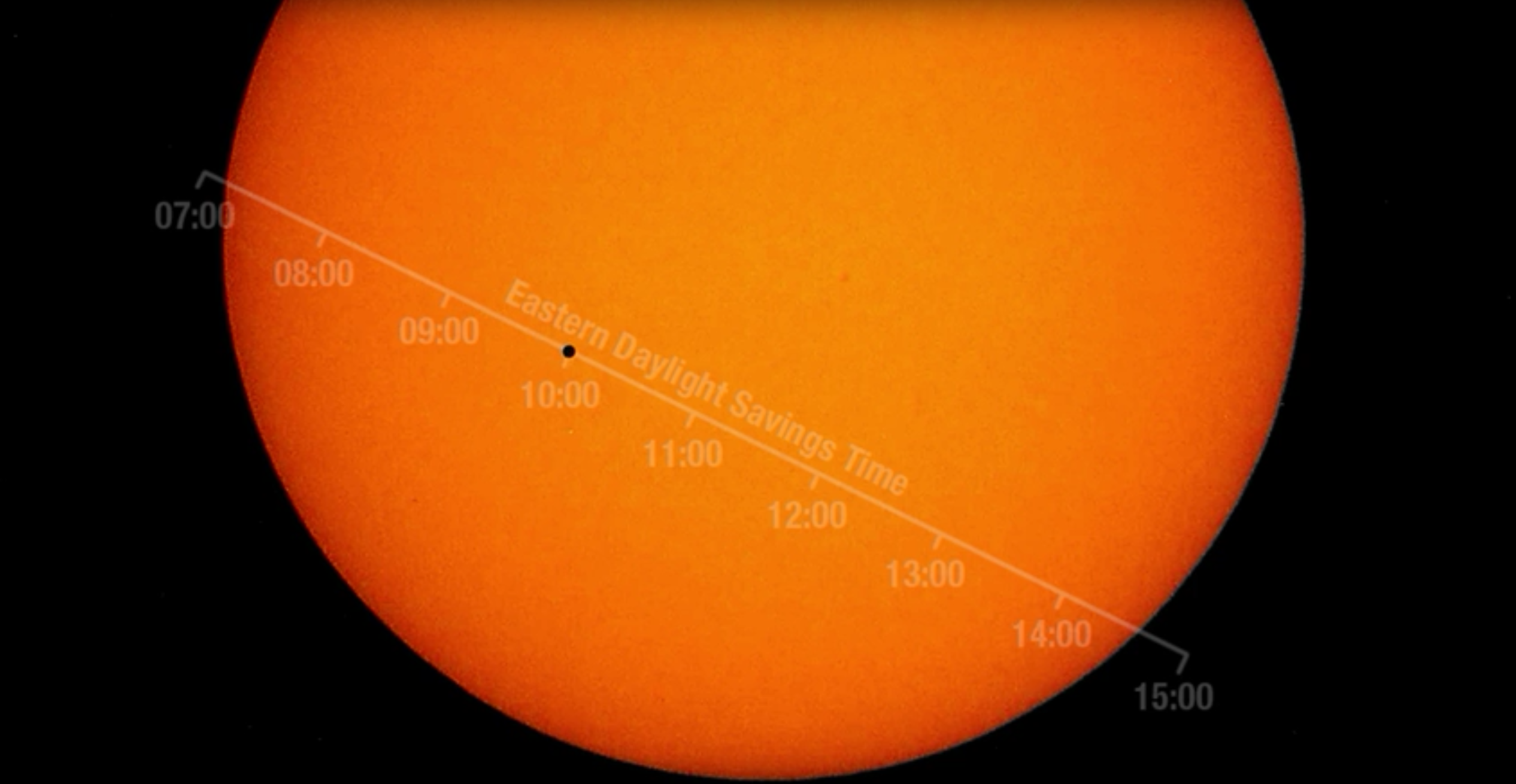

UPDATE - May 9, 2016: NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, spacecraft captured stunning images of the May 9, 2016 transit of Mercury. Visit the mission's Transit of Mercury page to see a collection of videos of the transit compiled using SDO images. And have students play "Can You Spot Mercury?" in our educational slideshow.

