Edu News | August 3, 2020

The Summer School for Space Mission Mavericks

When Jennifer Scully was a planetary geology grad student at UCLA in 2013, she happened upon an email that called for students to apply to something called the Planetary Science Summer School, or PSSS.

“I asked around and everybody only had positive things to say,” she says, “so I applied and I got in.”

She found herself in an immersive, 11-week program that teaches students all over the country how to formulate, design, and pitch a mission concept to a review board of NASA experts – essentially, how to bring a space mission to life from beginning to end.

“It was fabulous,” Scully says of her time in the program. “I come from a science background, and I had worked on an active planetary mission, but I didn’t have much experience with engineering. The summer school gave me my first exposure to mission-concept development and proposals. It was really illuminating.”

Seven years later, Scully is now a geologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, researching the asteroid Vesta and dwarf planet Ceres. She also plays a role in planning and designing missions to explore Jupiter's moon Europa. She’s still part of the PSSS program – but, now, as one of the mentors to this year’s cohort of 36 students looking at missions to Venus and Saturn's moon Enceladus.

The first 10 weeks of the program focus on formulation and always happen remotely via webinar. The final week usually culminates with an intensive in-person experience at JPL, during which participants write their mission proposal. Participants receive mentorship from scientists and engineers with the laboratory's Team X, a group that has been helping design and evaluate mission concepts since 1985. Even though the pandemic means their “culminating week” won’t take place physically at the laboratory this year, the students are still descending virtually on the JPL community between July 20 and Aug. 7 to learn the complex dance of what does and doesn’t work when it comes to dreaming up a NASA mission.

