Dawn Journal | August 22, 2018

Dear Sinceres Readers,

People have been gazing in wonder and appreciation at the beauty of the night sky throughout the history of our species. The gleaming jewels in the seemingly infinite black of space ignite passions and stir myriad thoughts and feelings, from the trivial to the profound. Many people have been inspired to learn more, sometimes even devoting their lives to the pursuit of new knowledge. Since Galileo pointed his telescope up four centuries ago and beheld astonishing new sights, more and more celestial gems have been discovered, making us ever richer.

In a practical sense, Dawn brought two of those jewels down to Earth, or at least brought them more securely within the scope of Earthlings' knowledge. Science and technology together have uncloaked and explained aspects of the universe that would otherwise have seemed entirely inscrutable. Vesta and Ceres revealed little of themselves as they were observed with telescopes for more than two centuries. Throughout that time, they beckoned, waiting for a visitor from distant Earth. Finally their cosmic invitations were answered when Dawn arrived to introduce each of them to Earth, whereupon the two planet-like worlds gave up many of their secrets.

Even now, Ceres continues to do so, as it holds Dawn in its firm but gentle gravitational embrace. Every 27 hours, almost once a day, the orbiting explorer plunges from 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) high to as low as about 22 miles (35 kilometers) and then shoots back up again. Each time Dawn races over the alien landscapes, it gathers information to add to the detailed story it has been compiling on the dwarf planet.

Dawn began its ambitious mission in 2007. (And on Aug. 17, 2018, it passed a milestone: three Vestan years of being in space.) But the mission is rapidly approaching its conclusion. In the previous Dawn Journal, we began an in-depth discussion of the end, and we continue it here.

We described how the spacecraft will lose the ability to control its orientation, perhaps as soon as September. It will struggle for a short time, but it will be impotent. Unable to point its electricity-generating solar panels at the Sun or its radio antenna to Earth, the seasoned explorer will go silent and will explore no more. Its expedition will be over.

We also took a short look at the long-term fate of the spacecraft. To ensure the integrity of possible future exploration that may focus on the chemistry related to life, planetary protection protocols dictate that Dawn not contact Ceres for at least 20 years. Despite being in an orbit that regularly dips so low, the spaceship will continue to revolve around its gravitational master for at least that long and, with very high confidence, for more than 50 years. The terrestrial materials that compose the probe will not contaminate the alien world before another Earth ship could arrive.

Like its human colleagues, Dawn started out on Earth, but now its permanent residence in the solar system, Ceres, is far, far away. Let's bring this cosmic landscape into perspective.

Imagine Earth reduced to the size of a soccer ball. On this scale, the International Space Station would orbit at an altitude of a bit more than one-quarter of an inch (7 millimeters). The moon would be a billiard ball almost 21 feet (6.4 meters) away. The Sun, the conductor of the solar system orchestra, would be 79 feet (24 meters) across at a distance of 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers). More remote even than that, when Dawn ceases operating, it would be more than 5.5 miles (9.0 kilometers) from the soccer ball. The ship will stay locked in orbit around Ceres, the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system. The largest object between Mars and Jupiter, that distant orb would be five-eighths of an inch (1.6 centimeters) across, about the size of a grape. Of course, a grape has a higher water content than Ceres, but exploring this fascinating world of ice, rock and salt has been so much sweeter!

Now let's take a less terrestrial viewpoint and shift our reference to Ceres. Suppose it were the size of a soccer ball. In Dawn's final, elliptical orbit, which it entered in June, the spacecraft would travel only 37 inches (94 centimeters) away at its farthest point. Then it would go in to skim a mere one-third of an inch (8 millimeters) from the ball.

Dawn is one mission among many to explore the solar system, dating back almost 60 years and (we hope) continuing and even accelerating for much longer into the future. Learning about the cosmos is not a competition but rather a collective effort of humankind to advance our understanding. And to clarify one of the many popular mistaken notions about the solar system, let's take advantage of reducing Ceres to the size of a soccer ball to put some other bodies in perspective.

Because it is in the main asteroid belt, there is a common misconception that Ceres is just another asteroid, somehow like the ones visited by other spacecraft. It is not. The dwarf planet is distinctly unlike the small chunks of rock that are more typical asteroids. We have discussed various aspects of Ceres' complex geology, and much more remains to be gleaned from Dawn's data. Vesta too has a rich and complicated geology, and it is more akin to the terrestrial planets (including Earth) than to asteroids. But for now, let's focus simply on the size in order to make for an easy comparison. Of course, size is not a measure of interest or importance, but it will illustrate how dramatically different these objects are.

With a soccer-ball-sized Ceres, Vesta would be nearly five inches (more than 12 centimeters) in diameter. (This writer's comprehensive knowledge of sports inspires him to describe this as a ball nearly five inches, or more than 12 centimeters, in diameter.)

What about some of the asteroids being explored as Dawn's mission winds to an end? There are two wonderfully exciting missions with major events at asteroids (albeit ones much closer to Earth than the main asteroid belt) in the second half of 2018. Your correspondent, a lifelong space enthusiast, is as hopeful for success as anyone! Hayabusa2 is revealing Ryugu and OSIRIS-REx is on the verge of unveiling Bennu.

