Laura Faye Tenenbaum is a science communicator at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, teaches oceanography at Glendale Community College and writes the "Earth Right Now" blog for NASA's Global Climate Change website.

Earth Right Now | September 26, 2016

Watching our climate 100 miles from shore

Baffin Island, specifically, the largest island in Canada.

“What are we doing all the way out here?” I thought. If I looked out the left side of NASA’s modified G-III aircraft, I could see Canada out the window—Baffin Island, specifically, the largest island in Canada, part of its northeast territory. And if I looked out the right side, I could see the west coast of Greenland. We were pretty much halfway between the two, right in the middle of Baffin Bay, and I was surprised.

At a glacial pace

I went over to where Flight Engineer Terry Lee kept the map of all the scheduled drop positions and stared at it for a while. She’d marked with a green highlighter the places where she’d already released science probes through a tube in the bottom of the plane. (Hahahah, yes! There’s a hole in the plane through which Aircraft eXpendable Conductivity Temperature Depth (AXCTD) probes leave the aircraft to travel 5,000 feet down to the sea surface and then another 1,000 meters into the ocean, sending back data as they go.)

And even though I’d seen this map before, the yellow dots representing scheduled probe drops were right in front of me, out in the middle of the sea, about 100 miles off the coastline. And that confused me because I presumed that this location, this far out at sea, wouldn’t have a layer of fresh water at the sea surface. I figured this far out we’d find salty 3- to 4-degree North Atlantic Ocean Water at the sea surface. So why weren’t we closer to shore where the land ice was melting?I looked out the window as we flew on. Icebergs dotted the seascape. Each one had once been part of a vast ice sheet that’s been around for hundreds of thousands of years. Each one had moved – at a glacial pace, mind you – from the interior, down through one of the many fjords that slice through the Greenland coastline, and finally out to sea, where they would ultimately melt away. The ‘bergs were large, and it was fun to fly over them and look at their perfect whiteness against the stunning blue sea. All of us would gather on one side of the plane as we passed over a ‘berg, and then quickly jump to the other side to look for it again as we passed by it. But even though there were hundreds of icebergs floating around out there, Baffin Bay is vast — more than 250 thousand square miles. So, in the grand scheme of things, the icebergs seemed inconsequential, incapable of affecting the ocean salinity more than a small amount.

Real-time data

I was in the midst of pondering all this, not wanting to bother any of the busy team members, when Oceans Melting Greenland Project Manager Steve Dinardo called me over to the bank of computer monitors where he was working. He motioned for me to trade headsets. After I gave him mine and I put on his, I could hear the AXCTD probe sending its signal to the plane as it descended through the water column, and the noise reminded me of the sound a Wookiee from Star Wars makes.As I was listening, I could see temperature and salinity values arriving in real-time on the monitor. “Wow, no way!” I exclaimed. “That’s insane.” All the way in the middle of Baffin Bay, 100 miles offshore, the ocean was fresher on the surface. I watched the salinity values increase as the probe sank. The temperature profile also reflected a scenario of near-zero-degree water at the surface with 3- to 4-degree ocean water below. That upper layer is Arctic Ocean Water, which is way less salty than the warmer North Atlantic Ocean Water that lies beneath it.

And this is the whole point of NASA’s Oceans Melting Greenland mission—to find out how far that warmer North Atlantic Ocean Water has penetrated. Knowing this will help us measure the quantity and rate at which the warmer North Atlantic Ocean Water is melting the Greenland Ice Sheet.I walked back to look at the yellow dots on the map of the scheduled probe drops one more time. We were as far away from the coast as we would be; the rest of the drops were closer to shore. I wondered how the temperature and salinity profiles in the coastal waters would compare to those from the open ocean.

And the point of the mission flooded my mind again. I looked out the window, across the stretch of Baffin Bay at the Greenland coastline, where groups of icebergs dotted the horizon. In this vast expanse, no one’s done this before, no one knows what this ocean water is like, and we are about to find out.

Find out more about Oceans Melting Greenland.

View and download OMG animations and graphics.

Thank you for your comments.

