Classroom Activity

Looking for Life

Overview

In this activity, students will use research to develop an operational definition of life and then use the fundamental criteria for life to examine simulated extraterrestrial soil samples for signs of life.Materials

Management

- Prior to teaching the lesson, locate an outdoor area that contains a variety of living and nonliving things for students to investigate. If an outdoor area is not available, gather images of a variety of living and nonliving things.

- The day ahead of teaching the lesson, mix a batch of each soil sample (enough for the class) and store in airtight containers. Humidity will inactivate the yeast and cause the effervescent tablets to lose their fizz.

- Right before the lesson pour samples into jars for each group

- Be sure the water is not too hot. Yeast do well with warm tap water (about 50 C).

Background

We can usually recognize whether something is alive or not alive. But when scientists study tiny samples or very old fossilized materials, the signs of life are not always clear. And when investigating material that may have been alive at one time, the science is more difficult. So scientists must establish criteria to use in their research. Here are the five signs scientists use as the established fundamental criteria for life:

- Locomotion

- Metabolic processes that show chemical exchanges, which may be detected in some sort of respiration, or exchange of gases or solid materials

- Some type of reproduction, replication or cell division

- Growth

- Reaction to stimuli

During the Viking Mars missions, tests for life were based on the idea that life would cause changes in the air or soil in the same way it does on Earth. The Viking tests did not detect the presence of life on Mars, nor would they have detected fossil evidence of past life on Mars or life that is different from that on Earth. Recent Mars missions have yielded a number of findings that shape the way we search for evidence of past life on the Red Planet. The Curiosity rover has determined that Mars was once potentially hospitable for life and had liquid water flowing on the surface. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has obtained evidence that liquid water still flows seasonally on Mars. And the Mars 2020 mission will conduct further investigation regarding the Red Planet's habitability and astrobiology, the study of life on other planets.

Procedures

Part 1

- Ask students, "How do you know if something is alive?" and discuss the criteria students come up. Provide counterexamples as appropriate.

Example: Consider a bear and a chair— they both have legs, but one can move on its own and the other can't; therefore, independent movement might be one characteristic that indicates life. Not every living organism needs legs or roots. But they do need a mode of locomotion or a way to get nutrients. Also, the bear breathes and the chair does not, another indication of life. Or consider a tree and a light pole. We know that a light pole cannot reproduce — it is made by humans — and we know that the tree makes seeds that may produce more trees. The tree also takes in nutrients and gives off gasses and grows. The light uses electricity and gives off light, but it is strictly an energy exchange and there is no growth or metabolic processes. - Distribute Criteria for Life Log Charts, one per student or pair. Tell students they are to go outdoors and locate five living organisms and log them on their chart.

- Return to the classroom and make a large chart that includes all of the students' findings.

- Ask students to explain why they deemed each object to be alive.

- Guide students in summarizing their findings into criteria that can be used to determine the presence of life. List criteria across the top of the class chart. Students might not list all the fundamental criteria for life. They might state the more obvious signs, like methods of locomotion, but guide them toward including the five criteria for life.

- Have students check off on their charts which of the 5 signs of life their living things exhibit. Discuss that it may be difficult to observe some of these in a short period of time, but inference from experience and prior knowledge can be made.

Part 2

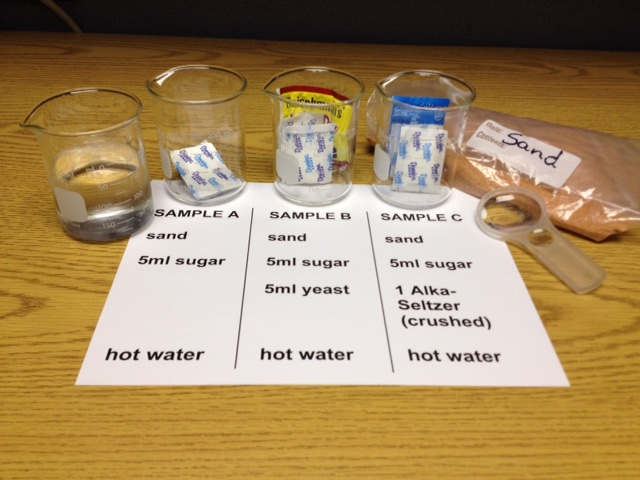

- Just before class, prepare jars of soil samples for student groups of three to four students.

- Place 50 ml of sand in each jar. (You will need 3 jars per team.)

- Add 5 ml of sugar to each jar. Label one jar in each set of 3 “A” and set aside.

- Add instant active dry yeast to the second jar in each set of 3 and label these jars “B.”

- Add a powdered fizzing antacid tablet to the remaining jars. Label these jars “C.”

- Give each group a set of three jars, a hand lens and Data Chart I.

- Explain to the students that each team has been given a set of soil samples. No one knows if there is anything alive in them. The assignment is to make careful observations and check for indications of living material in the samples based on the fundamental criteria for life.

- Ask students to observe all three samples for signs of life. They can smell and touch the samples, but not taste them. Encourage students to put a few grains on the circles on Data Chart 1 and observe them with a hand lens. Students should then record their data.

- Give each group a cup of water. (Use hot tap water, about 50 C, for the best results. Do not kill the yeast.) Ask students to pour the water so that each sample is covered with water.

- Repeat Step 2 and record the data on Data Chart II. Students should look for and record differences caused by adding water. After recording the first observations, have students go back and observe again. (After about 10 minutes, Sample B will show even more activity. Leave it for several hours or overnight and reproduction will be obvious.)

- Discuss which samples showed indications of activity (Samples B and C). Does that activity mean there is life in Samples B and C and no life in Sample A? Are there other explanations for the activity in either B or C? (Note: Samples B and C exhibit a chemical reaction; Sample C activity stops; Sample B sustains long term activity; Sample A is a simple physical change in which sugar dissolves.)

- Determine which sample(s) contain life by applying the fundamental criteria for life.

- Tell students that Sample B contained yeast and Sample C contained an effervescent antacid tablet. Discuss how scientists could tell the difference between a nonliving chemical change (fizzy antacid) and a life process (yeast) which is also a chemical change.

- Discuss which of the criteria for life would identify yeast as living and fizzy antacid as nonliving.

Discussion

- Besides Mars, where else might there be life in our solar system?

- Is it possible that there is life on a planet orbiting another star?

- How do scientists look for life when they can't visit another world themselves?

Evidence of respiration, amino acids, etc.

Assessment

This activity may be assessed by examining student documentation of living things in the school yard and samples. Students should be able to state the fundamental criteria for life and describe how each is observable.Extensions

- Learn about astrobiology, the search for life on other worlds

- "Exoplanets and the Search for Habitable Worlds" article and lesson

- Learn about exoplanets, planets outside our solar system

- Keep track of the current exoplanet discovery count

- Download the Exoplanet Travel Bureau posters

- Learn about exoplanet detection methods

- Ask an astrobiologist

- Life in the Extreme Activity Cards

- Astrobiology Science Learning Activities for Afterschool