Southern Exposure | November 14, 2015

Layover on an Antarctic Journey Part I

On Thursday evening, I boarded Qantas Flight 18 from LAX to Sydney, Australia. The Boeing 747 departed just after midnight and landed in Sydney on Saturday morning. I had a 9.5 hour layover in Sydney, so I went through customs in Australia, checked my large carry-on bag at the airport, and took the train to Circular Quay (the Aussie pronunciation is Circle Kay). There, I wandered around the famous Sydney Opera House and Royal Botanical Gardens.

See the slideshow above for photos of my adventures around Sydney.

After a nice afternoon, I boarded my evening flight to Christchurch, New Zealand. The flight landed around midnight, and after going through customs in New Zealand, where I had to convince the agents that my JPL hardware would not harm sheep, I finally arrived at my hotel at 1 a.m. Door-to-door travel time was around 32 hours. I was on empty and enjoyed a short night’s sleep before waking up to go to the Clothing Distribution Center the following morning. Stay tuned for my next post!

TAGS: STO-2, ANTARCTICA, MCMURDO, ASTRONOMY, ASTROPHYSICS, BALLOONING

Southern Exposure | November 12, 2015

Introduction to the Ice

Welcome! This blog is intended to provide a behind-the-scenes look at life and work as a researcher in Antarctica. My trip begins tonight and I intend to update this blog with all of my interesting experiences as I travel to the "ice" as well as a discussion of the science we intend to do and the technology we have engineered to do it!

Traveling to Antarctica is what I imagine the experience of visiting a foreign planet would be like. With no plant life and a very arid climate, the continent feels surreal and unlike anything I have ever sensed elsewhere on Earth. I look forward to sharing my journey as we launch the Stratospheric Terahertz Observatory II (STO-2) from Willy Field!

Please feel free to contact me through my Science and Technology Personnel website with any questions and I will try my best to address them in future blog posts. As an added incentive to encourage questions from my readers, I will write postcards to the first 20 individuals and all K-12 classrooms who email me a question with their name and address.

My first trip to the ice was for STO's maiden voyage in the Antarctic spring and summer of 2011-2012. After my first trip, I learned that people have a lot of questions and misconceptions about the continent, so I want to start by addressing some of the most commonly asked questions.

First of all, geographically Antarctica refers to the southern-most continent on the planet. It is spring right now in the Southern Hemisphere and at McMurdo Station the sun is out 24 hours a day. The last sunset was Oct. 23, 2015, and the next sunset will be February 21, 2016. At McMurdo, we stay on New Zealand time (PST plus 21 hours) since it is the closest country to us.

The Arctic refers to the northern polar region. The Antarctic refers to the southern polar region.

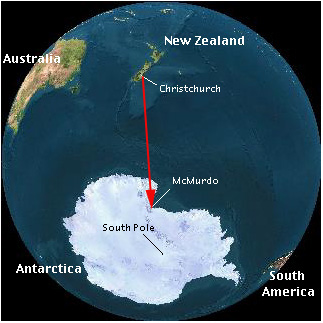

Antarctica does not belong to any one country. Instead, it is governed by a treaty among 53 countries that preserves the continent for scientific exploration and bans any military activity. Currently, 30 countries operate bases for research. The United States has three main bases and two smaller outposts. I will be stationed at McMurdo, which has its closest approach from New Zealand and is by far the largest base on the continent with more than 100 buildings and about 1,000 people during the summer season.

In order to get to McMurdo, everyone flies commercially to Christchurch, New Zealand. (Another frequent misconception is whether I fly through Chile to get to Antarctica. There is a in fact a U.S. station on that side of the continent called Palmer Station, but it is not where I will be going.) The day after we arrive in Christchurch, also referred to as CHC (pronounced: cheech) because of the airport code, we are issued Extreme Cold Weather (ECW) gear from the Clothing Distribution Center (CDC). The CDC is where we pick up the big red jackets for which the the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) is famous. I loved my "big red" last time and returning it upon redeployment was such sweet sorrow. (No, we do not get to keep any of this stuff.) I am looking forward to our re-acquaintance!

Ice flights usually occur the day after visiting the CDC. If I am lucky, when I show up for my flight, it will be a C-17 plane. If not, I will fly an LC-130. What is the difference? A C-17 is basically a first-class cargo plane. It has jet engines and can reach Antarctica in around five hours. The flight crew installs real seats, and it has a bathroom, too! Although I have never been unlucky enough to fly a LC-130, my understanding is that plane is more like the Ryan Air of cargo planes -- you just sort of strap in wherever and hope for the best. If one needs to use the restroom while in flight, there is a privacy screen with a bucket. Since these planes do not have jet engines, the trip takes a whopping eight or nine hours! Similarly, weather conditions in Antarctica are unpredictable. It is possible that the flight will get canceled after all the passengers get to at the airport. Even worse is the "boomerang," in which we fly all the way to the continent, cannot land, and have to return to CHC. That means 10, or even 16 hours in flight and then you have to try again at the next available opportunity. Is anyone still interested in stowing away in my luggage as science cargo?

Upon my arrival in McMurdo, I will participate in a scientific balloon mission to launch a telescope into the stratosphere (the second major layer of Earth's atmosphere) to study how stars are born. This is the poor man's version of going to space. We will commute daily from McMurdo to an airfield located about eight miles away on the Ross Ice Shelf. We go to Antarctica for the polar vortex that sets up around the summer solstice. (There is also one in the winter, but flights are only conducted in the summer.) Each rotation around the continent lasts about 14 days, and if we launch early enough, we may continue for another rotation. The wind patterns have set up as early as December 5, but usually are not ready until after December 15. Last time I was there, the vortex was not ready until December 25, so unfortunately I do not yet know our launch date. Dear readers will have to stay tuned!