Laura

TAGS: CLIMATE, OCEANS, MELTING, GREELAND, NASA, JET PROPULSION LABORATORY, JPL

Earth Right Now | September 8, 2016

An ice-tronaut prepares

Greenland is one of the few places that’s harder to get to than outer space

I’m going to Greenland. I told my brother, and he replied, “Oh cool, I’m headed to Ireland.” That’s the typical response, as if Greenland were just some place one could book a ticket to, with commercial airports, and hotels, and restaurants and stuff. But … no, Greenland is different. It’s actually not an independent country, for example. (It’s a territory of Denmark.)

The other response I keep getting is that dumb, corny comment about it not being green. So it seems like the only thing we collectively understand about Greenland is that it’s a place to go and it has a hypocritical name.

But that is just so wrong. My husband and I finally got on the same page this morning when he opened the Google Maps satellite view of Kangerlussauq Airport, where I’m scheduled to land. “Oh,” he said. “It’s a barren dirt strip in the middle of nowhere and nothing.”

At last, an acknowledgement of the truth. The only place that’s harder to get to than Greenland is outer space. I know that sounds funny, but I’m not even kidding. (Okay, okay, Antarctica is also hard to get to, along with the Marianas Trench. Ugh.)

I first became aware of how little we know about Greenland when I was creating NASA’s Global Ice Viewer for our climate website. I found shots from Alaskan glaciers that dated all the way back to the late 1800s for the gallery. Gents with top hats and ladies in bustles with Victorian cameras stood on the ice. But Greenland? Photos taken before the 1980s are extremely rare.

And while most people understand that increased atmospheric temperatures have been melting the ice sheet from above, global warming has also been increasing ocean temperatures. And this means the ocean waters surrounding Greenland are also melting the ice sheet from around its edges.

Which is the reason I’m headed up there with NASA’s Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) campaign in the first place: to measure the temperature and salinity of those unknown waters. See, the fresh water that flows into the ocean from ice melt is about 0 degrees and less dense, so it floats right at the sea surface. The North Atlantic Ocean Water is about 3 or 4 degrees, salty and denser, so it sits right below the fresh melt water. And these two waters don’t really mix much. When the 3- or 4-degree North Atlantic Ocean Water gets in contact with Greenland’s ice sheet, it’s warm enough to melt it.

But no one knows the melt rate yet. No one.

Even though Greenland’s melting ice sheet impacts each and every one of us right now. The rate of ice melt will determine how much sea level rise we’re going to get, 5 feet or 10 feet or 20, everywhere, all over planet Earth, not just in Greenland, but at coastlines near you and me.

This is where that whole NASA “exploring the unknown” theme comes in. Next week, the OMG team (including yours truly) will be in Greenland on NASA’s G-III aircraft. We’ll spend five weeks flying around the entire coastline, measuring the salinity and temperature of the coastal waters by dropping 250 Aircraft eXpendable Conductivity Temperature Depth (AXCTD) science probes through a hole in the bottom of the plane. The reason we’re going in September is that’s the warmest time of the year in the ocean, the ice will reach its lowest extent and we’ll be able to measure as much of the coast as possible. The plan is to repeat the same mission for five years to find out what the melt rate is and how much that rate is increasing.

Am I excited? Yes, beyond. Aside from the science preparation, it took months and months of personal prep. I passed a Federal Aviation Administration medical exam, then got trained in First Aid, CPR, AED, hypoxia, disorientation, survival, and hearing conservation, and then had to buy steel-toed shoes, which are required to fly on that NASA plane. Today, I am psyched beyond belief.

Why else would anyone work so hard to do something? Just like the rest of the team, I hope our work really makes a difference.

TAGS: GREENLAND, EARTH, NASA, JPL, JET PROPULSION LABORATORY, GLOBAL WARMING, OCEANS

Earth Right Now | August 10, 2016

TEDx Talk: Run toward the challenge of climate change. I dare you.

Everyone you admire, everyone who’s accomplished greatness, faced obstacles along the way. Think about it. Everyone. The most impressive athletes, artists or public figures found their way to success by moving through and overcoming roadblocks.

Today, as my morning jog turned into a run and then a sprint, I felt my power and strength as a woman to keep pushing forward. No. Matter. What.

At the entrance to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory where I work, there’s a sign that says “Dare Mighty Things.” The way I see it, that sign is talking directly to me. “I dare you,” it says. Not to try something easy, but to run toward the challenge of climate change with confidence, strength and courage. And now I dare all of you.