In the News

It only happens about 13 times per century and hasn’t happened in nearly a decade, but on Monday, May 9, Mercury will transit the sun. A transit happens when a planet crosses in front of a star. From our perspective on Earth, we only ever see two planets transit the sun: Mercury and Venus. (Transits of Venus are even more rare. The next one won't happen until 2117!) On May 9, as Mercury passes in front of the sun, viewers around Earth (using the proper safety equipment) will be able to see a tiny dark spot moving slowly across the disk of the sun.

CAUTION: Looking directly at the sun can cause permanent vision damage – see below for tips on how to safely view the transit.

Why It's Important

Then and Now

In the early 1600s, Johannes Kepler discovered that both Mercury and Venus would transit the sun in 1631. It was fortunate timing: The telescope had been invented just 23 years earlier and the transits wouldn’t happen in the same year again until 13425. Kepler didn’t survive to see the transits, but French astronomer Pierre Gassendi became the first person to see the transit of Mercury (the transit of Venus wasn’t visible from Europe). It was soon understood that transits could be used as an opportunity to measure the apparent diameter – how large a planet appears from Earth – with great accuracy.

In 1677, Edmond Halley observed the transit of Mercury and realized that the parallax shift of the planet – the variation in Mercury’s apparent position against the disk of the sun as seen by observers at distant points on Earth – could be used to accurately measure the distance between the sun and Earth, which wasn’t known at the time.

Today, radar is used to measure the distance between Earth and the sun with greater precision than can be found using transit observations, but the transit of Mercury still provides scientists with opportunities for scientific investigation in two important areas: exospheres and exoplanets.

Exosphere Science

Some objects, like the moon and Mercury, were originally thought to have no atmosphere. But scientists have discovered that these bodies are actually surrounded in an ultra-thin atmosphere of gases called an exosphere. Scientists want to better understand the composition and density of the gases that make up Mercury’s exosphere and transits make that possible.

“When Mercury is in front of the sun, we can study the exosphere close to the planet,” said NASA scientist Rosemary Killen. “Sodium in the exosphere absorbs and re-emits a yellow-orange color from sunlight, and by measuring that absorption, we can learn about the density of gas there.”