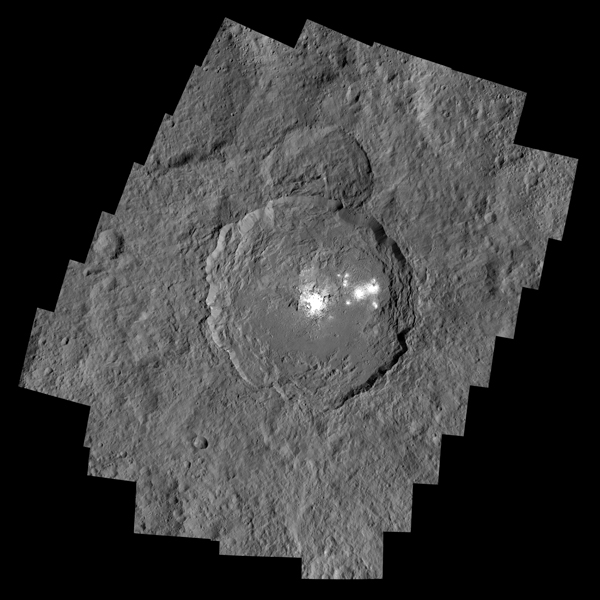

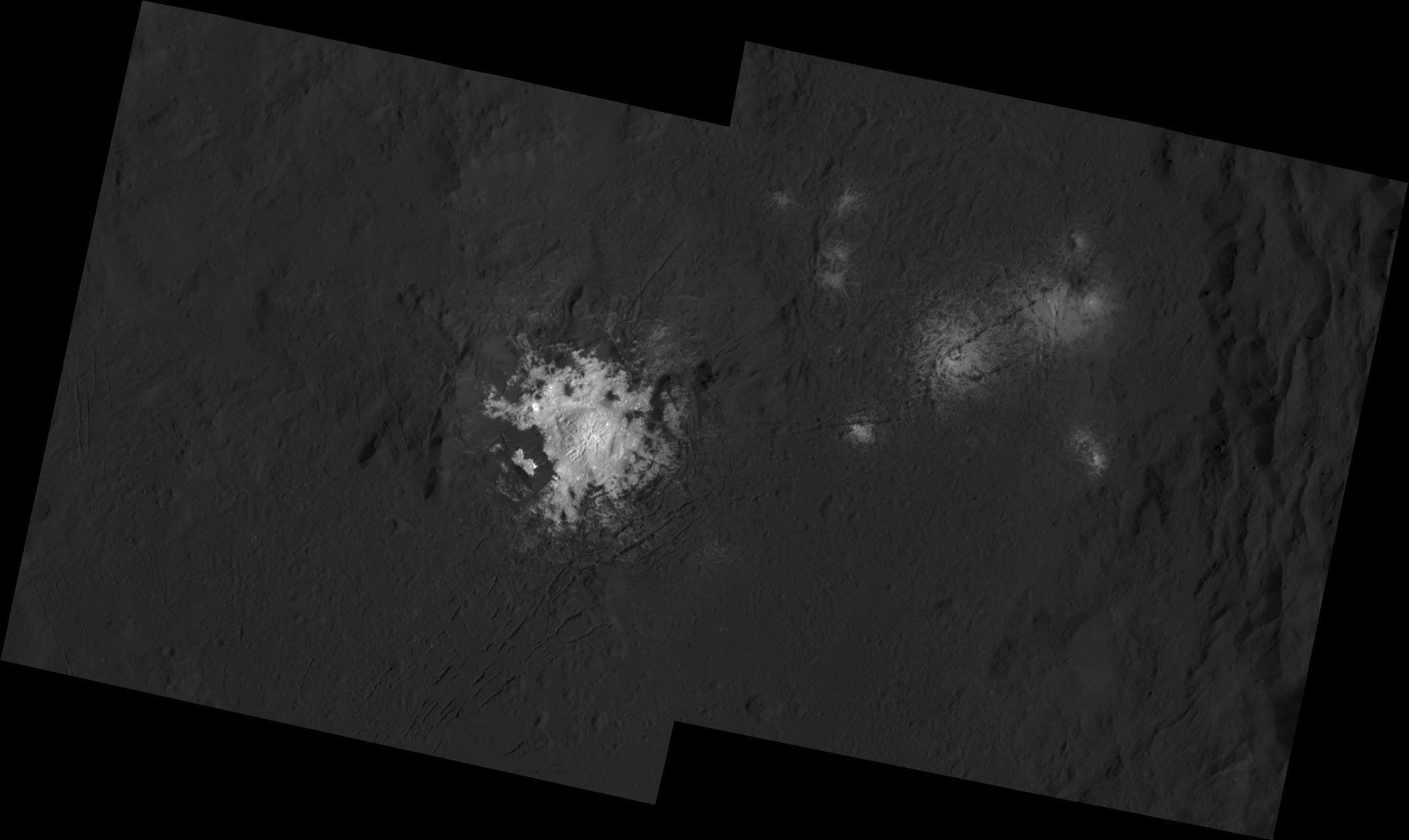

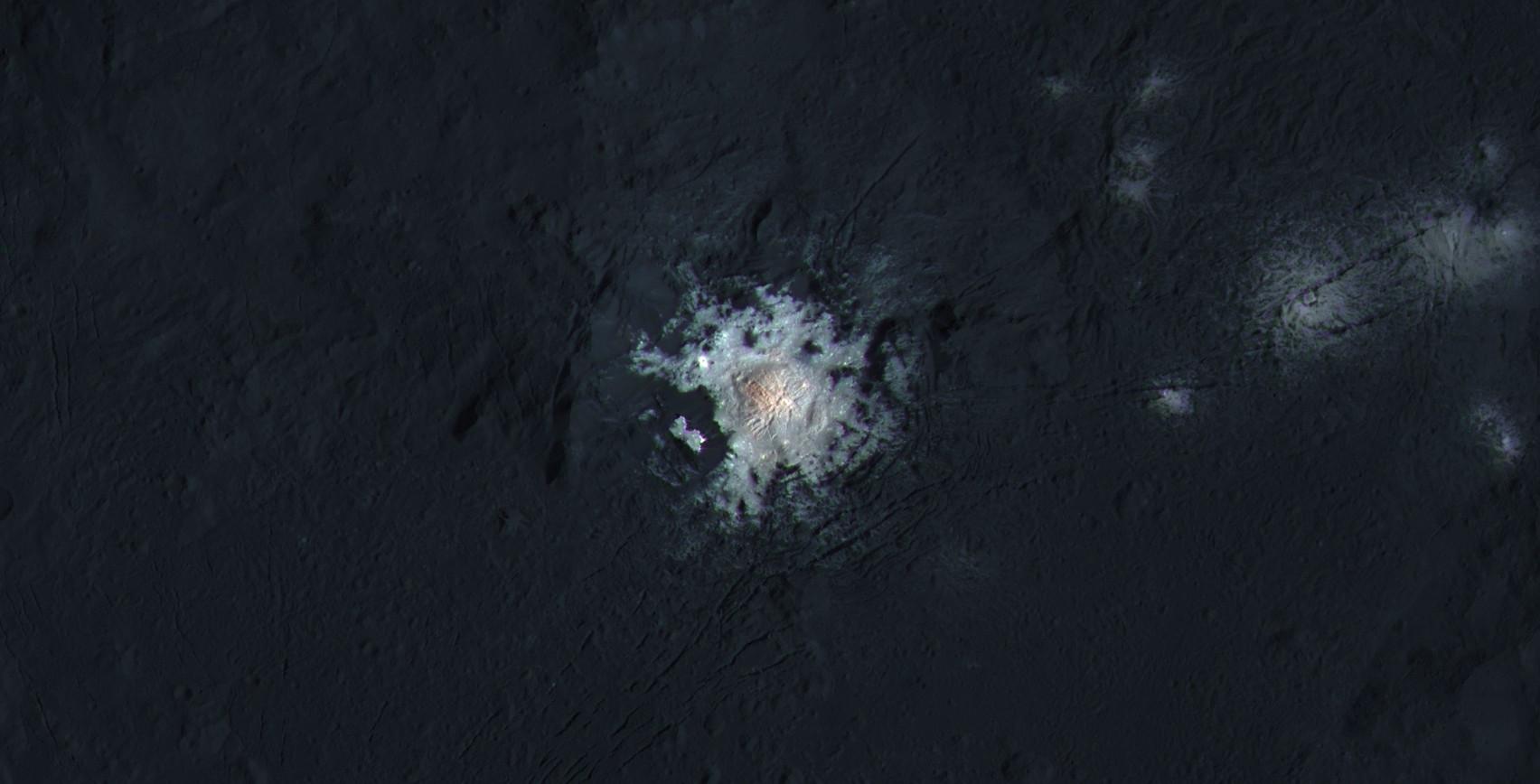

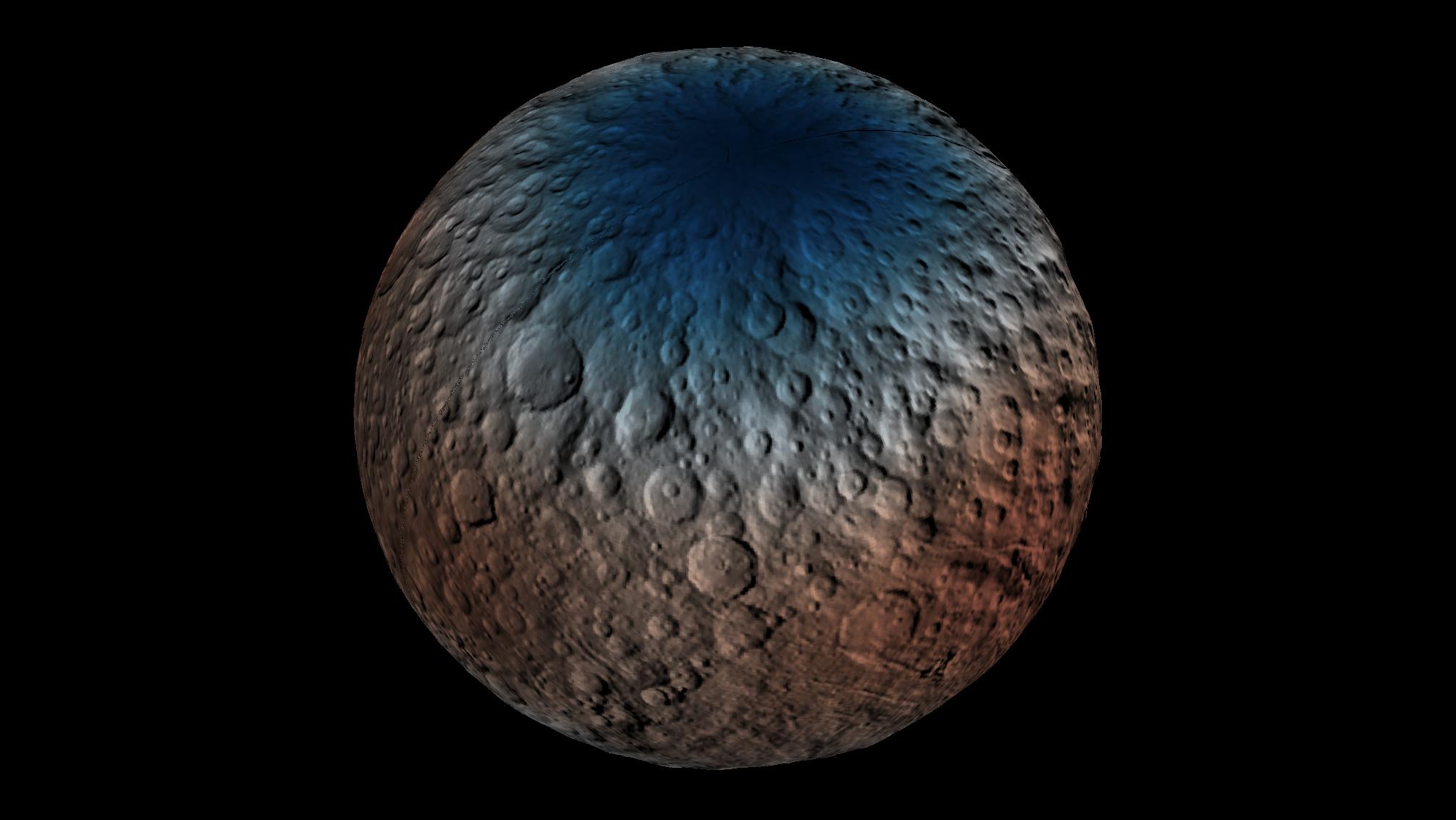

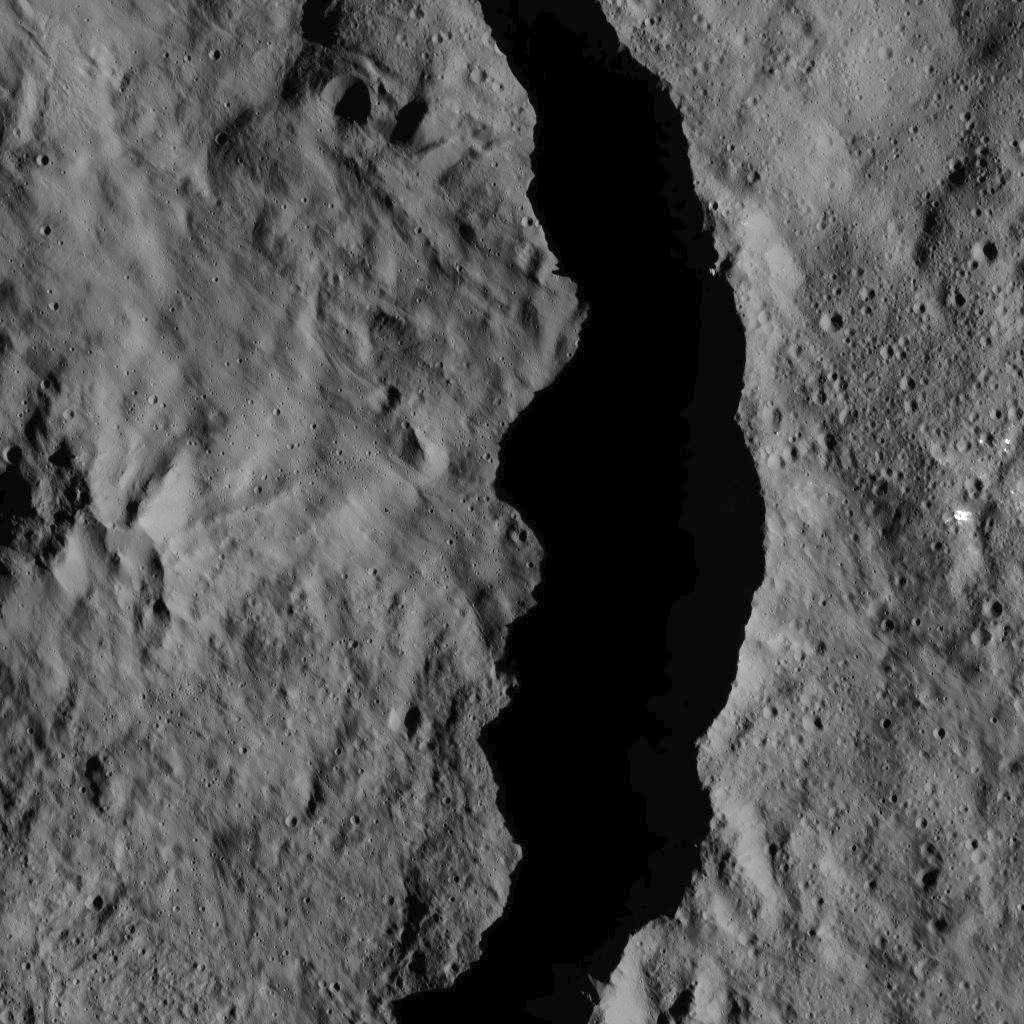

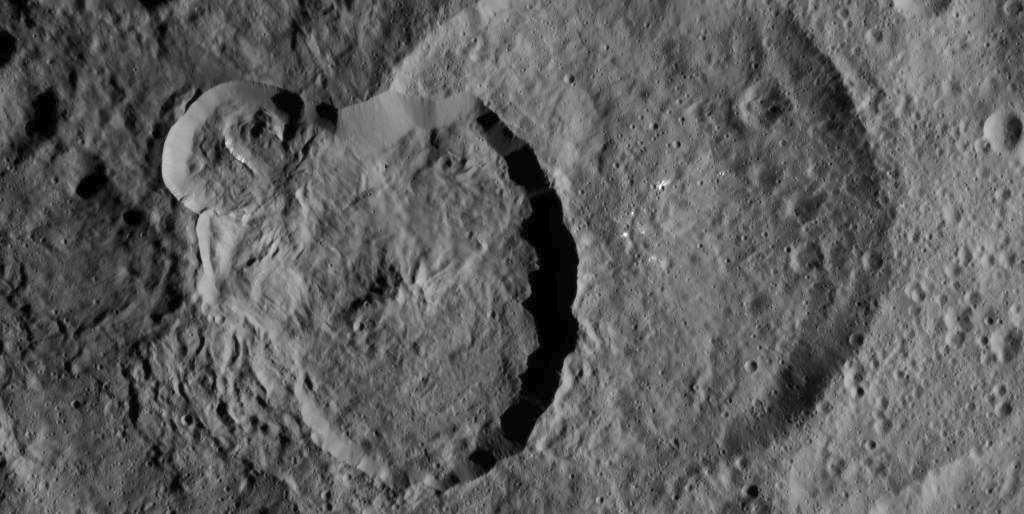

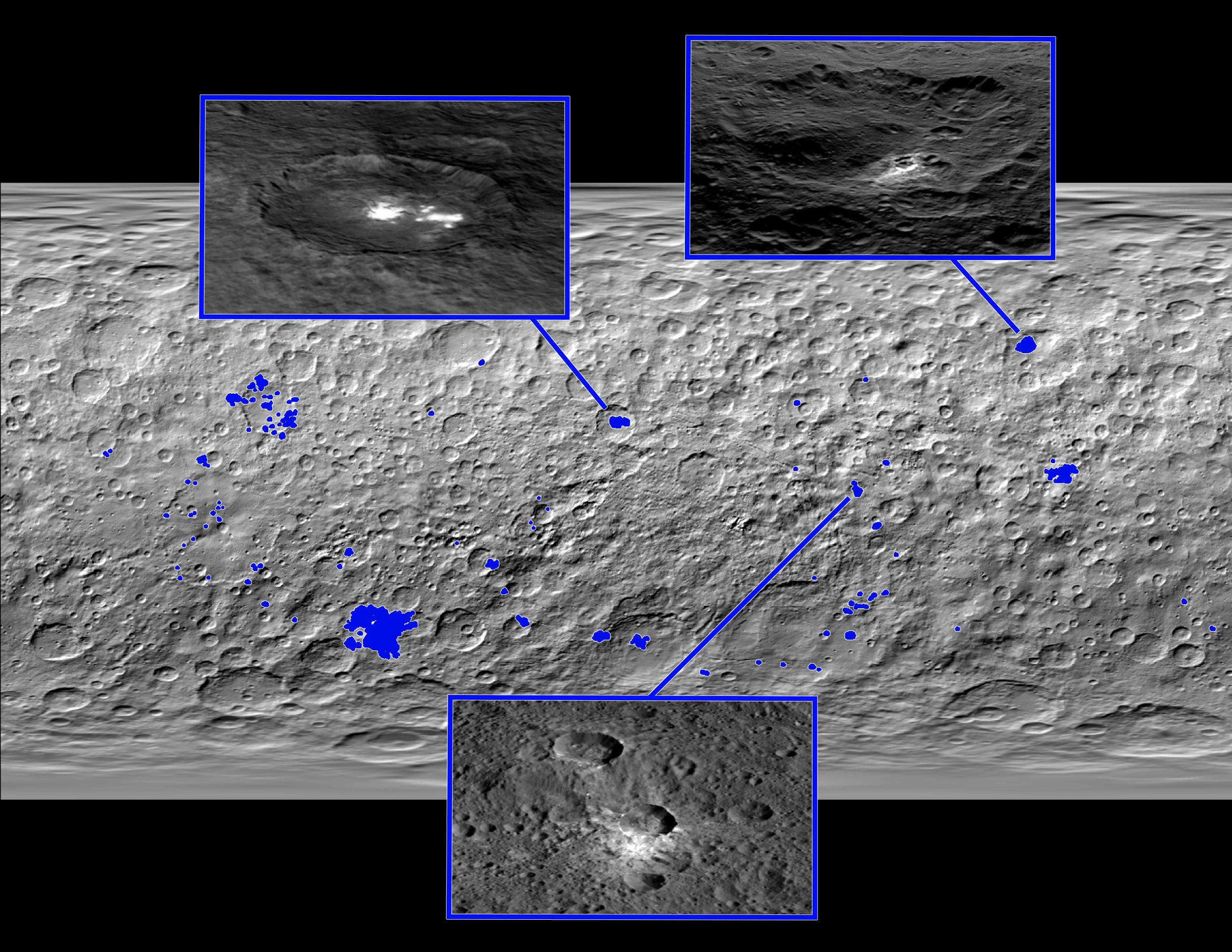

Ryugu and Bennu are more irregular in shape than Ceres and Vesta, but they would both be so small compared to the soccer ball that their specific shapes wouldn't matter. Ryugu would be less than a hundredth of an inch (a quarter of a millimeter) across. Bennu would be about half that size. They would be like two grains of sand compared to the soccer ball. In the first picture of the June Dawn Journal, we remarked on the detail visible in a feature photographed on one of Dawn's low streaks over the alien terrain. It is also visible in the first two pictures above. That one structure on Ceres is only a part of Cerealia Facula, which is the bright center of the much larger Occator Crater. Occator is a good-sized crater, but not even among the 10 largest on Ceres. Yet that one bright feature in the high-resolution photo is larger than either of these small asteroids. In many of Dawn's pictures that show the entire disk of the dwarf planet (like the rotation movie and the color picture here), Ryugu and Bennu would be less than a pixel, undetectably small, just as invisible specks of dust on a soccer ball.

The tremendous difference in size between Ceres (and Vesta) and small asteroids illustrates a widely unappreciated diversity in the solar system. Of course, that is part of the motivation for continuing to explore. There is a great deal yet to be learned!

Although Ryugu and Bennu aren't in the main asteroid belt, the belt contains many more Lilliputian asteroids closer in size to them than to the Brobdingnagian Ceres and Vesta. In fact, of the millions of objects in the main asteroid belt, Ceres by itself contains 35 percent of the total mass. Vesta has 10 percent of the total.

Readers with perfect memories may note that we used slightly smaller fractions in earlier Dawn Journals. Science advances! More recent estimates of the mass of the asteroid belt are slightly lower, so these percentages are now correspondingly higher. The difference is not significant, but the small increase only emphasizes how different Vesta and Ceres are from typical residents of the asteroid belt. It's also noteworthy -- or, at least, pretty cool -- that Dawn has single-handedly explored 45 percent of the mass between Mars and Jupiter.

Dawn will end its mission in the same orbit it is in now, looping around from a fraction of an inch (fraction of a centimeter) to a yard (a meter) from the soccer-ball-sized Ceres. In the previous Dawn Journal, we described what will happen onboard the spacecraft. We also saw that the most likely indication controllers will have that Dawn has run out of hydrazine will be its radio silence. They will take some carefully considered steps to verify that that is the correct conclusion.

But it is certain that emotions will be ahead of rationality. Even as team members are narrowing down the causes for the disappearance of the radio signal, many strong feelings about the end of the mission will arise. And they will be as varied as the people on the Dawn team, every one of whom has worked long and hard to make the mission so successful. Your correspondent can make reasonable guesses about their feelings but won't be so presumptuous as to do so.

As for my own feelings, well, I won't know until it happens, but I'm not too presumptuous to guess now. Long-time readers may recognize that your correspondent has avoided writing anything about himself (with a few rare exceptions), or even using first person, in his Dawn Journals. They are meant to be a record of a mission undertaken by humankind, for everyone who longs for knowledge and for adventures in the cosmos. But now I will devote a few words to my own perspective.

My love affair with the universe began when I was four, and my passion has burned brighter and brighter ever since. I knew when I was a starry-eyed nine-year-old that I wanted to get a Ph.D. in physics and work for NASA, although it was a few more years before I did. I had my own Galileo moment of discovery and awe when I first turned a telescope to the sky. Science and space exploration are part of me. They make me who I am. (My friend Mat Kaplan at The Planetary Society described me in the beginning of this video as "the ultimate space nerd." He's too kind!) Adding to my own understanding and contributing to humankind's knowledge are among my greatest rewards.

Passion and dedication are not the whole story. I recognize how incredibly lucky I am to be doing what I have loved for so long. I am lucky to have had access to the resources I have needed. I am lucky that I was able to do well in my formal education and in my own informal (but extensive) studies. I am lucky I could find the discipline and motivation within myself. For that matter, I am lucky to be able to communicate in terms that appeal to you, dear readers (or, at least, to some of you). My innate abilities and capabilities, and even many acquired ones, are, to a large extent, the product of factors out of my control, like my cognitive and psychological constitution.