TAGS: TEDX TALK, CLIMATE CHANGE, JET PROPULSION LABORATORY, NASA

Earth Right Now | August 2, 2016

Greenland on the edge

Where ice meets water at the bottom of the sea.

A person can look at a thing over and over again before finally seeing it for the first time. That’s how I felt standing in front of an Arctic map at the University of Washington in Seattle. I gazed at the northwest coastline of Greenland, north of Baffin Bay, up where the Canadian Queen Elizabeth Islands come close to Greenland.

Of course I’ve looked at Arctic maps before, from a zillion different angles. Normally I’m the one pointing and explaining. “Look at how small the Arctic area is. It’s a shallow sea, mostly surrounded by continents and islands where sea ice forms and gets trapped,” I say, encouraging folks to get as excited as I am about this remote part of the planet that’s chopped up, spread out and distorted by most maps. But this time, standing next to James Morison, senior principal oceanographer from the University of Washington, I was the one listening, looking closely and being amazed.

We were in the hallway of the Applied Physics Laboratory’s polar science wing, taking a break between Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) science team presentations. The walls were lined with photos of teams out on glaciers, ice drilling equipment, ice sheets of the world and grand ice-covered landscapes. Ice, ice and more ice, and penguins. There were pictures of polar bears and narwhals, too. But Greenland’s jagged coastline had me captivated. The islands, the convolutions, the fjords: phenomenal, mindboggling. I couldn’t take my mind off it.

But the Oceans Melting Greenland team is doing more than looking at maps of Greenland. Way more. “We’re trying to look under the ice,” Principal Investigator Josh Willis told me. “What is the sea floor like under there? What is the interface between where the bottom of the ice sheet reaches out over the seawater and down into the ocean?”

The seawater around 400 meters (1,312 feet) deep is 3 to 4 degrees Celsius (5 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the water floating near the sea surface. And the shape of the sea floor (bathymetry) influences how much of that warm, subsurface layer can reach far up into the fjords and melt the glaciers. The OMG team wants to measure how much of that warm water could be increasing due to climate change.

What will the future hold? Will we see 5 feet of sea level rise … or 10 or 20?

And even though Greenland feels untouched and remote, feels so “Who cares?” we all need to be concerned about its complex coastline and the rapid pace of its melting ice sheet. NASA’s GRACE satellites observed Greenland shedding a couple trillion—with a “t”—tons of ice over the last decade, and the rate of melt is increasing. So that winding coastline and those unfamiliar fjords have already impacted all of us—yes, that means you—undoubtedly, no matter how far away or how far inland you reside.

As each of the dozen or so OMG members took his or her turn updating the team on their most recent topography, temperature and salinity measurements, I noticed a trend. Everyone kept repeating the phrases “never been surveyed before,” “it’s a very tough area,” and “these fjords are so very small, they have no names and have never been visited before.” They are literally exploring these unknown areas in detail for the first time.

My mind drifted off to the edge of that unimaginably complicated winding coastline, that unknown place where ice meets water meets seafloor, where the ice is melting as fast as we can measure. And I had to stop the group to ask why. Specifically, why is it so tough? Why has no one been there before? It turns out this area is difficult to navigate because big chunks of remnant sea ice clog up the water. The crew has to snake in between floating icebergs and weave in and out of the narrow fjords. It’s rather treacherous. And weather conditions can be challenging up there. The other reason this area is so unknown is that the glacier has retreated so recently that the coastline is changing as fast or even faster than we can study it.

Last summer, a small group that included UC Irvine graduate student Michael Wood sailed on the M/V Cape Race deep into some of the most jagged areas around southeastern Greenland, which, according to Co-Investigator Eric Rignot, is the “most complex glacier setting in Greenland.” After more than 7,871 kilometers (4,250 nautical miles) and more than 300 Conductivity, Temperature Depth (CTD) casts, the first bathymetric survey was completed.Over the next five years, OMG will measure the volume of warmer water on the continental shelf around Greenland to figure out whether there is more warm water entering the fjords and increasing ice loss at the glacier terminus.

Here are some details about the OMG plan:

- Every year for four years, survey glacier elevation near the end of marine-terminating glaciers around Greenland’s coastline using NASA’s airborne synthetic aperture radar altimeter GLacier and Ice Surface Topography INterferometer (GLISTIN-A).