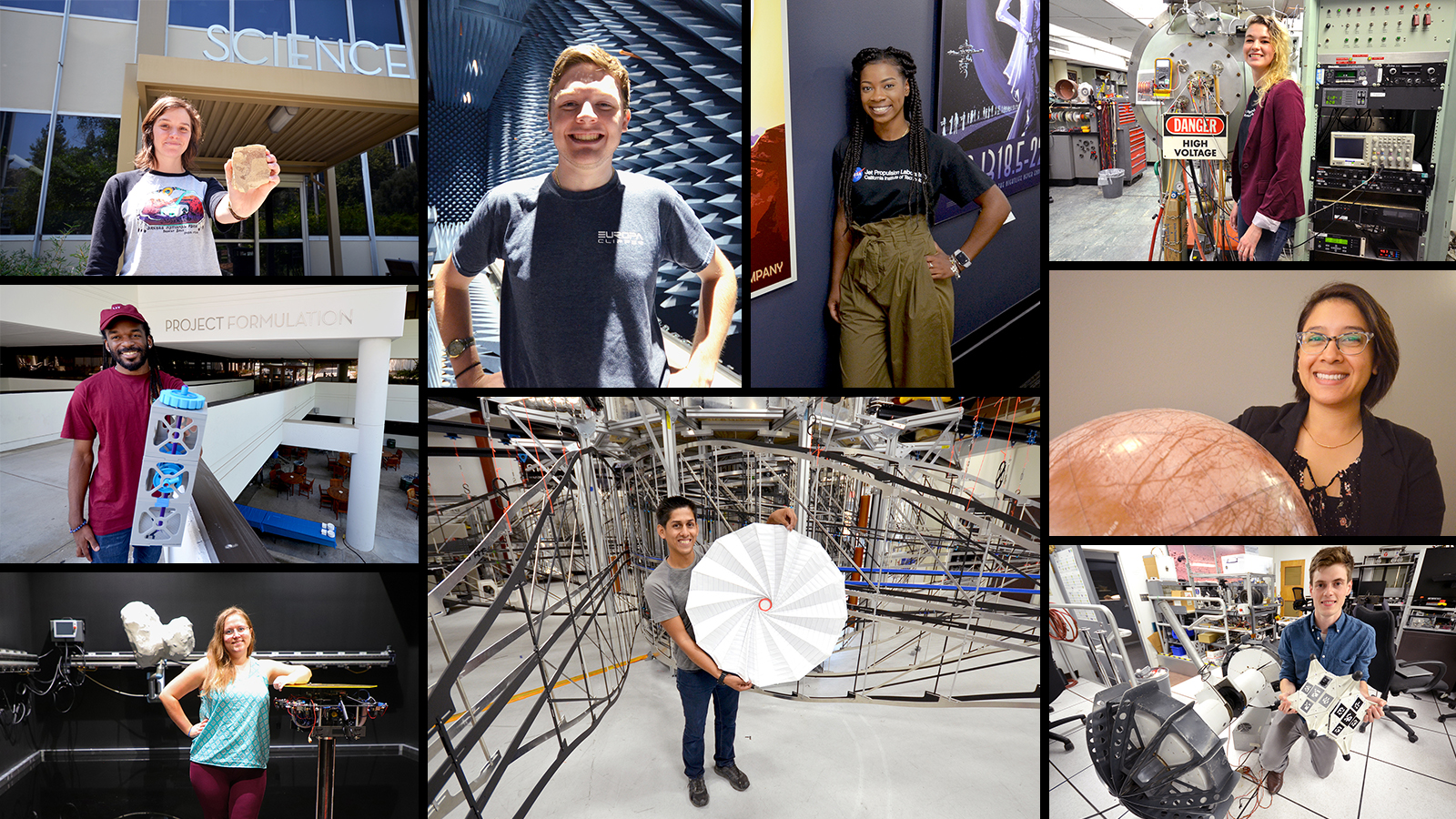

The first of two summer 2020 cohorts to arrive virtually at JPL for their culminating week in the PSSS program. While these one-week sessions are traditionally held in person, this year's group is meeting remotely. | + Expand image

“We do this for the broader planetary science mission community,” says PSSS manager Leslie Lowes, who’s been leading the program since 2010. “It’s about NASA training the next generation of scientists and engineers to do this type of work. Over 650 alumni use this model of mission design, and they’re in all kinds of leadership positions across NASA, including at JPL.”

Developed in 1989, the summer school started as a lecture series on how space missions could address the latest science discoveries and gradually shifted to a more hands-on format in 1999. Instead of hearing about the process, why not let students experience it?

“The first thing we do [when participants arrive at JPL] is help them evaluate potential architectures for their mission. Is it an orbiter or a lander? Is it a flyby?” says Alfred Nash, a mentor for the summer school and a lead engineer for Team X. “Does the science work? Do the engineering and cost work? The problem is not ‘can you make the thing,’ but ‘can you make the thing within the boundaries you have?’”

For Team X, it’s all about an integrated approach, which is one of the principal differences between how missions were developed in earlier days of exploration versus more recently. “Team X itself, its superpower is its ability to work in parallel and concurrently,” Nash says, stressing the importance of how the science should work in parallel with the engineering, the storytelling, the cost, and the project management.

A team of distinguished postdocs and graduate students learns what it's like to design a space mission in just five days as part of the 2014 session of NASA's Planetary Science Summer School at JPL. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | Watch on YouTube

“What is the big thing I’m trying to do? How do all the pieces work together? What is the foundational heart of this in terms of how we’re going to change humanity’s understanding? What are the pieces we need so that happens, and what does it take to do that?” are common questions Nash says Team X asks of all its mission proposals – including the concepts developed in PSSS.

One key lesson Nash tries to impart during the culminating week: “Win [the proposal] and don't regret it when you do,” he says. “The last thing you want to do is design a mission that no one can manage.”

If the students’ answers can pass the rigorous initial hurdles and meet the requirements for a NASA proposal, then they transition to design work. At that point, each student is paired with a mentor who has expertise in a range of engineering capabilities, from mission design to the science tools that will go on a spacecraft.

While this would normally mean working together at JPL, the program has gone virtual this year.

Team X had some practice setting up a virtual experience for the summer’s incoming students, as most JPL employees have been on mandatory telework since mid-March. Currently, the students are in a “waterfall of [web meeting] rooms,” as Nash describes it, where there’s one central meeting room and then individual “stations” in separate rooms, where students and mentors can interface while moving from room to room as needed. A typical day kicks off at 8 a.m. with a daily briefing. Then, students spend half the day with Team X and half the day on their own, preparing for the next day’s tasks. Their day ends at 5 p.m. with a briefing to review what was completed, what worked well, what didn’t, and what needs to change for the next day.

“Everyone knows science, if they’re a scientist, and engineering, if they’re an engineer,” says PSSS alumna Scully. “But now, they’re really trying to understand what mission development is about. This foundation will enable them to work with NASA much more effectively.”

