Clouds in the Northern Tempe Terra

Jet Propulsion Laboratory https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/ May 23, 2002

(Released 2 May 2002)

The Science

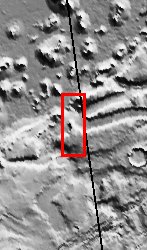

This THEMIS visible image shows a region in northern Tempe Terra near 48° N, 75° W (285° E). Patchy water-ice clouds cover portions of the low-lying canyon at the top (north) of this image. Further south the atmosphere is clear and the knobby or "scabby" plains that are typical of many mid-latitude regions on Mars can be seen. These plains appear to mantle and modify a pre-existing surface, burying the older cratered terrain. This mantling layer has itself been modified to produce a pitted, knobby surface. The large mesa seen in this image has unusual deposits of material that occur preferentially on the cold, north-facing slopes. These deposits are seen frequently at mid-northern and southern latitudes, and have a distinct, rounded boundary that typically occurs at approximately the same distance below the ridge crest. It has been suggested that these deposits once draped the entire surface and have since been removed from all but the north-facing slopes. The presence of water ice in these layers is a likely possibility to account for their preservation only on the colder surfaces. The south-facing slopes lack this mantling material, and show clear evidence for layering in the rock units that form the mesa.

The Story

This deep and murky-looking depression is in an area called "Tempe Terra," a lilting, alliterative name that seems almost a little too merry for this kind of terrain.

If the top of the image looks a little smudgy, that's because patchy water-ice clouds hang over the low lying canyon. Further south, where the air is clear, you can see some "scabby" plains (particularly in the high-res image, where the knobby patches of raised surface areas sort of do look like crusted-over dirt wounds). These plains cover a more ancient, cratered surface, but have been eroded away enough to form these scabby-seeming features.

The large mesa in this image has some odd deposits of material on its cold, north-facing slopes. Could these deposits have been all over the surface of Mars long ago, but then were subsequently eroded away in most places on the planet? Did water ice on the colder surfaces preserve the last vestiges of these deposits so that scientists have the advantage of studying them today?

While those answers won't be clear for a while, the south-facing slopes don't have this piled on material. That makes it easier to see the rock layers in the mesa. Layers are important to study, because they tell what has happened to the planet geologically over its history. The bottom layers are usually the oldest (unless some geologic force has pushed them up), so looking at each layer can give an idea of what happened first and last . . . and maybe even how long each period of time lasted.