- Every year for five years, deploy 250 Aircraft eXpendable Conductivity Temperature Depth (AXCTD) probes to measure temperature and salinity of the waters around Greenland from one of NASA’s G-III aircraft.

- Use a ship with multi-beam sonar to measure bathymetry of the seafloor up very close to the extremely jagged coastline of Greenland, as well as a small vessel with a single beam going up into small places, driving up fjords and getting as close to glaciers as is safe.

- Collect gravity measurements from small planes in Northwest, Southeast and Northeast Greenland to help map the sea floor in places the ships cannot go.

Find out more about Oceans Melting Greenland.

View and download OMG animations and graphics.

Thank you for your comments.

Laura

Oceans Melting Greenland is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.?

TAGS: ICE, SEA, GREENLAND, SOUTHWESTERN COASTLINE

Earth Right Now | July 14, 2016

Shuffle and flow: Where does carbon come from, and where does it go?

The average amount of carbon dioxide in Earth’s global atmosphere is 400 parts per million (ppm).

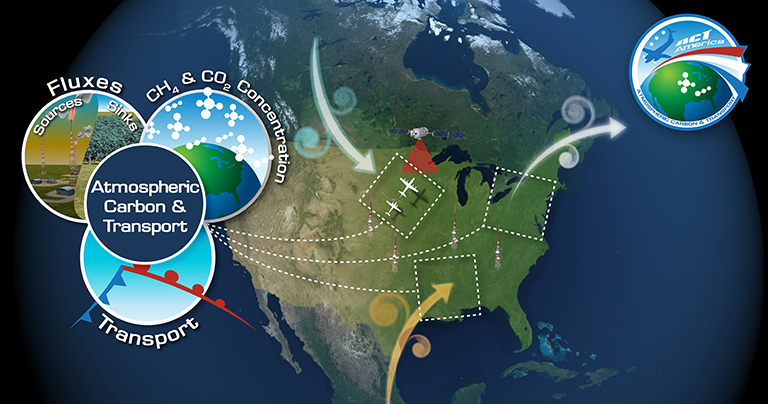

The average amount of carbon dioxide in Earth’s global atmosphere is 400 parts per million (ppm), but according to Ken Davis, Atmospheric Carbon and Transport - America (ACT-America) principal investigator, areas near agriculture like cornfields can consistently run about 10 ppm lower in the summertime. That’s because terrestrial ecosystems like trees and corn suck about a quarter of our carbon dioxide emissions out of the atmosphere.

Thank you, trees and corn.

But wouldn’t you like to know exactly where this is happening, and by how much? Does the amount of carbon dioxide taken up by farms and forests change across seasons, across weather patterns? And even more important, will these ecosystems still be able to continue pulling our carbon pollution out of the atmosphere for us 50 years from now, especially if our climate changes unfavorably for these biological systems? Will dead trees start releasing carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere? It’s as if the forests and farms are “Get Out of Jail Free" cards and we’re not sure for how long the free pass will be good.

See, scientists have been measuring carbon dioxide and methane on a global basis. But we’d like to understand the mechanisms that are driving biological sinks and sources regionally. And we’d like to measure these greenhouse gases so that we can know if and when we’ve succeeded in reducing our emissions.

Davis explained that right now, most of our knowledge about regional sources of methane and carbon dioxide comes from a ground-based network of highly calibrated instruments on roughly 100 towers across North America. Yet being able to understand the regional sources and sinks of these two greenhouse gases is crucial to being able to predict and respond to the consequences of a changing climate.

“We don’t have all the data we need? That’s unbelievable,” I said, shocked. How is that even possible in 2016?” But Davis kept repeating: “No, we definitely don’t have enough data density.” Indeed, we take our data for granted, even as we continue burning fossil fuels.

So on July 18th, Davis and his team will head out to the first of three study areas for a two-week stint. These three regional study areas were chosen to represent a combination of weather and greenhouse gas fluxes across the U.S. The Midwest has a lot of farms and therefore has an agricultural signal. It’s also the origin point of cyclones. The Northeast forests are different than the Southern coastal forests, which will give us both types of data. The Southern coastal weather, storms and flow off the Gulf of Mexico are unique, and there’s oil and gas development in both the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions. This means that between these three study areas, the team will be able to observe a wide range of conditions.