Exoplanet Discoveries

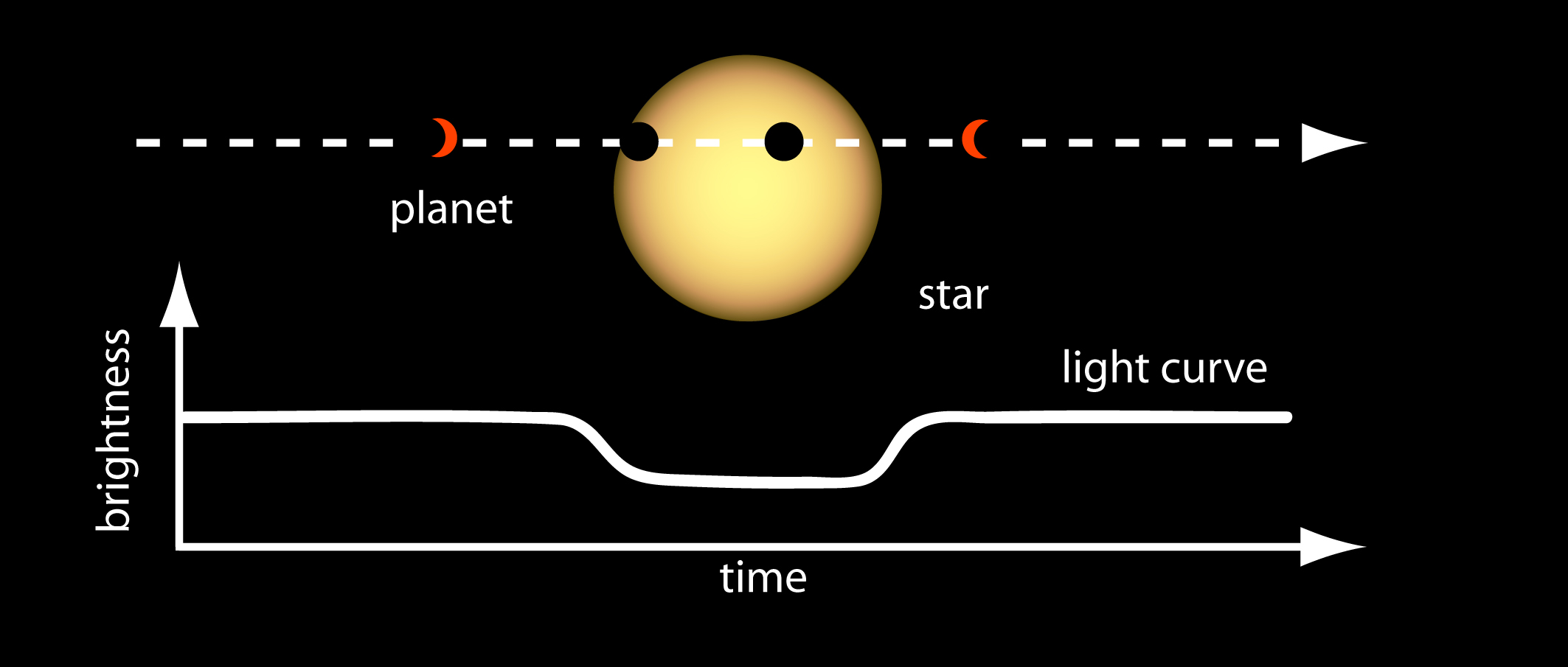

When Mercury transits the sun, it causes a slight dip in the sun’s brightness as it blocks a tiny portion of the sun's light. Scientists discovered they could use that phenomenon to search for planets orbiting distant stars, called exoplanets, that are otherwise obscured from view by the light of the star. When measuring the brightness of far-off stars, a slight recurring dip in the light curve (a graph of light intensity) could indicate an exoplanet orbiting and transiting its star. NASA’s Kepler mission has found more than 1,000 exoplanets by looking for this telltale drop in brightness.

Additionally, scientists have begun exploring the exospheres of exoplanets. By observing the spectra of the light that passes through an exosphere – similar to how we study Mercury’s exosphere – scientists are beginning to understand the evolution of exoplanet atmospheres as well as the influence of stellar wind and magnetic fields.

Watch It

Mercury will appear as a tiny dot on the sun’s surface and will require a telescope or binoculars with a special solar filter to see. Looking at the sun directly or through a telescope without proper protection can lead to serious and permanent vision damage. Do not look directly at the sun without a solar filter.

The transit of Mercury will begin at 4:12 a.m. PDT, meaning by the time the sun rises on the West Coast, Mercury will have been transiting the sun for nearly two hours. Fortunately, it will take seven and a half hours for Mercury to completely cross the sun’s face, so there will be plenty of time for West Coast viewers to witness this event. See the transit map to learn when and where the transit will be visible.

Don’t have access to a telescope, binoculars or a solar filter? Visit the Night Sky Network website for the location of events near you where amateur astronomers will have viewing opportunities available.

NASA also will stream a live program on NASA TV and the agency’s Facebook page from 7:30 to 8:30 a.m. PDT (10:30 to 11:30 a.m. EDT) -- an informal roundtable during which experts representing planetary, heliophysics and astrophysics will discuss the science behind the Mercury transit. Viewers can ask questions via Facebook and Twitter using #AskNASA.

Teach It

Here are two ways to turn the transit of Mercury into a lesson for students.

- Exploring Exoplanets with Kepler - Students use math concepts related to transits to discover real-world data about Mercury, Venus and planets outside our solar system.

- Pi in the Sky 3 - Try the "Sun Screen" problem on this illustrated math problem set that has students calculate the percentage drop in sunlight reaching Earth when Mercury transits.

Explore More

Transit Resources:

- NASA TV (live transit coverage)

- NASA Transit Website (near real-time images of the transit)

- Night Sky Network Events

- Video: What’s Up – May 2016

- Transit Map

- Solar System Transits

- NASA Museum Alliance Resources

Exoplanet Resources:

- Kepler Mission Website

- Exoplanet Exploration Website

- Eyes on Exoplanets Interactive

- Exoplanet Travel Bureau Posters

- Video: What’s in an Exoplanet Name?

- Video: The Search for Another Earth

- Kepler Education Activities

TAGS: Transit, Transit of Mercury, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Exoplanets, Teach, Classroom Activities, Lessons,