That luck has paid off throughout my time at JPL. Working there has been a dream come true for me. It is so cool! I often have what amount to out-of-body experiences. When I am discussing a scientific or engineering point, or when I am explaining a conclusion or decision, sometimes a part of me pulls back and looks at the whole scene. Gosh! Listen to the cool things I get to say! Look at the cool things I get to do! Look at the cool things I know and understand! Imagine the cool spacecraft I'm working with and the cool world it is orbiting! I am still that starry-eyed kid, yet somehow, through luck and coincidence, I am doing the kind of things I love and once could only have dreamed of.

Dawn will continue to be exciting to the very end, performing new and valuable observations as it skims incredibly low over the dwarf planet on every orbital revolution. The spacecraft has almost always either been collecting new data or, thanks to the amazing ion propulsion, flying on a blue beam of xenon ions to somewhere else to gain a new perspective, see new sights and make more discoveries. Whether in orbit around Vesta or Ceres or traveling through the solar system between worlds, the mission was rarely anything like routine.

I love working on Dawn (although it was not my first space love). You won't be surprised that I think it is really cool. I could not be happier with its successes. I am not sad it is ending. I am thrilled beyond belief that it achieved so much!

I was very saddened in graduate school when my grandfather died. When I said something about it in my lab to a scientist from Shanghai I was working with, he asked how old my grandfather was. When I said he was 85, the wiser gentleman's smile lit up and he said, "Oh, you should be happy." And immediately I was! Of course I should be happy -- my grandfather had lived a long (and happy) life.

And so has Dawn. It has overcome problems not even imagined when we were designing and building it. It not only exceeded all of its original goals, but it has accomplished ambitious objectives not even conceived of until after it had experienced what could have been mission-ending failures. It has carried me, and uncounted others (including, I hope, you), on a truly amazing and exciting deep-space adventure with spectacular discoveries. Dawn is an extraordinary success by any measure.

It did not come easily. Dawn has consumed a tremendous amount of my life energy, many times at the expense of other desires and interests. (Perhaps ironically, it even comes at the expense of my many other deep interests in space exploration and in science, such as cosmology and particle physics, interests shared by my cats Quark and Lepton. Also, writing these Dawn Journals and doing my other outreach activities take up a very large fraction of what would otherwise be my personal time. As a result, I always write these in haste, and I'm never satisfied with them. That applies to this one as well. But I must rush ahead.) The challenges and the demands have been enormous, sometimes feeling insurmountable. That would not have been my preference, of course, yet it makes the endeavor's successful outcome that much more gratifying.

At the same time I have felt all the pressure, I have long been so overjoyed with the nature of the mission, I will miss it. There is nothing quite like controlling a spacecraft well over a thousand times farther than the Moon, farther even than the Sun. Silly, trite, perhaps even mawkish though it may seem, when spacecraft I have been responsible for have passed on the far side of the Sun, I have taken those opportunities to use that blinding signpost to experience some of the awe of the missions. I block the Sun with my hand and contemplate the significance, both to this particular big, starry-eyed kid and to humankind, of such an alignment. I -- we -- have a spacecraft on the far side of the Sun!

Every day I feel exhilarated knowing that, as my car's license plate frame proclaims, my other vehicle is in the main asteroid belt. It won't be the same when that vehicle is no longer operating.

But I will always have the memories, the thrills, the deep and powerful personal gratification. And I have good reason to believe they will persist, just as some prior space experiences still fill me with gratitude, pride, excitement and pure joy. (I also hope to have many more cool out-of-body experiences.)

And long after I'm gone and forgotten, Dawn’s successes will still be important. Its place in the annals of space exploration will be secure: a wealth of marvelous scientific discoveries, the first spacecraft to orbit an object in the asteroid belt, the first spacecraft to visit a dwarf planet (indeed, the first spacecraft to visit the first dwarf planet that was discovered), the first spacecraft to orbit a dwarf planet, the first spacecraft to orbit any two extraterrestrial destinations, and more.