The cohorts that arrive every year are formidable, and this summer’s group is no different: Among the students are 26 Ph.D. candidates and eight postdoctoral researchers.

For Elizabeth Spiers – a Ph.D. candidate studying the habitability of other planets at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and one of this summer’s students examining Enceladus’ ocean – PSSS has provided her with invaluable experience in real-time mission concept problem-solving.

“The project moves quickly and some of our decisions must be made equally as fast,” Spiers says. “Oftentimes, no person on our team knows the answers, and we need to figure out what we don’t know or understand about the problem so that we can ask the correct questions swiftly.”

In addition to critical thinking, the summer school also gives its students the chance to work with a diverse group of students and mentors.

NASA astronaut Jessica Watkins, an alumna of the program, attending her PSSS session in 2016 with mentor Bill Smythe. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | + Expand image

“It’s really exhilarating to see all of those disparate backgrounds and expertise come together into one cohesive project,” Spiers says. “I have learned so much about not only our project and the science and engineering related to it, but also about my teammates and their individual passions.”

Over the years, the program has taught students lessons they can carry with them throughout their careers. PSSS alumna Jessica Watkins went on to become a NASA astronaut and, at JPL, two summer school alumni-led development of science instruments on the Perseverance Mars rover – PIXL and SHERLOC. And this year, there’s a new star in the program, literally: The summer school is piloting a second experience called the Heliophysics Mission Design School to help strengthen hypothesis-driven science investigations when designing missions to the Sun.

Perhaps one lesson students will take away from PSSS is not only knowing what they want, but also recognizing the limits of space exploration.

“The most rewarding thing is seeing them make good decisions,” says Nash. “When they avoid trying to do something too expensive just because it’s cool. When they find a more fruitful way forward. What you want has nothing to do with it; it’s about what the world will let you do and how clever you are at navigating those boundaries.”

This feature is part of an ongoing series about the stories and experiences of JPL scientists, engineers, and technologists who paved a path to a career in STEM with the help of NASA's Planetary Science Summer School program. › Read more from the series

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of STEM Engagement’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

Career opportunities in STEM and beyond can be found online at jpl.jobs. Learn more about careers and life at JPL on LinkedIn and by following @nasajplcareers on Instagram.

TAGS: Higher Education, Internships, STEM, College Students, Virtual Internships, PSSS, Planetary Science Summer School, Ph.D. Programs, Science, Mission Design, PSSS Alumn

Meet JPL Interns | June 16, 2020

From Intern to Engineer, the Space Place is Where It's At

It only takes minutes into a conversation with Farah Alibay about her job at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory to realize there's nowhere else she'd rather be. An engineer working on the systems that NASA's next Mars rover will use to maneuver around a world millions of miles away, Alibay got her start at JPL as an intern. In the six years since being hired at the Laboratory, she's worked on several projects destined for Mars and even had a couple of her own interns. Returning intern Evan Kramer caught up with Alibay to learn more about her current role with the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover, how her internships helped pave her path to JPL and how she hopes interns see the same "beauty" in the work that she does.

What do you do at JPL?

I’m a systems engineer. I have two jobs on the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover mission right now. One is the systems engineer for the rover's attitude positioning and pointing. It's my job to make sure that once it's on the surface of Mars, the rover knows where it's pointed, and as it's moving, it can update its position and inform other systems of where it is. So we use things like a gyroscope and imagery to figure out where the rover is pointed and where it's gone as it's traveling.

My other job is helping out with testing the mast [sometimes called the "head"] on the rover. I help make sure that all of the commands and movements are well understood and well tested so that once the rover gets to Mars, we know that the procedures to deploy the mast and operate all of the instruments are going to work properly.

This is probably a tough question to answer, but what is an average day like for you?

Right now, I spend a lot of time testing – either developing procedures, executing procedures in the test bed or reviewing data from the procedures to make sure we're testing all of our capabilities. We start off from requirements of what we think we should be able to do, and then we write our procedures to test out those requirements. We test them out with software, and then we come to the test bed to execute them on hardware. Things usually go wrong, so we'll repeat the procedures a few times. Eventually, once we think we've had a successful run, we have a review.

Most of my testing is on the mobility side. However, it hasn't really started in earnest yet since we're waiting for the rover's "Earth twin" [the engineering model] to be built. Once that happens, later this summer, I will be spending a good chunk of my time in the Mars Yard [a simulated Mars environment at JPL], driving the rover around and actually using real data to figure out whether the software is behaving properly.