In addition to measuring regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide and methane, ACT-America is planning to fly on a path right underneath NASA’s OCO-2 satellite to measure air characteristics, provide calibration and validation and make OCO-2’s data more useful. The mission will also fly through a variety of weather systems to find out how they affect the transport of these greenhouse gases.

Davis told me he’s “excited to fly through cold and warm fronts and mid-latitude cyclones to find out how greenhouse gases get wrapped up in weather systems.”

Find out more about ACT-America here.

Thank you for reading.

Laura

ACT-America? is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.

TAGS: SHUFFLE, FLOW, CARBON, ATMOSPHERIC CARBON

Earth Right Now | July 5, 2016

How NASA prepares future climate scientists for careers in the sky

NASA's Student Airborne Research Program trains future climate scientists.

We receive a lot of questions, especially from students, asking us for information about how to get a job at NASA. Well, there’s more than one way to get hired here. But one of the most awesome methods we have of training young scientists and preparing them for potential hire here (or a great position anywhere) is by recruiting university undergraduates for our Student Airborne Research Program (SARP).

SARP is our eight-week summer program for college seniors with academic backgrounds in engineering or physical, chemical or biological sciences and an interest in remote sensing. We select about thirty students based on their academic performance, their interest in Earth science and their ability to work in teams. These students receive hands-on research experience on NASA's DC-8 airborne science laboratory. Yup, they get to fly on a modified NASA plane out of NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center, in Palmdale, Calif., where they help operate instruments onboard the aircraft and collect samples of atmospheric chemicals.

Did I already say “awesome”? Oh right, I did. Well, I’ll say it again: Awesome.

Many students apply hoping to gain more research experience for graduate school. The whole air sampling team, which is exactly what it sounds like, collects air from around the plane in canisters as it’s flying through different locations and altitudes at different times. The air enters the plane from the outside through an inlet, a pipe sticking out of the plane. The student scientists open the canisters, allowing air from outside the airplane to suck into the can. Then they take the air samples back to the lab at the University of California, Irvine, for analysis and interpretation.

SARP students analyze the air samples for hydrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane, hydrocarbons, nitrates, oxygenates and halocarbons. Research areas include atmospheric chemistry, air quality, forest ecology and ocean biology.

Once the airborne data has been collected and analyzed, the students make formal presentations of their research results and conclusions. Over the past seven years, the program has hosted 213 students from 145 U.S. colleges and universities. And this year we look forward to helping our latest crop of SARP students gain research experience on a NASA mission, work in multi-disciplinary teams and study surface, atmospheric and oceanographic processes.

Find out what SARP students thought about their experience here.

Find out more about SARP and other Airborne Science Programs here.

Thank you,

Laura

SARP is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.

TAGS: NASA, CLIMATE, FUTURE, CAREERS

Earth Right Now | June 20, 2016

A sea slug changed my life

At 8 p.m. after a long day of work in the Houston humidity, Derek Rutavic, manager of the NASA Gulfstream-III that will head back to Greenland this fall, and I were in the back of the plane singing One Direction’s "Drag Me Down" over the high frequency radio system. It was stifling hot, getting dark and we were tired and hungry.

But Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) Principal Investigator Josh Willis and Project Manager Steve Dinardo, too busy to take off their sweaty fire retardant flight suits, were troubleshooting electronics at two racks of computers, and they’d asked Rutavic to get on the headset to find out if the headset noise was interfering with the high radio frequency data signal the ocean science probes were sending back to the plane. Rutavic sat on an empty science probe container, while I lounged on one of the sofas singing along in awe of the amount of hard work this team was putting in.

We’d been up early, flown multiple test flights, worked through lunch. And all of this after days and days of maintenance, and weather delays, and more hard work after more hard work. Earlier in the day, NASA T-38 supersonic jet pilot Bill Rieke flew mind-bogglingly close to the G-III to photograph the science probe deployment and determine if the technique of launching the probes through a hole in the bottom of the plane would succeed. And yes, it did. But that success merely signaled the OMG team to continue working.