For now, Dawn is continuing to operate beautifully (and you can read about it in subsequent Dawn Journals). The end of the mission, when it comes, will be bittersweet for me, a time to reflect and rejoice at how fantastically well it has gone, and a time to grieve that it is no more. I will have many powerful and conflicting feelings. Like Walt Whitman, I am large, I contain multitudes.

Thanks to Dawn, we now have Vesta and we now have Ceres. Soon, very soon, Dawn will be only a memory (save for those who visit Ceres and find it still in orbit) but the worlds it revealed will forever be a part of our intellectual universe, and the capabilities to explore the solar system that it advanced and devised will be applied to exciting new missions. And the experience of being intimately involved in this grand adventure will remain with me for as long as I am able to see the night sky and marvel at the mysteries of the universe that captivated me even as a starry-eyed child.

Dawn is 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 3.46 AU (322 million miles, or 518 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,275 times as far as the Moon and 3.42 times as far as the Sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 58 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

10:00 pm PDT August 22, 2018

TAGS: DAWN, CERES, VESTA, DWARF PLANET, ASTEROID BELT, ASTEROIDS, SPACECRAFT, SOLAR SYSTEM

Dawn Journal | August 21, 2018

Dear Dawnouements,

A fantastic story of adventure, exploration and discovery is reaching its denouement. In the final phase of its long and productive deep-space mission, Dawn is operating flawlessly in orbit around dwarf planet Ceres.

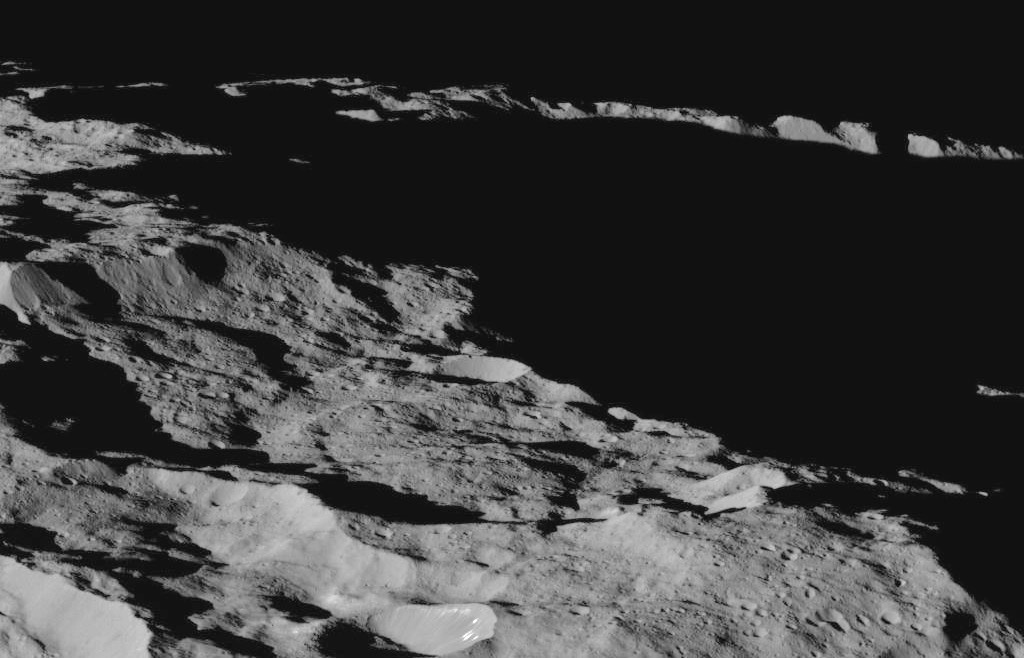

As described in the previous Dawn Journal, every 27 hours the spacecraft swoops as low as about 22 miles (35 kilometers) above the ground, taking stunning pictures and making other unique, valuable measurements with its suite of sophisticated sensors. It then soars up to 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) over the alien world before diving down again.

While it is too soon to reach clear conclusions from the wealth of high-resolution data, some of the questions already raised are noteworthy: Are the new pictures totally awesome or are they insane? Are they incredible or are they unbelievable? Are they amazing or are they spectacular? It may take years to resolve such questions. The mission will end long before then, indeed very soon. In this Dawn Journal and the next one (which will be posted in about three Cerean days), we will preview the end.

When Dawn left Earth in 2007, it was outfitted with four reaction wheels, devices that were considered indispensable for controlling its orientation on its long expedition in deep space. Despite the failures of reaction wheels in 2010, 2012 and 2017, the team has accomplished an extremely successful mission, yielding riches at Vesta and at Ceres far beyond what had been anticipated when the interplanetary journey began. But now the rapidly dwindling supply of hydrazine propellant the robot uses in place of the reaction wheels is nearly exhausted.

With no friction to stabilize it, the large ship, with electricity-generating solar arrays stretching 65 feet (19.7 meters) wingtip-to-wingtip, holds its orientation in space by firing hydrazine propellant from the small jets of its reaction control system. The orientation should not be confused with the position. In the zero-gravity of spaceflight, they are quite independent. Unlike an aircraft, a spacecraft's position and the direction it travels are largely unrelated to its orientation. The probe's position is dictated by the principles of orbital motion, whether in orbit around the Sun, Vesta or (now) Ceres, and the ion propulsion system is used to change its trajectory. We are concerned here about orientation.

Dawn can hold its orientation quite stable, but it still lazily oscillates a little bit in pitch, roll and yaw. When the spacecraft points its main antenna to Earth, for example, spending many hours radioing its findings to the Deep Space Network (DSN) as it travels around Ceres, it rotates back and forth, but the angular motion is both tiny and slow. The ship turns about a thousand times slower than the hour hand on a clock. The clock hand continues its steady motion, going all the way around, rotating through a full circle in 12 hours. Dawn needs to keep its antenna pointed at Earth, however. If Dawn were at the center of the clock and Earth were at the 12, it wouldn't let the antenna point any farther away than the hour hand gets from the 12 in about a minute. The tiny angle is only about a tenth of the way from the 12 to the adjacent ticks (both on the left and on the right) that mark one second for the second hand. When Dawn's orientation approaches the maximum allowed angular deviation, the main computer instructs a jet to puff out a little hydrazine to reverse the motion.

When the spacecraft follows its elliptical orbit down to a low altitude, only three times higher than you are when you fly on a commercial jet, it needs to expel hydrazine to keep aiming its camera and spectrometers down as it rushes over the ground. If this isn't clear, try pointing your finger at an object and then circling around it. You are constantly changing the direction you're pointing. For Dawn to do that, especially in its elliptical orbit, requires hydrazine. (If you think Dawn could simply start rotating with hydrazine and then just point without using more, there are some subtleties here we will not describe. It really does require extensive hydrazine.)

Whether pointing at the landscape beneath it or at Earth, it might seem that Dawn could remain perfectly steady, but there are always tiny forces acting on it that would compromise its pointing. One is caused by the difference between Ceres' gravitational pull on the two ends of the solar arrays that occurs when the wings are not perfectly level. (We described this gravity gradient torque when Dawn was orbiting Vesta.) Also, sunlight reflecting in different ways from different components (some with polished, mirror-like surfaces, others with matte finishes) can exert a very small torque. Dawn uses hydrazine to counter these and other slight disturbances in its orientation.

As we have discussed extensively, very soon, the hydrazine will be depleted. Most likely between the middle of September and the middle of October (although possibly earlier or later), the computer will tell a reaction control jet to emit a small burst of hydrazine, as it has myriad times before in the mission, but the jet will not be able to do so. There won't be any usable hydrazine left. It will be like opening the end of a completely deflated balloon. No gas will escape. There will be no action, so there will be no reaction. Dawn's very slow angular motion will not be reversed but rather will continue, and the orientation will slowly move out of the tight bounds the ship normally maintains.

The computer will quickly recognize that the intended effect was not achieved. It will send more signals to the jet to fire, but the result will be no different. On a mission often operating out of radio contact with Earth and always very, very far away, help can never be immediate (after all, radio signals travel at the universal limit of the speed of light), so the robot is programmed to deal with problems on its own. There are several possibilities for what actions Dawn will take, depending on details we will not delve into, but a likely one is to try switching from the primary reaction control jets to the backup reaction control jets. Of course, that won't fix the problem, because the jets will not be at fault. In fact, with no hydrazine available, none of its attempts to correct the problem will succeed.

When Dawn experiences problems it can't resolve on its own, it invokes one of its safe modes, standard responses the craft uses when it encounters conditions its programming and logic cannot accommodate. (We have described the safe modes a number of times before, with perhaps the most exciting time being here.) In this case, the safe mode it will chose will go through many steps to reconfigure the spacecraft and prepare to wait for help from humans on a faraway planet (or anyone else who happens to lend assistance).

One of the first steps will be to temporarily power off the radio transmitter, one of the biggest consumers of electrical power on the ship. Until Dawn can make all of the necessary changes, including turning to point the solar panels at the Sun, it will not want to devote precious energy to unnecessary systems. Electrical power is vital. Without it, the spacecraft will be completely inoperative, just as your car, computer, smartphone or lights do nothing at all when they are deprived of power.

Dawn will try to do all its work using only the energy stored in its battery (which it keeps charged, using excess power from the solar arrays). It knows that later, once the arrays are in sunlight, it will have plenty of power, but in the meantime, it needs to be parsimonious. The computer, heaters, motors to rotate the solar arrays, and some other devices are essential to getting into safe mode. The radio is needed only after the spacecraft has completed other steps.

The spacecraft will not complete those other steps. One of them is to turn to point at the Sun, ensuring that the large solar arrays are fully illuminated. But without hydrazine, it will have no means to accomplish the necessary turn.

So, Dawn will not be able to achieve the planned orientation with the solar arrays generating electrical power. The computer will stubbornly refuse to turn on the radio, instead continuing to try to turn so the Sun will light up the arrays and infuse the robot with its electrical lifeblood.

Dawn will continue to try as long as it has power, whether flowing from partially lit solar arrays or from the battery. All the while, the spacecraft will continue to rotate at the same leisurely speed it did when it had hydrazine. But instead of gently oscillating back and forth, it will simply keep going in the same direction, like a clock's hour hand slowed down to measure months instead of hours.

Some of the time, the solar arrays will face away from the Sun and the battery will drain. Some of the time the solar arrays will point at (or near) the Sun just by luck. But Dawn doesn't rely on luck. Until it has a stable orientation with the arrays reliably on the Sun, the computer will insist that power not be devoted to the radio. First things first: first achieve a condition that can be safe for days, weeks, or even months, and then radio Earth for help. The programming did not anticipate being completely unable to control orientation.

Engineers have analyzed what will happen and observed many examples of it in the spacecraft simulator at JPL. Eventually, the computer may make some other attempts. But Dawn's struggle will be brief, lasting only hours before the battery is exhausted. The seasoned adventurer will sink into unconsciousness. At some later time, as its stately rotation brings the solar arrays back into the light, it may well begin to revive, but the cycle will repeat. The newly awakened Dawn will try to point at the Sun and hold that position, taking advantage of the power from the fortuitously illuminated solar arrays. But soon its continuing rotation will point the arrays into the dark of space again. It might seem that half the time the arrays would receive light and so it should be able to operate at half power, but it doesn't work that way. At Dawn's distance from the Sun, a little bit of that faint light on the solar arrays is not sufficient.

After an extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition, more than a decade of interplanetary travels, unveiling two of the last uncharted worlds in the inner solar system, performing unique and complex maneuvers, encountering and overcoming a host of unanticipated problems, Dawn will be on the losing end of a battle with the cold, hard reality of operation in deep space. Its mission will be over.