Watch the latest video updates and interviews with NASA scientists and engineers about the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover, launching to the Red Planet in summer 2020. | Watch on YouTube

What's the ultimate goal of your work at JPL?

All the work that I do right now is in support of the Perseverance rover mission. On the mobility team, we work on essential functions that are going to be used as the rover drives around on Mars.

One of the really neat things about Perseverance is that it can do autonomous driving. So the rover is able to drive up to 200 meters on its own, without us providing any directional information about the terrain. Working on this new ability has been the bulk of testing we're doing on the mobility team. But this new capability should speed up a lot of the driving that we do on Mars. Once we get smart in planning rover movements, we'll be able to plan a day's worth of activity and then tell the rover, "Just keep going until you're done."

You came to JPL as an intern. What was that experience like and how did it shape what you're doing now?

I spent two summers as an intern at JPL during my Ph.D. The first one was in 2012, which was the summer that the Curiosity Mars rover landed. That was a pretty incredible experience. As someone who had only spent one summer at NASA before, seeing the excitement around landing a spacecraft on Mars, well, I think it's hard not to fall in love with JPL when you see that happen. During that summer, I worked on the early days of the A-Team [JPL's mission-concept study team], where I was helping out with some of the mission studies that were going on.

My second summer, I worked in the Mars Program Office, looking at a mission concept to return samples from Mars. I was helping define requirements and look at some of the trade studies. We were specifically looking at designs for orbiters that could bring back samples from Mars. A lot of that fed into my graduate research. It's pretty cool to be able to say that I applied my research and research tools to real problems to help JPL's Mars sample return studies.

What brought you to JPL for your internship? Was working at JPL always a dream for you?

Yeah, working at NASA was always a dream, but going into my Ph.D., I became more and more interested in robotics and planetary exploration. I have a Ph.D. in aerospace engineering, but I also have a minor in planetary science. There are very few places on Earth that really put those two together besides JPL, and it's the only place that has successfully landed a spacecraft on Mars. So, given my passions and my interests, JPL emerged at the top of my list very, very quickly. Once I spent time here, I realized that I fit in. My work goals and my aspirations fit into what people were already doing here.

What moments or memories from your internships stand out the most?

The Curiosity landing was definitely one of the highlights of my first internship.

Another one of the highlights is that JPL takes the work that interns do really seriously. I was initially surprised by that, and I think that's true of every intern I've met. Interns do real work that contributes to missions or research. I remember, for example, presenting some of my work to my mentor, who was super-excited about some of the results I was getting. For me, that was quite humbling, because I saw my research actually helping a real mission. I think I'll always remember that.

How do you think your internship shaped your career path and led to what you're doing now?

My internships definitely opened a lot of doors for me. In particular, during my second internship, I also participated in the Planetary Science Summer School at JPL. Throughout the summer, we met with experts in planetary science to develop a mission concept, and then we came together as a team to design the spacecraft in one week! It was an intense week but also an extremely satisfying one. The highlight was being able to present our work to some of the leading engineers and scientists at JPL. We got grilled, and they found a whole lot of holes in our design, but I learned so much from it. How often do you get to have your work reviewed by experts in the field?

Through these experiences, I made a lot of connections and found mentors who I could reach out to. Since I knew JPL is where I wanted to be, I took it upon myself to knock on every single door and make my case as to why JPL should hire me. I actually never interviewed, because by then, they decided that I had done my own interviews!

My internships and the summer school also gave me an idea of what I wanted to do and what I didn't want to do. So I was a step ahead of other applicants. I always tell interns who come to JPL that if they're not particularly liking their work in the first few weeks, they should take the opportunity to go out and explore what else JPL has to offer. I believe that there's a place for everyone here.

Have you had your own interns before?

I had interns my first two summers working at JPL. Two of my interns are now also full-time employees, and I always remind them that they were my interns when I see them! I also have an intern this summer who I'm extremely excited to work with, as she'll be helping us prepare some of the tools we'll need for operating the Perseverance rover on Mars.

What is your mentorship style with interns?