And I understood exactly why this team kept going, kept moving, kept pushing on into the evening, regardless of being tired and hot and hungry. I knew exactly why they decided to keep working on the challenge. They chose to push through because they’d found something to care about, and that's always more important than our difficulties and problems. When we focus on what we really care about, we get busy doing something, even in the face of trouble. And that’s how science works.

Lessons from a sea slug

I first learned to care about the natural world around me during my junior year in college. I was in an oceanography course and we were studying sea slugs. (Yes, sea slugs.) A sea slug changed my life. Before then, I’d been, like many people, disengaged and uninterested in science. In third grade, someone came to our classroom and told us we could be the first female astronaut, and I remember thinking, “No, I couldn’t, not me.”

And now? Even though I have a job at NASA, I still feel like I don’t belong in the world of science. I feel more comfortable around athletes and artists than I do with a bunch of Ph.D.s. Maybe it’s some poorly defined stereotype that I’ve somehow bought into or some preconceived notion of how someone who does science is supposed to behave.

But those sea slugs taught me that I cared more about the natural world than I cared about the struggle of not fitting in or the challenge of the work. They appeared so delicate, small and defenseless, and I identified with that. They helped me feel connected. Noticing them forced me to wonder what else I’d start to notice if I slowed down enough to pay attention. And that connection to the natural world helped me stay committed to science, even when it was hard, even when there were problems, even when I felt like running away.

Sure, scientific experimentation, just like much of real life, includes problems, troubles, obstacles and difficulties almost every day. And while it’s true that someone, somewhere has to troubleshoot something every step of the way, we can also be excited about the effort. The OMG team understands that problems and hard work are not the exception, they are the norm. They are part of accomplishment. And it’s totally possible to thrive on these difficulties and challenges.

Look, we could be setting the world on fire right now, not by burning fossil fuels, but by our burning desire to understand our environment. Because the whole point of this experimental mission is to find out how quickly the warmer waters around Greenland are melting the second-largest ice sheet on the planet. It’s major; it’s dire; it’s intense. It’s one of the most important issues of our time.

And sitting there in the back of that plane made me think about how we, as individuals and as a society, have to find something in this world to care about. We have to find something in this world that is more important than our challenges and problems.

And you? I hope you decide to find something to care about. I hope you find something that’s important enough that you’re willing to push through your struggles, your fears and your problems to just do the work.

Find out more about Oceans Melting Greenland.

View and download OMG animations and graphics.

Thank you,

Laura

Oceans Melting Greenland is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.

Earth Right Now | June 7, 2016

OMG: Testing the waters to see how fast Oceans are Melting Greenland

We know more about the moon and other planets than we do some places on our home planet. Remote parts of the world ocean remain uncharted, especially in the polar regions, especially under areas that are seasonally covered with ice and especially near jagged coastlines that are difficult to access by boat. Yet, as global warming forces glaciers in places like Greenland to melt into the ocean, causing increased sea level rise, understanding these remote places has become more and more important.

This past spring, Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) Principal Investigator Josh Willis led a team of NASA scientists to begin gathering detailed information about the interface between Greenland’s glaciers and the warming ocean waters that surround them. The next step in accessing this extremely remote region involves dropping a series of Airborne Expendable Conductivity Temperature Depth, or AXCTD, probes that will measure ocean temperature and salinity around Greenland, from the sea surface to the sea floor. With this information, they hope to find out how quickly this warmer ocean water is eating away at the ice.

Since no one has ever dropped AXCTDs through a tube at the bottom of a modified Gulfstream-III, the OMG team headed to Ellington Field Airport near NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, for a test drop into the Gulf of Mexico. I went along for the ride.

"In position!"

Expert NASA T-38 pilot Bill Rieke executes his flight plan to rendezvous with the Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) scientists and engineers aboard NASA’s modified Gulfstream-III at “drop one.” As soon as photographer James Blair is ready with his high speed and high definition cameras, he calls out “In position!” from the supersonic jet to the team in the G-III over Very High Frequency (VHF) radio.The money shot

It’s up to Derek Rutovic, G-III program manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, to visually inspect the release of the AXCTD to make sure it does not impact the plane and then to see that the parachute opens. The first test drop was released while the plane was flying at a height of 5,000 feet and a speed of 180-200 knots.Temperature and salinity

Alyson Hickey and Derek Rutovic prepare the AXCTD tubes for deployment. After these test flights are complete, the mission heads up to Greenland this fall, where the AXCTDs will measure temperature and salinity around Greenland to make a detailed analysis of how quickly the warmer waters around Greenland are eating away at the ice sheet.3, 2, 1 ... drop!

