Blogs | Dawn Journal | December 31, 2012

Dear Auld Dawn Synes

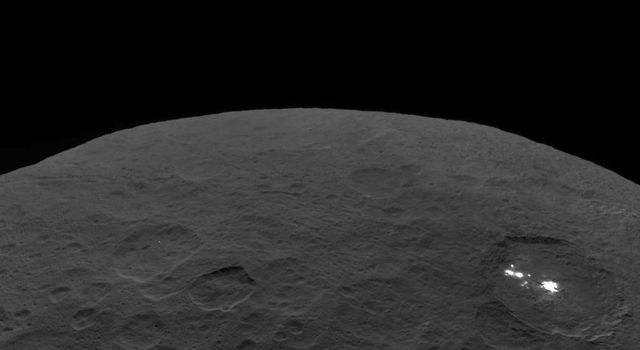

Dawn concludes 2012 almost 13,000 times farther from Vesta than it began the year. At that time, it was in its lowest orbit, circling the alien world at an average altitude of only 210 kilometers (130 miles), scrutinizing the mysterious protoplanet to tease out its secrets about the dawn of the solar system.

To conduct its richly detailed exploration, Dawn spent nearly 14 months in orbit around Vesta, bound by the behemoth's gravitational grip. In September they bid farewell, as the adventurer gently escaped from the long embrace and slipped back into orbit around the sun. The spaceship is on its own again in the main asteroid belt, its sights set on a 2015 rendezvous with dwarf planet Ceres. Its extensive ion thrusting is gradually enlarging its orbit and taking it ever farther from its erstwhile companion as their solar system paths diverge.

Meanwhile, on faraway Earth (and all the other locations throughout the cosmos where Dawnophiles reside), the trove of pictures and other precious measurements continue to be examined, analyzed, and admired by scientists and everyone else who yearns to glimpse distant celestial sights. And Earth itself, just as Vesta, Ceres, Dawn, and so many other members of the solar system family, continues to follow its own orbit around the sun.

Thanks to a coincidence of their independent trajectories, Earth and Dawn recently reached their smallest separation in well over a year, just as the tips of the hour hand and minute hand on a clock are relatively near every 65 minutes, 27 seconds. On Dec. 9, they were only 236 million kilometers (147 million miles) apart. Only? In human terms, this is not particularly close. Take a moment to let the immensity of their separation register. The International Space Station, for example, firmly in orbit around Earth, was 411 kilometers (255 miles) high that day, so our remote robotic explorer was 575 thousand times farther. If Earth were a soccer ball, the occupants of the orbiting outpost would have been a mere seven millimeters (less than a third of an inch) away. Our deep-space traveler would have been more than four kilometers (2.5 miles) from the ball. So although the planet and its extraterrestrial emissary were closer than usual, they were not in close proximity. Dawn remains extraordinarily far from all of its human friends and colleagues and the world they inhabit.

As the craft reshapes its solar orbit to match Ceres's, it will wind up farther from the sun than it was while at Vesta. (As a reminder, see the table here that illustrates Dawn's progress to each destination on its long interplanetary voyage.) We saw recently, however, that the route is complex, and the spacecraft is temporarily approaching the sun. Before the ship has had time to swing back out to a greater heliocentric range, Earth will have looped around again, and the two will briefly be even a little bit closer early in 2014. After that, however, they will never be so near each other again, as Dawn will climb higher and higher up the solar system hill, its quest for new and exciting knowledge of distant worlds taking it farther from the sun and hence from Earth.

Although our cosmic ambassador is much, much too remote to be discerned with our humble eyes, our far more powerful minds' eyes can locate it. As a convenient guide to begin, you can use the moon on Jan. 21. The details of the geometry will be somewhat dependent on your terrestrial position, which determines when the moon is above your horizon and how it aligns with the more distant cosmic landscape. Nevertheless, if you look at the moon that day, Dawn will appear to be nearby in the sky (although more than 670 times farther away). For observers in the continental United States, as the sun sets, the probe will be about five degrees to the east (left) of the moon, or about the width of three fingers held at arm's length. (Your correspondent has found that the measurement works best if you use not only your own fingers, but also your own arm.) As the evening progresses, they will draw closer and closer together. By the time the moon sinks below the western horizon at around 3:30 a.m. on Jan. 22, they will be separated by less than two degrees for observers on the east coast, and those on the west coast will find Dawn less than one degree away.

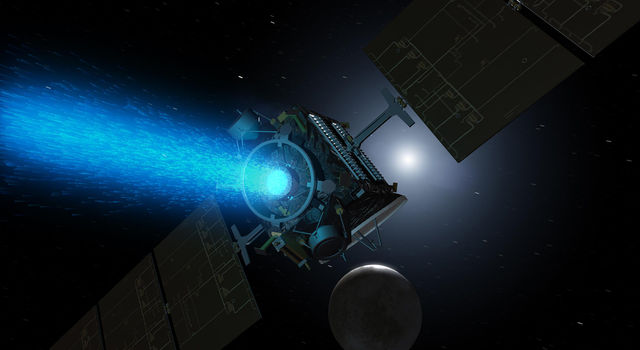

After using the moon to guide your eyes to the general location of the intrepid ship in the sky, let your mind take over. Allow it to transport you far, far into space, beyond all the human-made satellites around Earth, beyond the moon, beyond the orbit of Mars, and continue out farther than the sun (although in a different direction). Deep in the main asteroid belt, where no other spacecraft has ever taken up permanent residence and farther than all but a handful of probes have ever ventured, you can espy Dawn. Its long solar array wings, spanning nearly 20 meters (almost 65 feet) are pointing at the sun, capturing its light. A lovely beam of xenon ions glows blue-green as it propels the craft toward Ceres. Almost like a living creature, it is intensely active within; computers and myriad electronic circuits, heaters, and other components are working together to keep the ship flying true. Out there, in that direction, alone, far away from any firm surface or familiar ground, this Brobdingnagian celestial dragonfly flies gracefully, silently, and patiently toward its next planetary perch.

Dawn is 2.7 million kilometers (1.7 million miles) from Vesta and 57 million kilometers (38 million miles) from Ceres. It is also 1.65 AU (247 million kilometers or 153 million miles) from Earth, or 625 times as far as the moon and 1.68 times as far as the sun today. Radio signals, traveling at the universal limit of the speed of light, take 27 minutes to make the round trip.

Dr. Marc D. Rayman

6:30 p.m. PST December 31, 2012

TAGS:DAWN