My goal for interns is mostly for them to learn something new and discover JPL, so I usually let my interns drive in terms of what they want to achieve. Normally, I sit down with them at the start of summer and define a task, because we want them to be doing relevant work. But I encouraged them to take time off from what they're doing and explore JPL, attend events that we have organized for interns and decide whether this is a place for them or not.

It's kind of a dual mentorship. I mentor them in terms of doing their work, but also mentor them in terms of helping them evolve as students and as early career engineers.

What do you hope they take away from their experience?

I hope they take advantage of this unique place and that they fall in love with it the way I did. Mostly, though, I'm hoping they discover whether this is a place for them or not. Whatever it is, I want them to be able to find their passion.

What would be your advice for those looking to intern or work at JPL one day?

I think the way into JPL, or whatever career that you're going to end up in, is to be 100% into what you're doing. If you're in school, studying aerospace engineering or mechanical engineering, do hands-on projects. The way I found opportunities was through the Planetary Science Summer School and the Caltech Space Challenge, which were workshops. I also did something called RASC-AL, which is a different workshop from the National Institute of Aerospace. Do all of those extracurricular things that apply your skills and develop them.

If you have the opportunity to attend talks, or if your advisor gives you extra work that requires you to reach out to potential mentors, take the time to do it.

My other piece of advice is to knock on doors and talk to people who do something in your field that you're interested in. Don't be shy, and don't wait for opportunities to come to you. Especially if you're already at JPL, or if you have mentors that are. Leverage that network.

Last question: If you could play any role in NASA's mission to send humans back to the Moon and eventually on to Mars, what would it be?

I chose to come to JPL because I like working on robotic missions. However, a lot of these robotic missions are precursors to crewed lunar and Mars missions. So I see our role here as building up our understanding of Mars and the Moon [to pave the way for future human missions].

I've worked on different Mars missions, and every one has found unexpected results. We're learning new things about the environment, the soil and the atmosphere with every mission. So I already feel like my work is contributing to that. And especially with the Perseverance rover mission, one of its main intentions is to pave the way for eventually sending humans to Mars.

This story is part of an ongoing series about the career paths and experiences of JPL scientists, engineers, and technologists who got their start as interns at the Southern California laboratory. › Read more from the series

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of STEM Engagement’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

Career opportunities in STEM and beyond can be found online at jpl.jobs. Learn more about careers and life at JPL on LinkedIn and by following @nasajplcareers on Instagram.

TAGS: Mars, Mars Rover, Perseverance, Mars 2020, Mars 2020 Interns, PSSS, Planetary Science Summer School, Internships, Workshops, Career Advice, Mentors, Where Are They Now, Women at NASA