The spacecraft will be well over a million times farther from Earth than the International Space Station. How will we know when it has run out of hydrazine if its radio is off? (The reaction control system is expected to operate normally as long as there is usable hydrazine, so there will be no prior indication that its exhaustion is imminent.)

Even as it goes about trying to fix or recover from problems, the computer issues some brief status reports. (They often are more informative than the dialog boxes that pop up on your computer, and Dawn never asks you to click on something to proceed.) If the loss of hydrazine happens to occur while Dawn is communicating with Earth, one of those concise reports may be received before the computer turns off the transmitter. The short message would be like a farewell tweet that Dawn is ending its mission.

Most of the time, however, the probe does not point its main antenna at Earth. When it zips down to low altitude, it aims its sensors at the ground, so the antenna is pointed in an arbitrary direction. Dawn transmits a very broad radio signal through one of its auxiliary antennas so scientists and engineers can follow its motion very precisely. (We have explained before that this allows them to determine the interior structure of the dwarf planet.) That radio connection is too weak for anything else, so Dawn won't be able to tweet its news. If the last of the hydrazine is spent when Dawn's orbital motion is being tracked, the radio signal will simply disappear.

In its elliptical orbit, Dawn spends far less time traveling fast at low altitude than it does traveling slowly at high altitude, much as the girl on a swing we encountered in April. And when it is high up, we generally do not have radio contact at all. So it is more likely that the hydrazine will be depleted when Dawn is out of touch than when the DSN is recording its radio transmissions, through either the main antenna or an auxiliary antenna. Then the next time one of the antennas of the DSN aims at Dawn's location in the sky, it will strain to hear the faint radio whisper of the faraway probe, but all will be silent.

Dawn controllers and the DSN will work together to be sure the inability to detect the spacecraft isn't some other problem, perhaps in mission control or in the tremendously complex DSN. Over the course of a few days, they will use more than one antenna and will take a few other measures. After all, there could be other reasons for a temporary loss of signal, and engineers will work through the possibilities. But given Dawn's resilience and sophistication, if it remains uncommunicative during that time, the conclusion will not be in doubt. Even without a tweet, it will be clear Dawn has run out of hydrazine and is at the end of its operational life.

After conducting a systematic investigation, when the Dawn project is confident of the situation, we will announce the result. In the next Dawn Journal, we will consider a more personal side of this story.

But what of Dawn's long-term fate? Remember, its orientation in space is largely independent of its orbital motion. The spacecraft's inability to point where it wants, to power its systems, and to communicate with its human handlers will have virtually no effect on where it goes.

Dawn doesn't need propulsion to stay in orbit around Ceres, just as the Moon doesn't need it to stay in orbit around Earth and Earth doesn't need it to stay in orbit around the Sun. And that's important. We do not want Dawn to come into contact any time soon with the dwarf planet it orbits.

Ceres is subject to planetary protection, a set of standards designed to ensure the integrity of possible future "biological exploration" of the alien world. That terminology does not mean there is biology on Ceres but rather that that exotic world is of interest in the field of astrobiology. Ceres was once covered with an ocean and today harbors a vast inventory of water (mostly as ice but perhaps with some liquid still present underground). It also has a supply of heat (retained even now, long after radioactive elements decayed and warmed the interior), organics and a rich variety of other chemicals. With all these ingredients, Ceres could experience some of the chemistry related to the development of life. Scientists do not want to contaminate that pristine environment with Dawn's terrestrial materials.

Not all solar system bodies need such protection. The Moon, Mercury and Venus, for example, have not been of interest for searches for life or for prebiotic chemistry. For that reason, spacecraft are allowed to land or crash on those worlds because there is no expectation of subsequent biological exploration. Also exempt from such rules are tiny asteroids, including two that are being explored this year, Ryugu and Bennu. They are entirely unlike giant Ceres. They are often mistakenly thought of as being similar because of the oversimplified notion that all are asteroids. We will provide an illustration of the dramatic difference in the next Dawn Journal.

The planetary protection rules for Ceres specify that Dawn not be allowed to contact it for at least 20 years. There is a common misconception that the time is needed to allow the spacecraft to be sterilized by the radiation, vacuum and temperature extremes of spaceflight. That's not the case. Many terrestrial microbes are impressively hardy, and there is good reason to believe that some that have taken an unplanned interplanetary cruise with Dawn would remain viable after much longer than 20 years.

The requirement for 20 years is intended to allow enough time for a follow-up mission, if deemed of sufficiently high priority given the many goals NASA has for exploring the solar system. Two decades should be long enough to mount a mission that builds on Dawn's many discoveries. We would not want such a hypothetical mission to be misled by finding microorganisms or nonbiological organic chemicals that were deposited by our spacecraft. As we'll see below, the deadline for another mission to get there before Dawn contaminates Ceres is likely to be significantly more relaxed even than that.

Earlier this year, when the team was figuring out how to fly to and operate in an orbit like the one Dawn is in now, much of their work was guided by this planetary protection requirement. We did not want to enter an orbit that would not meet the 20-year lifetime. We could not take the chance of going to an orbit with a shorter lifetime and plan for subsequent maneuvers to increase the duration. We were not sufficiently confident Dawn would have enough hydrazine to remain operable long enough to make its observations and still be able to change its orbit.

The team studied elliptical orbits with different minimum altitudes. Trajectory experts investigated the long-term behavior of each orbit as Ceres' irregular gravity field tugs on the spacecraft revolution after revolution, year after year. Like Earth, Ceres has some regions of higher density and some of lower density. As Dawn orbits over these different regions, they gradually distort the orbit. The analyses also accounted for the slight pressure of sunlight, which not only can rotate the spacecraft but also can push it in its orbit. An orbit with a minimum of 22 miles (35 kilometers) was the lowest that the team was confident would comply with planetary protection, and that's why Dawn is now in just such an orbit.

And after 20 years? Calculations show that even over 50 years, the orbital perturbations are overwhelmingly likely to be too small to cause Dawn to crash. In fact, there is less than a one percent chance of the orbit being distorted enough that Dawn would hit Ceres. In other words, our analysis gives us more than 99 percent confidence that even in half a century, Dawn will still be revolving around Ceres, the largest object between Mars and Jupiter, the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system and the first dwarf planet discovered (129 years before Pluto).

Leaving the remarkable craft in orbit around the distant colossus will be a fitting and honorable conclusion to its historic journey of discovery at Vesta and Ceres. Dawn's scientific legacy is secure, having revealed myriad fascinating and exciting insights into two quite dissimilar and mysterious alien worlds. This interplanetary ambassador from Earth will be an inert celestial monument to the power of human ingenuity, creativity, and curiosity, a lasting reminder that our passion for bold adventures and our noble aspirations to know the cosmos can take us very, very far beyond the confines of our humble home.

Dawn is 1,400 miles (2,300 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 3.46 AU (321 million miles, or 517 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,270 times as far as the Moon and 3.42 times as far as the Sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 58 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

7:00 pm PDT August 21, 2018

TAGS: DAWN, CERES, DWARF PLANET, ASTEROID BELT, SPACECRAFT, ASTROBIOLOGY

Dawn Journal | April 29, 2016

New Dimensions and More Discoveries Lie Ahead for Dawn

Dear Glutdawnous Readers,

The distant dwarf planet that Dawn is circling is full of mystery and yet growing ever more familiar.

Ceres, which only last year was hardly more than a fuzzy blob against the stars, is now a richly detailed world, and our portrait grows more elaborate every day. Having greatly surpassed all of its original objectives, the reliable explorer is gathering still more data from its unique vantage point. Everyone who hungers for new knowledge about the cosmos or for bold adventures far from Earth can share in the sumptuous feast Dawn has been serving.

One of the major objectives of the mission was to photograph 80 percent of Ceres' vast landscape with a resolution of 660 feet (200 meters) per pixel. That would provide 150 times the clarity of the powerful Hubble Space Telescope. Dawn has now photographed 99.8 percent with a resolution of 120 feet (35 meters) per pixel.

This example of Dawn's extraordinary productivity may appear to be the limit of what it could achieve. After all, the spaceship is orbiting at an altitude of only 240 miles (385 kilometers), closer to the ground than the International Space Station is to Earth, and it will never go lower for more pictures. But it is already doing more.

Since April 11, instead of photographing the scenery directly beneath it, Dawn has been aiming its camera to the left and forward as it orbits and Ceres rotates. By May 25, it will have mapped most of the globe from that angle. Then it will start all over once more, looking instead to the right and forward from May 27 through July 10. The different perspectives on the terrain make stereo views, which scientists can combine to bring out the full three dimensionality of the alien world. Dawn already accomplished this in its third mapping orbit from four times its current altitude, but now that it is seeing the sights from so much lower, the new topographical map will be even more accurate.

Dawn is also earning extra credit on its assignment to measure the energy of gamma rays and neutrons. We have discussed before how the gamma ray and neutron detector (GRaND) can reveal the atomic composition down to about a yard (meter) underground, and last month we saw initial findings about the distribution of hydrogen. However, Ceres' nuclear glow is very faint. Scientists already have three times as much GRaND data from this low altitude as they had required, and both spectrometers in the instrument will continue to collect data. In effect, Dawn is achieving a longer exposure, making its nuclear picture of Ceres brighter and sharper.

In December we explained how using the radio signal to track the probe's movements allows scientists to chart the gravity field and thereby learn about the interior of Ceres, revealing regions of higher and lower density. Once again, Dawn performed even better than expected and achieved the mission's planned accuracy in the third mapping orbit. Because the strength of the dwarf planet's gravitational tug depends on the distance, even finer measurements of how it varies from location to location are possible in this final orbit. Thanks to the continued smooth operation of the mission, scientists now have a gravitational map fully twice as accurate as they had anticipated. With additional measurements, they may be able to squeeze out a little more detail, perhaps improving it by another 20 percent before reaching the method's limit.

Dawn has dramatically overachieved in acquiring spectra at both visible and infrared wavelengths. We have previously delved into how these measurements reveal the minerals on the ground and what some of the interesting discoveries are. Having already acquired more than seven times as many visible spectra and 21 times as many infrared spectra as originally called for, the spacecraft is adding to its riches with additional measurements. We saw in January that VIR has such a narrow view that it will never see all of Ceres from this close, so it is programmed to observe features that have caught scientists' interest based on the broad coverage from higher altitudes.

Dawn's remarkable success at Ceres was not a foregone conclusion. Of course, the flight team has confronted the familiar challenges people encounter every day in the normal routine of piloting an ion-propelled spaceship on a multibillion-mile (multibillion-kilometer) interplanetary journey to orbit and explore two uncharted worlds. But the mission was further complicated by the loss of two of the spacecraft's four reaction wheels, as we have recounted before. (In full disclosure, the devices aren’t actually lost. We know precisely where they are. But given that one stopped functioning in 2010 and the other in 2012, they might as well be elsewhere in the universe; they don’t do Dawn any good.) Without three of these units to control its orientation in space, the robot has relied on its limited supply of hydrazine, which was not intended to serve this function. But the mission's careful stewardship of the precious propellant has continued to exceed even the optimistic predictions, allowing Dawn good prospects for carrying on its fruitful work. In an upcoming Dawn Journal, we will discuss how the last of the dwindling supply of hydrazine may be used for further discoveries.

In the meantime, Dawn is continuing its intensive campaign to reveal the dwarf planet's secrets, and as it does so, it is passing several milestones. The adventurer has now been held in Ceres' tender but firm gravitational embrace longer than it was in orbit around Vesta. (Dawn is the only spacecraft ever to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations, and its mission would have been impossible without ion propulsion.) The spacecraft provided us with about 31,000 pictures of Vesta, and it has now acquired the same number of Ceres.