So how long will I stay down there? It really depends on when we are able to launch. Last time, because of the unusually late set up of the polar vortex and strong ground winds, STO did not launch until January 15. More factors, such as available flights back and weather conditions for planes to take off, play a role. In short, I am preparing to stay a while.

Questions? Topics related to Antarctica or STO-2 you would like to see addressed? Please email me!

TAGS: STO-2, ANTARCTICA, MCMURDO, ASTRONOMY, ASTROPHYSICS, BALLOONING

JPL | December 15, 2010

Lunar Eclipse, the Moon's Interior, and the Holy GRAIL

In addition to the awesome views they offer, lunar eclipses have always provided scientific clues about the moon's shape, location and even surface composition. Although there will continue to be opportunities for observers to examine and reflect on fundamental concepts about the moon, such as its origin and interior structure, more modern tools are aiding these observations.

When it comes to understanding what a moon or a planet is made of remotely -- short of touching it or placing seismometers on its surface or probes below the surface -- classical physics comes to the rescue. By measuring the magnetic and gravitational forces that are generated on the inside and manifested on the outside of a planet or moon, we can learn volumes about the structure of its interior.

A spacecraft in the proximity of the moon can detect these forces. In the case of gravity, the mass of the moon will pull on the spacecraft due to gravitational attraction. If the spacecraft is transmitting a stable radio signal at the time, its frequency will shift by an amount exactly proportional to the forces pulling on the spacecraft.

This is how we weigh the moon and go further by measuring the detailed distribution of the densities of mountains and valleys as well as features below the moon's surface. This collection of information is called the gravity field.

In the past, this has lead to the discovery mascons on the moon, or hidden, sub-surface concentrations of mass not obvious in images or topography. If not accounted for, mascons can complicate the navigation of future landed missions. A mission, human or robotic, attempting to land on the moon would need to have a detailed knowledge of the gravity field in order to navigate the landing process safely. If a spacecraft sensed gravitational pull higher than planned, it could jeopardize the mission.

The Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission, scheduled to launch in September, is comprised of twin spacecraft flying in formation with radio links between them to measure the moon's gravity field globally. This is because a single spacecraft with a link to Earth would be obstructed when the spacecraft goes behind the moon, leaving us with no measurement for nearly half of the moon, since the moon's far side never faces the Earth. The GRAIL technique may also reveal if the Moon has a core with a fluid layer.

So as you go out to watch the lunar eclipse on the night of Dec. 20, think about how much we've learned about the moon so far and what more we can learn through missions like GRAIL. Even at a close distance from Earth, the moon remains a mystery waiting be uncovered.

JPL | July 29, 2010

Confessions from Comic-Con

I've been standing in line next to a green monster for more than an hour. This might sound like a bad situation, but the monster is actually a rather nice human in body paint and stunning, neon-green contact lenses. This is my fourth time at Comic-Con -- San Diego's annual gathering of all things geeky (some people call it "The Nerd Prom"). Lines to get into the various panels are a regular part of the program, especially now that attendance has swelled to well over 100,000. The lines here can actually be kind of fun -- people sit down on the carpeted floors, read comics, enjoy all the costumed creatures and superheroes, and chat with like-minded friends.

Standing in line to see one of Comic-Con's regular heroes -- Joss Whedon, the creator of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" and director of the new "Avengers" movie -- I discover that a couple of my line companions and I are even more like-minded than I thought. They also work at JPL in Pasadena. One is an engineer working on the next Mars rover, Curiosity (although he didn't call the rover Curiosity -- like many engineers, he's accustomed to using its original acronym, MSL, which stands for Mars Science Laboratory). The JPL connection doesn't stop there. My new JPL friends just came from a panel that included Kevin Grazier, who works on NASA's Cassini mission to Saturn -- he's also science advisor for "Battlestar Galactica" and "Eureka."

It's no surprise that there's crossover between science and science-fiction geeks. Many of the astronomers I work with at JPL were inspired to go into astronomy by sci-fi shows like "Doctor Who" and "Star Trek." Science fiction and superhero stories take us to imagined worlds, while scientists and engineers take us to real worlds that can sometimes be even more surprising and exotic. At Comic-Con, the excitement about what we can do with our minds is more than a buzz, it's a roar.

Mingling with all of us humans (or people like me who still haven't figured out a good costume) are robots and creatures from many worlds. I spot bands of Cylons and stormtroopers, Bender the robot from "Futurama," Sookie Stackhouse from "True Blood," and many more. Superheroes stride proudly through the crowd, stopping about every two feet to pose for more pictures. There are numerous "Wonder Womans." I was particularly impressed by one, a gray-haired woman probably in her 60s, who looked fantastic in her star-spangled short shorts and red vinyl boots. And of course there are lots of zombies. (If there's one thing that became very clear to me this year, it's that vampires are on their way out and zombies are back in.)

I also chat with several artists and writers, and sit in on a few panels teasing us with upcoming storylines for TV shows. In the end, I am left with the impression that there are still so many stories to tell, so much left to explore. The Comic-Con experience inspires me in the same way that astronomy conferences do. We're all pushing into the unknown in unique ways. It would be cool, though, if astronomers also dressed up as what inspires them during their conferences. I'd love to come across a globular cluster of human stars parading across the exhibit-hall floor.

TAGS: ASTRONOMY, COMIC-CON, COMICS