Career Guidance | June 16, 2020

Scientist on a Mission

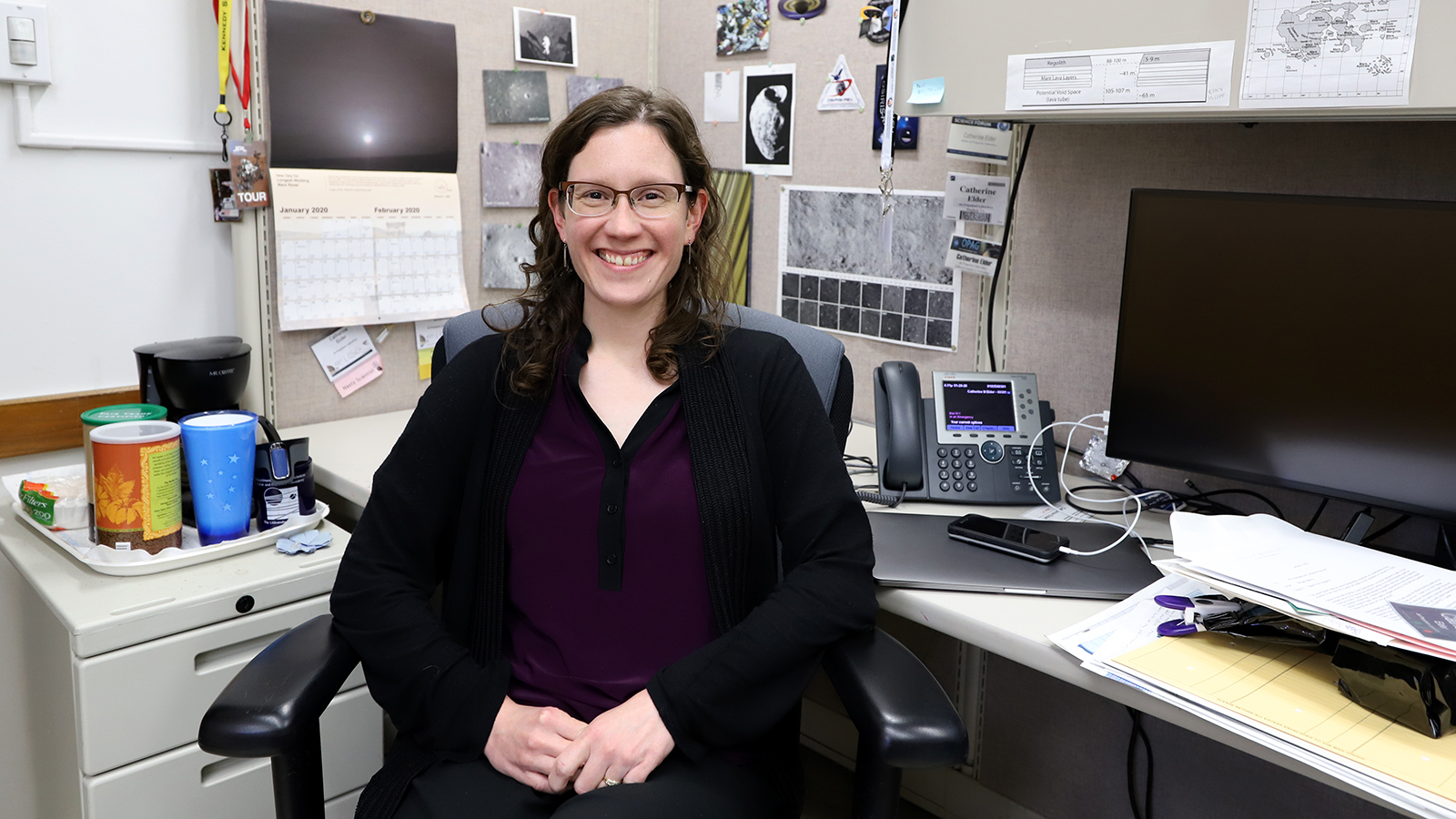

Catherine Elder's office is a small, cavernous space decorated with pictures of the Moon and other distant worlds she studies as a research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Elder has been interested in space science since she was young, but she didn't always imagine she'd be working at one of the few places that builds robotic spacecraft designed to venture to mysterious worlds. A doctorate in planetary science – the study of the evolution of planets and other bodies in space – first brought her to JPL five years ago for research into the geologic history of the Moon. She planned to eventually become a professor, but a sort of gravitational pull has kept her at the laboratory, where in addition to lunar science, she's now involved in projects studying asteroids, Jupiter's moon Europa and future missions. We met up with her earlier this year to talk about her journey, how a program at JPL helped set her career in motion and how she's paying it forward as a mentor to interns.

What do you do at JPL?

A lot of what I do is research science. So that involves interpreting data from spacecraft and doing some modeling to understand the physical properties of places like the Moon, asteroids and Jupiter's moon Europa.

I am also working on mission formulation. So in that case, my role is to work with the engineers to make sure that the missions we're designing will actually be able to obtain the data that we need in order to answer the science questions that we have.

Tell us about some of the projects you're working on.

A lot of my work right now is looking at the Moon. I'm on the team for the Diviner instrument on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. That instrument observes the Moon in infrared, which we can use to understand the geologic history, such as how rocks break down over time. We can also look at specific features, like volcanoes, and understand their material properties. I do similar work on the OSIRIS-REx mission [which aims to return a sample from the asteroid Bennu].

I'm on the Europa Clipper team right now. I'm the investigation scientist for the cameras on the mission [which is designed to make flybys of Jupiter's moon Europa]. So I serve as a liaison between the camera team and other parts of the project.

I'm also working on a project modeling the convection in the rocky portion of Europa, underneath the liquid-water layer. Our goal is to understand how likely it is that there are volcanoes on the seafloor of Europa. A lot of scientists in their previous work have suggested that life could originate in these volcanoes. So we're going back and looking at how likely it is that they exist.

Sounds like fascinating work and like you're keeping busy! What is your average day like?