For an interplanetary traveler, terrestrial days have little meaning. They are merely a memory of how long a faraway planet takes to turn on its axis. Dawn left that planet long ago, and as one of Earth's ambassadors to the cosmos, it is an inhabitant of deep space. But for those who keep track of its progress yet are still tied to Earth, on May 3 the journey will be pi thousand days long. (And for our nerdier friends and selves, it will be shortly after 6:47 p.m. PDT.)

By any measure, Dawn has already accomplished an extraordinary mission, and there is more to look forward to as its ambitious expedition continues.

Dawn is 240 miles (385 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 3.73 AU (346 million miles, or 558 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,455 times as far as the moon and 3.70 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take one hour and two minutes to make the round trip.

TAGS: CERES, DAWN, MISSION, SPACECRAFT, VESTA, DWARF PLANET

Dawn Journal | March 31, 2016

Dawn 'Fueled' for Even More Discoveries at Ceres

Dear Resplendawnt Readers,

One year after taking up its new residence in the solar system, Dawn is continuing to witness extraordinary sights on dwarf planet Ceres. The indefatigable explorer is carrying out its intensive campaign of exploration from a tight orbit, circling its gravitational master at an altitude of only 240 miles (385 kilometers).

Even as we marvel at intriguing pictures and other discoveries, scientists are still in the early stages of putting together the pieces of the big puzzle of how (and where) Ceres formed, what its subsequent history has been, what geological processes are still occurring on this alien world and what all that reveals about the solar system.

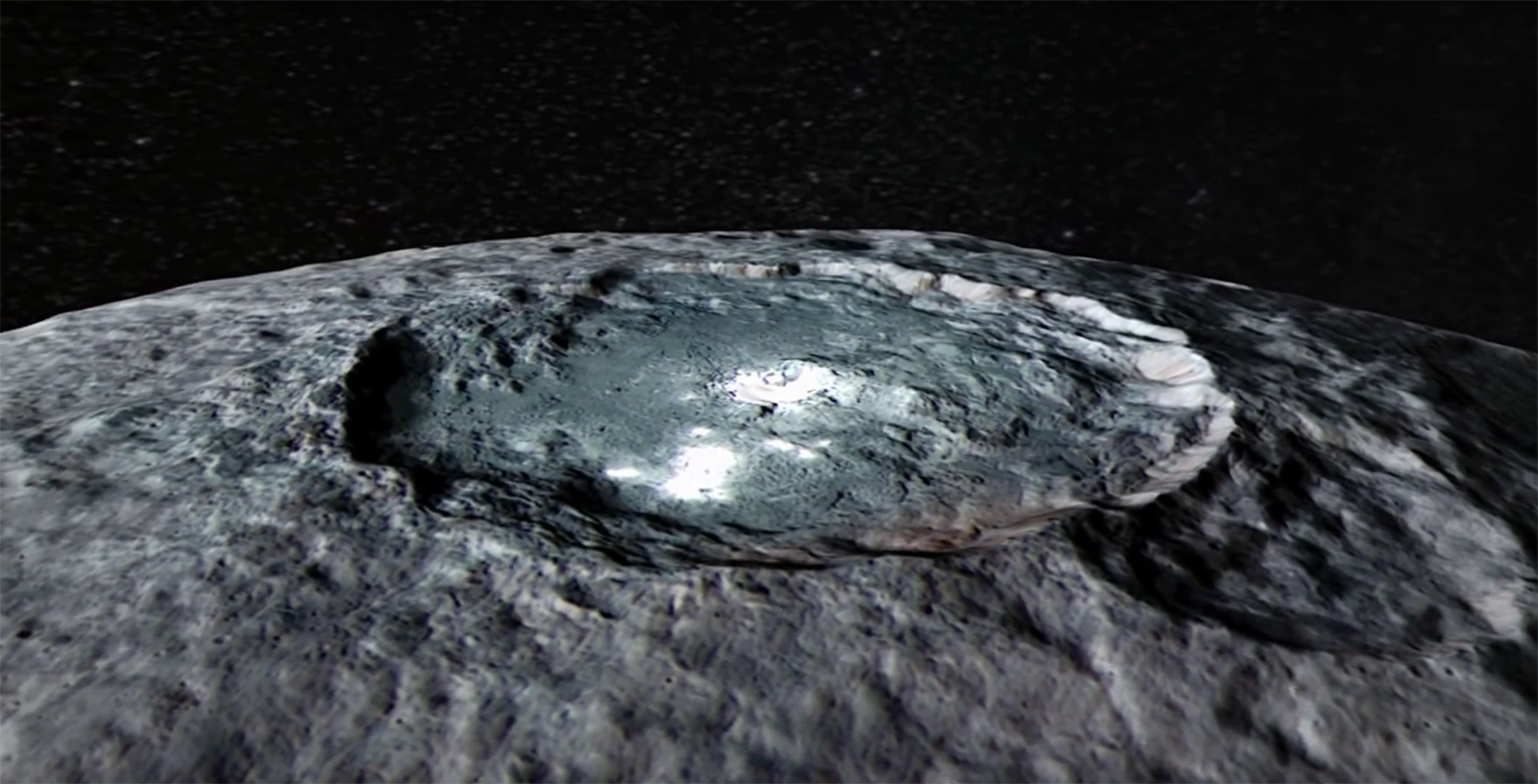

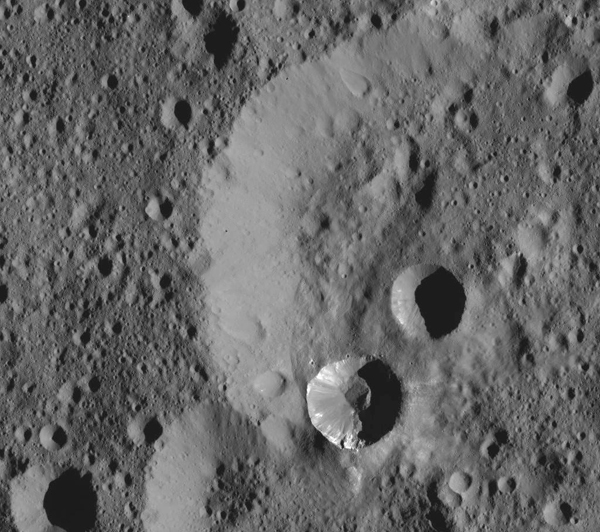

For many readers who have not visited Ceres on their own, Occator Crater is the most mysterious and captivating feature. (To resolve the mystery of how to pronounce it, listen to the animation below.) As Dawn peered ahead at its destination in the beginning of 2015, the interplanetary traveler observed what appeared to be a bright spot, a shining beacon guiding the way for a ship sailing on the celestial seas. With its mesmerizing glow, the uncharted world beckoned, and Dawn answered the cosmic invitation by venturing in for a closer look, entering into Ceres' gravitational embrace. The latest pictures are one thousand times sharper than those early views. What was not so long ago a single bright spot has now come into focus as a complex distribution of reflective material in a 57-mile (92-kilometer) crater.

Scientists are still working on refining their understanding of this striking region. As we described in December, it seems that following the powerful impact that excavated Occator Crater, underground briny water reached the surface. The detailed photographs show many fractures cutting across the bright areas, and perhaps they provided a conduit. Water, whether as liquid or ice, would not last long there in the cold vacuum, eventually subliming. When the water molecules disperse, either escaping from Ceres into space or falling back to settle elsewhere, the dissolved salts are left behind. This reflective residue covers the ground, making the spellbinding and beautiful display Dawn now reveals.

While the crater is estimated to be a geological youngster at 80 million years old, that is an extremely long time for the material to remain so reflective. Exposed for so long to cosmic radiation and pelting from the rain of debris from space, it should have darkened. Scientists don't know (yet) what physical process are responsible, but perhaps it was replenished long after the crater itself formed, with more water, carrying dissolved salts, finding its way to the surface. As their analyses of the photos and spectra continue, scientists will gain a clearer picture and be able to answer this and other questions.

These latest Occator pictures did not come easily. Orbiting so close to Ceres, the adventurer’s camera captures only a small scene at a time, and it is challenging to cover the entirety of the expansive terrain. (Perhaps it comes as a surprise to those who have not read at least a few of the 123 Dawn Journals that precede this one that operating a spacecraft closer to a faraway dwarf planet than the International Space Station is to Earth is not as easy as, say, thinking about it.) But the patience and persistence in photographing the exotic landscapes have paid off handsomely.

We now have high resolution pictures of essentially all of Ceres save the small area around the south pole cloaked in the deep dark of a long winter night. Seasons last longer on Ceres than on Earth, and Dawn may not operate there long enough for the sun to rise at the south pole. By the beginning of southern hemisphere spring in November 2016, Dawn's mission to explore the first dwarf planet discovered may have come to its end.

In addition to photographing Ceres, Dawn conducts many other scientific observations, as we described in December and January. Among the probe's objectives at Ceres is to provide information for scientists to understand how much water is there, where it is, what form it is in and what role it plays in the geology.

We saw that extensive measurements of the faint nuclear radiation can help identify the atomic constituents. While the analysis of the data is complicated, and much more needs to be done, a picture is beginning to emerge from Dawn's neutron spectrometer (part of the gamma ray and neutron detector, GRaND). These subatomic particles are emitted from the nuclei of atoms buried within about a yard (meter) of the surface. Some manage to penetrate the material above them and fly into space, and the helpful ones then meet their fate upon hitting GRaND in orbit above. (Most others, however, will continue to fly through interplanetary space, decaying into a trio of other subatomic particles in less than an hour.) Before it escapes from the ground, a neutron's energy (and, equivalently, its speed) is strongly affected by any encounters with the nuclei of hydrogen atoms (although other atomic interactions can change the energy too). Therefore, the neutron energies can indicate to scientists the abundance of hydrogen. Among the most common forms in which hydrogen is found is water (composed of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom), which can occur as ice or tied up in hydrated minerals.

GRaND shows Ceres is rich in hydrogen. Moreover, it detects more neutrons in an important energy range near the equator than near the poles, likely indicating there is more hydrogen, and hence more (frozen) water, in the ground at the high latitudes. Although Ceres is farther from the sun than Earth, and you would not consider it balmy there, it still receives some warmth. Just as at Earth, the sun's heating is less effective closer to the poles than at low latitudes, so this distribution of ice in the ground may reflect the temperature differences. Where it is warmer, ice close to the surface would have sublimed more quickly, thus depleting the inventory compared to the cooler ground far to the north or south.

Dawn spends most of its time measuring neutrons (and gamma rays), so it is providing a great deal of new data. And as scientists conduct additional analyses, they will learn more about the ice and other materials beneath the surface.

Another spectrometer is providing more tantalizing clues about the composition of Ceres, which is seen to vary widely. As the dwarf planet is not simply a huge rock but is a geologically active world, it is no surprise that it is not homogeneous. We discussed in December that the infrared mapping spectrometer had shown that minerals known as phyllosilicates are common on Ceres. Further studies of the data show evidence for the presence of two types: ammoniated phyllosilicates (described in December) and magnesium phyllosilicates. Scientists also find evidence of compounds known as carbonates, minerals that contain carbon and oxygen. There is also a dark substance in the mix that has not been identified yet.