G-II pilot Bill Ehrenstrom calls out “Three, two, one, drop!” over the Very High Frequency (VHF) radio channel to signal Rocky Smith, who then pushes the AXCTD tube through a hole in NASA’s modified Gulfstream-III. Rocky then announces, “AXCTD is clear.”AXCTD sails down

Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) Project Manager Steve Dinardo and OMG Principal Investigator Josh Willis wait for a radio signal as the AXCTD sails down through the air to indicate it’s arrived at the sea surface. Once it hits the sea surface, it releases its probe, which travels through the ocean to the sea floor and sends ocean temperature and salinity data up to the team in the aircraft above, who monitor the data in real time.The flight path

Both aircraft must execute a complex flight path, which involves filming two precision AXCTD test drops minutes apart.Details, details, details

Find out more about Oceans Melting Greenland.

View and download OMG animations and graphics.

Thank you for your comments.

Laura

Oceans Melting Greenland is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.

TAGS: OMG, TESTING, WATERS, OCEANS, MELTING, GREENLAND

Earth Right Now | April 20, 2016

Game on, climate change! This Earth Day, be confident

Cimate change news is intense. Ice caps are melting, the fire season lasts all year long; we have epic storms plus record-breaking floods, droughts and cyclones.

And this year will probably be the Hottest. Year. Ever.

When I interact with the public, I’m bombarded with questions such as “Are we all going to die?” and “How soon will humans go extinct?”

Happy Earth Day, everyone (wipes brow, rolls eyes).

Yet, when I wake up in the morning I'm excited to come to work. I'm energized. I’m amped, really amped. As in, kicking-butt-and-taking-names amped. Why? Because global warming is the greatest challenge of our lives, and challenge is what drives us. Challenge provides us with opportunity, challenge forces us to grow, challenge opens the way for amazing achievement. Challenge is exciting. Without challenge, without struggle, without discomfort, no one would ever advance.

So, when someone gets in my face and is super negative, I try to stay powerful, strong and confident. I tell myself that pressure is okay and I'm going to keep moving no matter what. Because I care about this planet so much that I choose to make a difference.

Yes, carbon dioxide levels are high and increasing rapidly. Yes, future generations will have some extraordinarily difficult challenges to deal with. But denial, avoidance and helplessness aren’t solutions. Can you imagine if we NASA peeps just sat there saying “Oh no, that’s too hard” when faced with huge obstacles? Are you kidding me? Come on! You think it’s easy to build science instruments on satellites and launch them into space? You think it’s easy to measure glaciers melting around the edges of Greenland, or the condition of coral reefs in the Pacific, or plankton blooms across the North Atlantic, or conduct eight field research campaigns in one year?

When the going gets tough—and it does, almost every day—we don’t just stop. We keep working. We know that no successful person got As on every test and that failure and struggle are part of accomplishment. We know that grit and determination will get you everywhere!

In this blog, I write about ocean pollution, sea level rise, climate change and decreasing biodiversity not to scare you, but to empower you, so we can make a difference—you and I, together. Someone reading this blog entry might be the creator of a new breakthrough technology, and then there will be a whole new reality.

So, when you think about the challenge of climate change this Earth Day, consider the possibility of welcoming that challenge. Our shared story could be a story about not giving up, about looking forward to growth, about saying, “Game on.”

Find out more about NASA earth expeditions here.

Join NASA for a #24Seven celebration of Earth Day.

Thank you for caring enough to make a difference and for being powerful in the world.

Laura

TAGS: CLIMATE, CHANGE, EARTH, DAY, HOTTEST, GLOBAL, WARMING

Earth Right Now | April 1, 2016

Sorrow and excitement

Hey, readers: Our team reads your comments. We share them at our meetings. Sometimes they make us laugh, or sigh, or even scratch our heads.

We see that you see us. Yay for connecting!

And this is how I know you’ve noticed NASA’s latest airborne campaign, where NASA scientists fly a bunch of NASA instruments on a NASA airplane to study more details about Earth. Cool, right?