When I'm analyzing the data and doing modeling, I'm usually at my computer. I do a lot of computer coding and programming. We do a lot of modeling to help interpret the data that we get. For example, if we think we know the physical properties of a surface, how are those going to affect how the surface heats up or cools down over the course of a day? I compare what we find to the observations [from spacecraft] and circle back and forth until we have a better idea of what those surface materials are like.

Then, for the mission work, it's a lot more meetings. I'm in meetings with the engineers and with other scientists, talking about mission requirements, observation plans and things like that.

Tell us a bit about your background and what brought you to JPL.

I have wanted to be an astronomer since I was nine years old. So I was an astronomy major at Cornell University in New York. I didn't really realize planetary science existed, but luckily Cornell is one of the few universities where planetary science is in the astronomy department. A lot of times it's in the geology department. I started to learn more about planetary science by taking classes and realized that was what I was really interested in. So I went to the University of Arizona for grad school and got a Ph.D. in planetary science.

I thought I eventually wanted to be a professor somewhere. A postdoc position is kind of a stepping stone between grad school and faculty positions or other more permanent positions. So I was looking for a postdoc, and I found one at JPL. It was pretty different from what my thesis work had been on, but it sounded really interesting. I didn't think I was going to stay at JPL, but I ended up really liking it, and I got hired as a research scientist.

You also took part in the Planetary Science Summer School at JPL, working on a simulated mission design project. What made you want to apply for that program and what was the experience like?

I've always been interested in missions. I began PSSS when I was a postdoc at JPL, so I was already working with mission data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. But by the time I joined the team, LRO had been orbiting the Moon for more than five years, so it was a well oiled machine.

I was interested in thinking about future missions and how you design one. So PSSS was a really great experience. They gave us a couple targets that we could pick between, and we picked Uranus. We had to come up with all the science objectives we would want to have if we visited Uranus [with a robotic spacecraft]. We had a mix of scientists and engineers, but none of us had studied Uranus, so we had to do a lot of background reading and figure out the big outstanding questions about the planet and its moons. We came up with a ton of them. When we did our first session with Team X, which is JPL's mission formulation team, we realized that we had way too many objectives, and we were never going to be able to achieve all of them in the budget that we had. It was a big wake up call. We had to narrow the scope of what we wanted to do a lot.

Then we had two more sessions with Team X, and we eventually came up with a concept where we were within the budget and we had a couple of instruments that could answer some science questions. Then we presented the mission idea to scientists and engineers at JPL and NASA headquarters who volunteered as judges.

Participants in the Planetary Science Summer School are assigned various roles that are found on real mission design teams. What role did you play?

I had the role of principal investigator [which is the lead scientist for the mission].

How did that experience shape what you're doing today?

Actually, quite a bit. Learning how you develop a science objective and thinking through it, you start with goals like, "I want to understand the formation and evolution of the solar system." That's a huge question. You're never going to answer it in one mission. So the next step is to come up with a testable hypothesis, which for Uranus could be something like, "Is Uranus' current orbit where it originally formed?" And then you have to come up with measurement objectives that can address that hypothesis. Then you have to think about which instruments you need to make those measurements. So learning about that whole process has helped a lot, and it's similar to what I'm doing on the Europa mission now.

Elder sits in her office in the "science building" at JPL surrounded by images of the places she's working to learn more about. More than just pretty pictures, the images from spacecraft are also one of the key ways she and her interns study moons and planets from afar. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech | + Expand image

I also got really interested in the Uranus system, specifically the moons, because they show a lot of signs of recent geologic activity. They might be just as interesting as the moons of Saturn and Jupiter. But Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft that has visited them. At that time, only half of the moons were illuminated, so we've only seen half of these moons. I really want a mission to go back and look at the other half.

Recently, me and a few friends at JPL – two who also did PSSS and one who did a very similar mission formulation program in Europe – got really interested in the Uranus system. So now, in our free time, we're developing a mission concept to study the Uranus system and trying to convince the planetary science community that it’s worth going back to it.

Are there any other moments or memories from PSSS that stand out?

Actually, one I was thinking about recently is that I was in the same session as Jessica Watkins, who recently became a NASA astronaut. I remember I was super stressed out because we had to give this presentation, and me and the project manager, who is a good friend of mine, were disagreeing on some things. But I talked to Jess, and she was just so calm and understanding. So when she got selected as an astronaut, I was like, "That makes sense," [laughs].