And in one place (so far) on Ceres, this spectrometer has directly observed water, not below the surface but on the ground. The infrared signature shows up in a small crater named Oxo. (For the pronunciation, listen to the animation below.) As with the neutron spectra, it is too soon to know whether the water is in the form of ice or is chemically bound up in minerals.

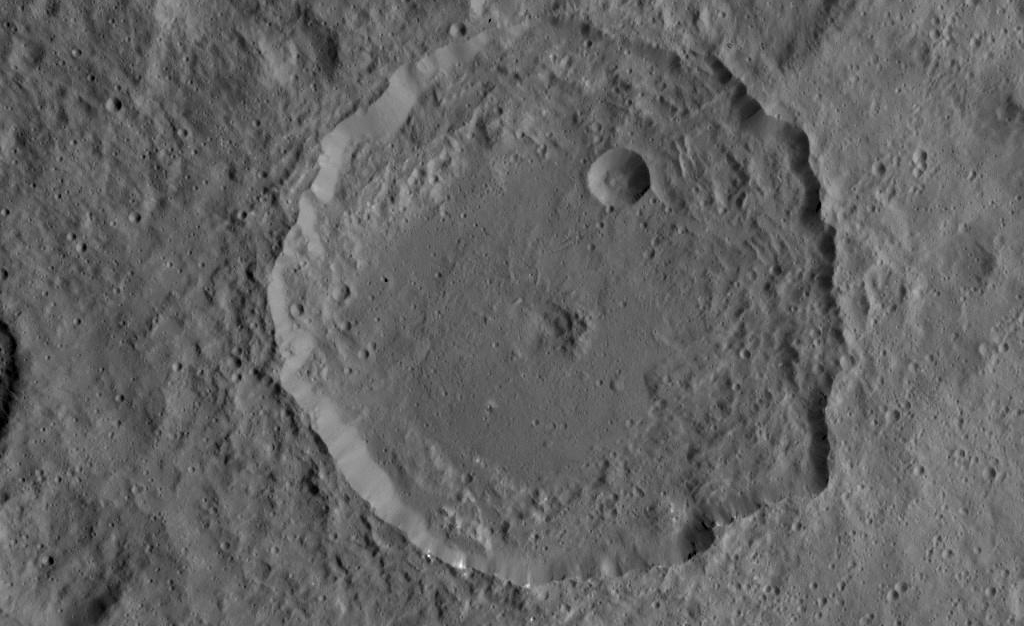

At six miles (10 kilometers) in diameter, Oxo is small in comparison to the largest craters on Ceres, which are more than 25 times wider. (While geologists consider it a small crater, you might not agree if it formed in your backyard. Also note that when we showed Oxo Crater before, the diameter was slightly different. The crater's size has not changed since then, but as we receive sharper pictures, our measurements of feature sizes do change.) Dawn's first orbital destination, the fascinating protoplanet Vesta, is smaller than Ceres and yet has two craters far broader than the largest on Ceres. Based on studies of craters observed throughout the solar system, scientists have established methods of calculating the number and sizes of craters that could be formed on planetary surfaces. Those techniques show that Ceres is deficient in large craters. That is, more should have formed than appear in Dawn's pictures. Many other bodies (including Vesta and the moon) seem to preserve their craters for much longer, so this may be a clue about internal geological processes on Ceres that gradually erase the large craters.

Scientists are still in the initial stages of digesting and absorbing the tremendous wealth of data Dawn has been sending to Earth. The benefit of lingering in orbit (enabled by the remarkable ion propulsion system), rather than being limited to a brief glimpse during a fast flyby, is that the explorer can undertake much more thorough studies, and Dawn is continuing to make new measurements.

As recently as one year ago, controllers (and this writer) had great concern about the spacecraft's longevity given the loss of two reaction wheels, which are used for controlling the ship's orientation. And in 2014, when the flight team worked out the intricate instructions Dawn would follow in this fourth and final mapping orbit, they planned for three months of operation. That was deemed to be more than enough, because Dawn only needed half that time to accomplish the necessary measurements. Experienced spacecraft controllers recognize that there are myriad ways beautiful plans could go awry, so they planned for more time in order to ensure that the objectives would be met even if anomalies occurred. They also were keenly aware that the mission could very well conclude after three months of low altitude operations, with Dawn using up the last of its hydrazine. But their efforts since then to conserve hydrazine proved very effective. In addition, the two remaining wheels have been operating well since they were powered on in December, further reducing the consumption of the precious propellant.

As it turned out, operations have been virtually flawless in this orbit, and the first three months yielded a tremendous bounty, even including some new measurements that had not been part of the original plans. And because the entire mission at Ceres has gone so well, Dawn has not expended as much hydrazine as anticipated.

Dawn is now performing measurements that were not envisioned long in advance but rather developed only in the past two months, when it was apparent that the expedition could continue. And since March 19, Dawn has been following a new strategy to use even less hydrazine. Instead of pointing its sensors straight down at the scenery passing beneath it as the spacecraft orbits and Ceres rotates, the probe looks a little to the left. The angle is only five degrees (equal to the angle the minute hand of a clock moves in only 50 seconds, or less than the interval between adjacent minute tick marks), but that is enough to decrease the use of hydrazine and thus extend the spacecraft's lifetime. (We won't delve into the reason here. But for fellow nerds, it has to do with the alignment of the axes of the operable reaction wheels with the plane in which Dawn rotates to keep its instruments pointed at Ceres and its solar arrays pointed at the sun. The hydrazine saving depends on the wheels' ability to store angular momentum and applies only in hybrid control, not in pure hydrazine control. Have fun figuring out the details. We did!)

The angle is small enough now that the pictures will not look substantially different, but they will provide data that will help determine the topography. (Measurements of gravity and the neutron, gamma ray and infrared spectra are insensitive to this angle.) Dawn took pictures at a variety of angles during the third mapping orbit at Ceres (and in two of the mapping orbits at Vesta, HAMO1 and HAMO2) in order to get stereo views for topography. That worked exceedingly well, and photos from this lower altitude will allow an even finer determination of the three dimensional character of the landscape in selected regions. Beginning on April 11, Dawn will look at a new angle to gain still another perspective. That will actually increase the rate of hydrazine expenditure, but the savings now help make that more affordable. Besides, this is a mission of exploration and discovery, not a mission of hydrazine conservation. We save hydrazine when we can in order to spend it when we need it. Dawn's charge is to use the hydrazine to accomplish important scientific objectives and to pursue bold, exciting goals that lift our spirits and fuel our passion for knowledge and adventure. And that is exactly what it is has done and what it will continue to do.

Dawn is 240 miles (385 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 3.90 AU (362 million miles, or 583 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,505 times as far as the moon and 3.90 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take one hour and five minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

4:00 p.m. PDT March 31, 2016

TAGS: CERES, DAWN, MISSION, SPACECRAFT, VESTA, DWARF PLANET

Dawn Journal | February 29, 2016

Mission Accomplished But the Journey Continues ...

Dear Indawnbitably Successful Readers,

A story of intense curiosity about the cosmos, passionate perseverance and bold ingenuity, a story more than two centuries in the making, has reached an extraordinary point. It begins with the discovery of dwarf planet Ceres in 1801 (129 years before its sibling Pluto; each was designated a planet for a time). Protoplanet Vesta was discovered in 1807. Following 200 years of telescopic observations, Dawn's daring mission was to explore these two uncharted worlds, the largest, most massive residents of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. And now, as of February 2016, the spacecraft has accomplished all of the objectives that NASA defined for it in 2004, even before construction began (and before the very first Dawn Journal, nearly a decade ago).

More than eight years after leaving its erstwhile planetary home behind for an ambitious deep space adventure, Dawn has now collected all of the data originally planned. Indeed, even prior to this third intercalary day of its expedition, the probe had already actually sent back a great deal more data for all investigations, significantly exceeding not only the original goals but also new ones added after the ship had set sail on the interplanetary seas. While scientists have a great deal of work still ahead to translate the bounty of data into knowledge, which is the greatest joy of science, the spacecraft can continue its work with the satisfaction that it has fulfilled its purpose and achieved an outstandingly successful mission.

Dawn is the only spacecraft ever to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations, which would have been impossible without its advanced ion propulsion system. It is the only spacecraft ever to orbit an object in the main asteroid belt. It is also the only spacecraft ever to orbit massive bodies (apart from the sun and Earth) that had not been visited first by a flyby spacecraft to characterize the gravity and other properties. (By the way, Ceres is one of eight solar system bodies that operating spacecraft are orbiting now. The others are the sun, Venus, Earth, the moon, comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko, Mars and Saturn.)

Now in its fourth and final mapping orbit at Ceres, at an altitude of 240 miles (385 kilometers), Dawn is closer to the exotic terrain than the International Space Station is to Earth. The benefit of being in orbit is that the probe can linger rather than take only a brief look during a fast flyby. Even though Dawn has met its full list of objectives at Ceres, it continues to return new, valuable pictures and other measurements to provide even greater insight into this relict from the dawn of the solar system. For example, it is acquiring more nuclear spectra with its gamma ray and neutron detector, sharpening its picture of some atomic elements on Ceres. In addition, taking advantage of its unique vantage point, Dawn is collecting more infrared spectra of locations that are of special interest and soon will also take color photos and stereo photos (as it did in the third mapping orbit) of selected areas.

Dawn has completed more than 600 revolutions since taking up residence one year ago. The first few orbits took several weeks each, but as the spacecraft descended and Ceres' gravitational embrace grew more firm, its orbital velocity increased and the orbital period decreased. Now circling in less than five and a half hours, Dawn has made 370 orbits since reaching this altitude on Dec. 7.

The pace of observations here is higher than in the previous mapping orbits, where the orbital periods were longer. The spacecraft flies over the landscape faster now, and being closer to the ground, its instruments discern much more detail but capture a smaller area. Mission controllers have developed intricate plans for observing Ceres, but those plans depend on the spacecraft being at the right place at the right time. As we will see below, however, sometimes it may not be.

Suppose, for example, the intent is to observe a particular feature, perhaps the bright center of Occator crater, the lonely, towering mountain Ahuna Mons, the fractures in Dantu crater or artificial structures that definitively prove the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence, utterly transforming our understanding of the cosmos and shattering our naive perspectives on life in the universe. Trajectory analysis indicates when Dawn will fly over the designated location, and engineers will program it to take pictures or infrared spectra at that time. They will also include some margin, so they may program it to start 10 minutes before and end 10 minutes after. But they can't afford to put in too much margin. Data storage on the spacecraft is limited, so other geological features could not be observed. Also, transmitting data to Earth requires pointing the main antenna at that distant planet instead of pointing sensors at Ceres, so it would be unwise to collect much more than is necessary.

Even if devoting additional time (and data) to trying to observe the desired place were feasible, it wouldn't necessarily solve the problem. Dawn travels in a polar orbit, which is the only way to ensure that it passes over all latitudes. While Dawn soars from north to south over the sunlit hemisphere making its observations, the dwarf planet itself rotates on its axis, so the ground moves from east to west. If the spacecraft arrives at the planned orbital location a little early or a little late, the feature of interest may not even be beneath it but rather could be too far east or west, out of view of the instruments. In that case, increasing the duration of the observation period doesn't help.

All of that is why, as we saw last month, it requires more pictures to fully map Ceres than you might expect. Many pictures may have to be taken in order to fill in gaps, and quite a few of the pictures overlap with others. Nevertheless, Dawn has done an excellent job. The spacecraft has photographed 99.6 percent of the dwarf planet from this low altitude. (If you aren't regularly visiting the image gallery, you are missing out on some truly out-of-this-world scenes.)