Lately, we’ve been flying around the edge of Greenland collecting radar data about how much its glaciers are melting into the sea. And the most common comment we get goes something like “Wheee! Let’s go. Take me with you.” When I told a friend about the possibility of joining the team in the field, she exclaimed, “All expenses paid?”

HAHAHA … no. As if a NASA expedition to Greenland is like a resort vacation instead of a giant heaping pile of hard work.

“When I looked down at the rivers of ice running into the ocean, it was shocking to think about the effects of rising sea levels as far away as California or Antarctica,” said Principle Investigator Josh Willis, two days after returning from his first trip to observe this pristine part of our planet as it melts into the sea and goes bye-bye. “Yet, I had a blast.” Because even though we all probably have many complex emotions about climate change, ice mass loss and sea level rise, we can still simultaneously feel super duper stoked about the chance to fly over the glaciers of Greenland in a freaking NASA plane. “The mountains, the ice, the water and the ice in the water are incredibly striking even though it’s lonely to see it disappearing at the hands of human activity,” he told me.

Yes, emotions are weird, and yes, there’s an awkward contrast or odd juxtaposition between feeling both thrill and grief at the same time.

But that’s life, I guess.

So just in case you’re still envisioning a champagne-swilling, caviar-scoffing, gangsta, hip-hop music video scene, here are a few things that might surprise you about the kind of major effort it takes to get on board NASA’s G-III plane and join the Oceans Melting Greenland field campaign:

Kick booty in a fire-resistant flight suit

So, you think you’d kick some booty in one of these flight suits? Oh, yeah. Totally. Well, so do we. Would you kill to have one? But the real reason the pilots think they’re so fab is because they’re fire-resistant. They. Resist. Fire! With racks and racks of science equipment wired with electrical cables, the crew has to be extra careful about fire on the plane. So wearing one of these flight suits is required.

A load of gas and no mistakes

A trip to Greenland sounds all romantic ‘n’ stuff, but operating a science instrument aboard a flying science lab on a six-hour flight every day is hard work. Just check out these flight paths. According to Project Manager Steve Dinardo, “You get a full load of gas and no mistakes.” Notice the flight path zigzags across the complicated coastline of the entire island. That’s because global warming of Earth’s atmosphere is melting the top of the ice sheet. But, aha! The ocean water around Greenland is even warmer than the air. That warm water is busy melting the glaciers from around their edges, hence the name, Oceans Melting Greenland, which will find out exactly how much of this melting is going on.

Instruments, instruments and more instruments. And did I mention some serious training?

The NASA modified G-III aircraft is … modified. (Did you notice the word “modified”?) What modified means is the plane has holes in it so experimental science instruments can stick out. And more scientific instruments are attached in, under and onto the plane in all sorts of configurations. To get to fly on this baby, you’d better have some training. Yep, some serious training: Safety training, first aid training, survival training. You get the idea.

Keep warm, in style

I can work the runway like a glamazon in this red coat, but it’s rated for survival in 50 degrees below zero. I said survival. In case of emergency. Does this sound like your all-inclusive vacation package now? With a survival coat? And there’s a survival vest too, with a beacon attached, and food rations, a pocketknife tool set, fishing gear, first aid supplies, a radio and a laser pointer for playing with cats—oops, I mean for signaling emergency and attracting rescue. The thing weighs about 20 pounds. Everyone on the plane has one of these puppies, and you’d better believe they know how to use it. If there’s a problem, the team would have to survive three to five days out in the wilderness until they're rescued. I don’t mean to scare you, but at NASA, when we say we care about safety, we’re not messing around.

“It’s not a triumph of human achievement that we’re melting the ice sheet,” said Willis. “When you see how huge these glaciers are and this huge chunk of this ice sheet disappearing into the ocean, it’s almost incomprehensible even when you see it from 40,000 feet.”

Wheee.

Find out more about Oceans Melting Greenland here.

View and download an OMG poster/infographic here.

Thank you for your comments.

Laura

Oceans Melting Greenland is part of NASA Earth Expeditions, a six-month field research campaign to study regions of critical change around the world.

TAGS: GREENLAND, OCEANS, MELTING, GREENLAND, OMG