The So-Called "Face on Mars"

(Released 13 April 2002)

The Science

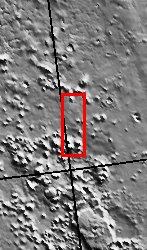

The so called "Face on Mars" can be seen slightly above center and to the right in this THEMIS visible image. This 3-km long knob, located near 10° N, 40° W (320° E), was first imaged by the Viking spacecraft in the 1970's and was seen by some to resemble a face carved into the rocks of Mars. Since that time the Mars Orbiter Camera on the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft has provided detailed views of this hill that clearly show that it is a normal geologic feature with slopes and ridges carved by eons of wind and downslope motion due to gravity. A similar-size hill in Phoenix, Arizona resembles a camel lying on the ground, and Phoenicians whimsically refer to it as Camelback Mountain. Like the hills and knobs of Mars, however, Camelback Mountain was carved into its unusual shape by thousands of years of erosion. The THEMIS image provides a broad perspective of the landscape in this region, showing numerous knobs and hills that have been eroded into a remarkable array of different shapes. Many of these knobs, including the "Face," have several flat ledges partway up the hill slopes. These ledges are made of more resistant layers of rock and are the last remnants of layers that once were continuous across this entire region. Erosion has completely removed these layers in most places, leaving behind only the small isolated hills and knobs seen today.

Many of the hills and ridges in this area also show unusual deposits of material that occur preferentially on the cold, north-facing slopes. It has been suggested that these deposits were "pasted" on the slopes, with the distinct, rounded boundary on their upslope edges being the highest remaining point of this pasted-on layer. In several locations, such as in the large knob directly south of the "Face," these deposits occur at several different heights on the hill. This observation suggests the layer once draped the entire knob and has since been removed from all but the north-facing slopes. The presence of water ice in these layers is a likely possibility to account for their preservation only on the colder surfaces. Alternatively, these unique features could be the result of the slow downslope motion of the surface layer, possibly enhanced by the presence of ground ice. One argument against downslope motion is the observation that the uppermost rounded boundary of these layers typically occurs at approximately the same distance below the ridge crest. This would suggest the (seemingly) unlikely possibility that all of these layers had moved downslope the same amount regardless of where they are located. In either case, ground ice likely plays an important role in the formation and preservation of these deposits because they only occur on the cold slopes facing away from the Sun where ground ice is more stable and may still be present today.

The Story

Nature is an imaginative artist, creating all kinds of wonderful landforms, cloud shapes, and other patterned features that remind people of familiar things in our lives. We see a "man in the moon" when it is full in the night sky, and dream of a dromedary-dotted desert when coming upon Arizona's Camelback Mountain or Colorado's "Kissing Camels" in the "Garden of the Gods." Near Ludlow, California, a lonely prospector once noticed that the appealing outline of the mountains resembled a reclining woman, and named the place Sleeping Beauty. And this naming delight isn't limited to Earth. The Mars Pathfinder mission team couldn't help but name the rocks at the landing site, including a bear-headed-looking one named Yogi.

Part of the fun of exploration is not just visiting a strange world, but relating to it in human terms. On Mars, we've already seen a valentine heart-shaped crater, a happy-faced crater, and even a murky and mysterious "face" on Mars. This face (seen here about halfway down the image and to the right) is really just a hill with slopes and ridges that are shadowed in a way that can sometimes resemble a face from far away. The first picture of this area was taken by the Viking spacecraft in the 1970s, and people have been intrigued ever since. However, orbiter camera technologies have actually become so good in providing a clear view of the hill that it's almost a disappointment to see how normal an eroded hill this well-liked feature is. Well, disappointing unless you're a geologist, that is!

This whole area is, in fact, a geologist's dream. Erosion has been Nature's sculptor throughout the area, and all kinds of remarkably shaped knobs and hills speckle the region. While their shapes are fun to contemplate, it's no mystery to geologists how they formed. Several flat ledges part way up the slopes of these hills are made of layers of rock that stand strong against erosion's relentless carving. Less resistant layers in the region have eroded away completely in most places, leaving behind only the small, isolated hills and knobs we see today. Don?t think everything in this scene is easily understandable, however. What captures the attention of scientists is a bunch of unusual deposits of material on the cold, north-facing slopes of the hills. Did Nature mix some Martian dirt and ice from the planet's "pallet," and then "paste" on a slightly cemented deposit over the northern slopes? Or did an upper layer of material slowly creep downslope over time, carried by the movement of ice? Ground ice, in this case, has probably been more of a preserver than an eroder, keeping a record of the formation and existence of these deposits over time. Geologists are grateful for that peek into the Martian past and the chance to study it in-depth.