The flight team devises very detailed plans that tell the spacecraft what to do every second, including where to point and what data to collect with each sensor. When the observation plans are developed, they are checked and double-checked. Then they are translated into the appropriate software that the robotic ship will understand, and these instructions are checked and double-checked. That is integrated with all the other software that will be beamed to the spacecraft covering the same period of time, any conflicts are resolved and then the final version is checked and, well, you know.

This process is very involved, and it is usually well over a month between the formulation and the execution of the plan. During that time, Dawn's orbit can deviate slightly from the expert navigators' mathematical predictions, preventing the spacecraft from flying over the desired targets. There are several reasons the actual orbit may differ from the orbit used for developing the plan. (We have seen related examples of this, including as Dawn approached Mars, when it orbited Vesta and when it spiraled from one mapping orbit to another.) Let's briefly consider two.

One reason is that we do not have perfect knowledge of the variations in the strength of Ceres' gravitational pull from one location to another. We have discussed before that measuring these tiny irregularities in the gravity field provides insight into the distribution of mass within the dwarf planet that gives rise to them. The team has mapped the hills and valleys of the field quite well and even better than expected. Still, the remaining small uncertainty can lead to slight differences between what navigators calculate Dawn's motion will be and what its actual motion will be as it is buffeted by the gravitational currents.

A second source of discrepancy is that Dawn's own activities distort its orbit. Every time the reaction control system expels a tiny burst of hydrazine to control the spacecraft's orientation, keeping it pointed at its target, the force not only affects the orientation but also nudges the probe in its orbit, slowing it down or speeding it up very slightly. It's up to the spacecraft to decide exactly when to make these small adjustments, and it is not possible for controllers to predict their timing. (In a similar way, when you are driving, you occasionally move the steering wheel to keep going the direction you want, even if is straight ahead. It would be impossible to forecast each tiny movement, because they all depend on what has already happened plus the exact conditions at the moment.) The details of the reaction control system activity also depend on the use of the novel hybrid control scheme, which the joint Orbital/JPL team developed because of the failure of two of the spacecraft's four reaction wheels. The effect of each small firing of hydrazine is very small, but they can add up.

It took about a month in this mapping orbit to discover many of the subtleties of the gravity field and gain experience with how hybrid control affects the orbit. But even before descending to this altitude, the operations team understood the nature of these effects and was well prepared to deal with them.

They devised several strategies, all of which are being used to good effect. One of the ways to account for Dawn's actual orbit differing from its planned orbit is simply to change the orbit. Simply? Well, not really. It turns out to that to analyze the orbit and then maneuver to correct it in a timely way is a surprisingly complicated process, but, come to think of it, what isn't complicated when flying a spaceship around a distant, alien world? Nevertheless, every three weeks, the flight team makes a careful assessment of the orbit and determines whether a small refinement with the ion propulsion system is in order. For technical reasons, if maneuvers are needed, they will be executed in pairs, so mission planners have scheduled two windows (each 12 hours long and separated by eight days) about every 23 days.

Adjustments to resynchronize the actual orbit with the predicted orbit that formed the basis of the exploration plan are known as “orbit maintenance maneuvers.” Succumbing to instincts developed during their long evolutionary history, engineers refer to them by an acronym: OMM. (As the common thread among team members is their technical training and passion for the exploration of the cosmos, and not Buddhism, the term is spoken by naming the letters, not pronouncing it as if it were a means of achieving inner peace. Instead, it may be thought of as a means of achieving orbital tranquility and harmony.)

For both Vesta and Ceres, trajectory analyses long in advance determined that OMMs would not be needed in the higher orbits, so no windows were included in those schedules. There have been three OMM opportunities since arriving at the lowest altitude above Ceres, but only the first was needed. Dawn performed the pair on Dec. 31-Jan. 1 and on Jan. 8 with its famously efficient ion engine. The orbit was good enough the next two times that OMMs were deemed unnecessary. It is certain that some future OMMs will be required. Your faithful correspondent provides frequent (and uncharacteristically concise) reports on Dawn's day-to-day activities, including OMMs.

By the end of the Jan. 8 OMM, Dawn's ion propulsion system had accumulated 2,019 days of operation in space, more than 5.5 years. During that time, the effective change in speed was 24,600 mph (39,600 kilometers per hour). (We have discussed in detail that this is not Dawn's current speed but rather the amount by which the ion engines have changed it.) This is uniquely high for a spacecraft to accomplish with its own propulsion system and validates our description of ion propulsion as delivering acceleration with patience. (The previous record holder, Deep Space 1, achieved 9,600 mph, or 15,000 kilometers per hour.)

The effect of Dawn's gentle ion thrusting during its mission has been nearly the same as that of the entire Delta II 7925H-9.5 rocket, with its nine external rocket engines, first stage, second stage and third stage. To get started on its interplanetary adventure, Dawn's rocket boosted it from Cape Canaveral to out of Earth orbit with only four percent higher velocity than Dawn subsequently added on its own with its ion engines.

As Dawn and Earth follow their own independent orbits around the sun (Dawn's now tied permanently to its gravitational master, Ceres), next month they will reach their greatest separation of the entire mission. On March 4 (about one Earth year after Ceres took hold of Dawn), on opposite sides of the solar system, they will be 3.95278 AU (367.434 million miles, or 591.328 million kilometers) from each other. (For those of you with full schedules, note that the maximum separation will be 5:40 a.m. PST.) They won't be this far apart again until Feb. 6, 2025, long after Dawn has ceased operating (as discussed below). The figure below depicts the arrangement next month.

Dawn has faced many challenges in its unique voyage in the forbidding depths of space, but it has surmounted all of them. It has even overcome the dire threat posed by the loss of two reaction wheels (the second failure occurring in orbit around Vesta 3.5 years and 1.3 billion miles, or 2.0 billion kilometers, ago). With only two operable reaction wheels (and those no longer trustworthy), the ship's remaining lifetime is very limited.

A year ago, the team couldn't count on Dawn even having enough hydrazine to last beyond next month. But the creative methods of conserving that precious resource have proved to be quite efficacious, and the reliable explorer still has enough hydrazine to continue to return bonus data for a while longer. Now it seems highly likely that the spacecraft will keep functioning through the scheduled end of its primary mission on June 30, 2016.

NASA may choose to continue the mission even after that. Such decisions are difficult, as there is literally an entire universe full of interesting subjects to study, but resources are more limited. In any case, even if NASA extended the mission, and even if the two wheels operated without faltering, and even if the intensive campaign of investigating Ceres executed flawlessly, losing not an ounce (or even a gram) of hydrazine to the kinds of glitches that can occur in such a complex undertaking, the hydrazine would be exhausted early in 2017. Clearly an earlier termination remains quite possible.

Regardless of when Dawn's end comes, it will not be a time for regret. The mission has realized its raison d'être and is reaping rewards even beyond those envisioned when it was conceived. It has taken us all on a marvelous interplanetary journey and allowed us to behold previously unseen sights of distant lands. The conclusion of the mission will be a time for gratitude that it was so successful. And until then, every new picture or other measurement adds to the richly detailed portrait of a faraway, exotic world. There is plenty more still to do before this remarkable story draws to a close.

Dawn is 240 miles (385 kilometers) from Ceres. It is also 3.95 AU (367 million miles, or 591 million kilometers) from Earth, or 1,475 times as far as the moon and 3.99 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take one hour and six minutes to make the round trip.

TAGS: DAWN, MISSION, SPACECRAFT, CERES, DWARF PLANET

Dawn Journal | January 31, 2016

Dawn's Sunny-Side Views of Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dear Spellbindawngs,

A veteran interplanetary traveler is writing the closing chapter in its long and storied expedition. In its final orbit, where it will remain even beyond the end of its mission, at its lowest altitude, Dawn is circling dwarf planet Ceres, gathering an album of spellbinding pictures and other data to reveal the nature of this mysterious world of rock and ice.

Ceres turns on its axis in a little more than nine hours (one Cerean day). Meanwhile, its new permanent companion, a robotic emissary from Earth, revolves in a polar orbit, completing a loop in slightly under 5.5 hours. It flies from the north pole to the south over the side of Ceres facing the sun. Then when it heads north, the ground beneath it is cloaked in the deep dark of night on a world without a moon (save Dawn itself). As we discussed last month, Dawn's primary measurements do not depend on illumination. It can sense the nuclear radiation (specifically, gamma rays and neutrons) and the gravity field regardless of the lighting. This month, let's take a look at the other measurements our explorer is performing, most of which do depend on sunlight.

Of course the photographs do. Dawn had already mapped Ceres quite thoroughly from higher altitudes. The spacecraft acquired an extensive set of stereo and color pictures in its third mapping orbit. But now that Dawn is only about 240 miles (385 kilometers) high, its images are four times as sharp, revealing new details of the strange and beautiful landscapes.

Our spaceship is closer to Ceres than the International Space Station is to Earth. At that short range, it takes a long time to capture all of the vast territory, because each picture covers a relatively small area. Dawn’s camera sees a square about 23 miles (37 kilometers) on a side, less than one twentieth of one percent of the more than one million square miles (nearly 2.8 million square kilometers). In an ideal world (which is not the one Dawn is in or at), it would take just over two thousand photos from this altitude to see all the sights. However, as we will discuss in more detail next month, it is not possible to control the orbital motion and the pointing of the camera accurately enough to manage without more photos than that.

Most of the time, Dawn is programmed to turn at just the right rate to keep looking at the ground beneath it as it travels, synchronizing its rotation with its revolution around Ceres. It photographs the passing scenery, storing the pictures for later transmission to Earth. But some of the time, it cannot take pictures, because to send its bounty of data, it needs to point its main antenna at that distant planet, home not only to its controllers but also to many others (including you, loyal reader) who share in the thrill of a bold cosmic adventure. Dawn spends about three and a half days (nine Cerean days) with its camera and other sensors pointed at Ceres. Then it radios its findings home for a little more than one day (almost three Cerean days). During these communications sessions, even when it soars over lit terrain, it does not observe the sights below.

Mission planners have devised an intricate plan that should allow nearly complete coverage in about six weeks. To accomplish this, they guided Dawn to a carefully chosen orbit, and it has been doing an exceptionally good job there executing its complex activities.

Last month, we marveled at a stunning view that was not the typical perspective of peering straight down from orbit. Sometimes controllers now program Dawn to take a few more pictures after it stops aiming its instruments down, while it starts to turn to aim its antenna to Earth. This clever idea provides bonus views of whatever happens to be in the camera's sights as it slowly rotates from the point beneath the spacecraft off to the horizon. Who doesn't feel the attraction of the horizon and long to know what lies beyond?

Another of Dawn's scientific devices is two different sensors combined into one instrument. Like the camera, the visible and infrared mapping spectrometers (VIR) look at the sunlight reflected from the ground. (As we'll see below, however, VIR also can detect something more.) A spectrometer breaks up light into its constituent colors, just as a prism or a droplet of water does when revealing, quite literally, all the colors of the rainbow. Dawn's visible spectrometer would have a view very much like that. The infrared spectrometer, of course, looks at wavelengths of light our limited eyes cannot see, just as there are wavelengths of sound our limited ears cannot hear (consult with your dog for details).

A spectrometer does more than simply disperse the light into its components, however. It measures the intensity of that light at the different wavelengths. The materials on the surface leave their signature in the sunlight they reflect, making some wavelengths relatively brighter and some dimmer. That characteristic pattern is called a spectrum. By comparing these spectra with spectra measured in laboratories, scientists can infer the nature of the minerals on the ground. We described some of the intriguing conclusions last month.