But the other thing that stands out is we worked so hard that week. We were at JPL during the day. And in the evening, we would meet again and work another four hours. Now that I'm working on mission development for actual missions, I realize there's so much more that actually goes into a mission, but PSSS gives you a sense of how planetary missions are such a big endeavor. You really need to work as a team.

You've also served as a mentor, bringing interns to JPL. Tell us a bit about that experience and what made you interested in being a mentor?

I've worked with five students at this point, all undergrads. I've always been interested in being a mentor. I was a teaching assistant for a lot of grad school, and I really enjoyed that. I like working one-on-one with students. I find it really rewarding, too, because it helps you remember how cool the stuff you're doing really is. The interns are learning it for the first time, so being able to explain exciting things about the solar system to them for the first time is pretty fun.

What do you usually look for when choosing an intern?

Enthusiasm is a big one. At the undergrad level, most people haven't specialized that much yet; they have pretty similar backgrounds. So I think enthusiasm is usually what I use to identify candidates. Is this what they really want to be doing? Are they actually interested in the science of planets?

What kinds of things do you typically have interns do?

It varies. It can sometimes be repetitive, like looking at a lot of images and looking for differences between them. One of the projects I have a lot of students working on right now is looking at images of craters on the Moon. There's this class of craters on the Moon that we know are really young. By comparing the material excavated by them, we can actually learn about the Moon's subsurface. So I have students going through and looking at how rocky those craters are. We're basically trying to map the subsurface rocks on the Moon. So that can get a little repetitive, but I find that some students actually end up really liking it, and find it kind of relaxing [laughs].

For students who intern with me longer, I try to tailor it to their interests and their skill set. One student, Jose Martinez-Camacho, was really good at numerical modeling and understanding thermodynamics, so he was developing his own models to understand where ice might be stable near the lunar poles.

What's your mentorship philosophy? What do you want students to walk away with?

I think mentors are usually biased in that they want their students to turn out like them. So I'm always excited when my students decide they want to go to grad school, but grad school is not the path for everyone.

One of the important things to learn from doing research is how to solve a problem on your own. A lot of times coursework can be pretty formulaic, and you're learning how to solve one type of problem so that you can solve a similar problem. But with research, unexpected things come up, and you have to learn how to troubleshoot on your own. I think you learn a little bit about that as an intern.

What's the value of JPL internships and fellowships from your perspective?

We're lucky at JPL that we're working on really exciting things. I think we should share that with as many people as possible, and internships are a good way to do that.

Then, for me personally, participating in PSSS solidified that I was on the right path. I knew I wanted to continue to be involved in mission formulation, and that was a big part of why I decided to stay at JPL, to be really deeply involved in the formulation of space missions. There's only a handful of places in the world where you can do that.

This feature is part of an ongoing series about the stories and experiences of JPL scientists, engineers, and technologists who paved a path to a career in STEM with the help of NASA's Planetary Science Summer School program. › Read more from the series

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of STEM Engagement’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

Career opportunities in STEM and beyond can be found online at jpl.jobs. Learn more about careers and life at JPL on LinkedIn and by following @nasajplcareers on Instagram.

TAGS: Higher Education, Internships, STEM, Mentors, Science, Moon, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, PSSS, Planetary Science Summer School, Careers, Research, Science, Women at NASA

Meet JPL Interns | January 10, 2020

From Interns to Astronauts: Former JPL Interns Join NASA Astronaut Class

Former JPL Interns Graduate From NASA Astronaut Class

Update: Jan. 10, 2020 – In a ceremony at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Jessica Watkins, Loral O’Hara and Warren Hoburg graduated from basic training along with fellow astronaut candidates. As members of NASA’s Astronaut Corps, they are now eligible for spaceflight, including assignments to the International Space Station, Artemis missions to the Moon, and ultimately, missions to Mars.

Originally published June 15, 2017:

Three former interns of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory are joining the agency’s newest class of astronaut candidates. Jessica Watkins, Loral O’Hara and Warren "Woody" Hoburg were among 12 selected for the coveted spots announced by the agency on Wednesday.

Adrian Ponce, manager of JPL’s Higher Education Programs, congratulated the new astronaut candidates and emphasized the value of the laboratory’s internship programs, which bring in about 1,000 students each year to work with researchers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.

"JPL is recognized in the world as a place of innovation, and interns have the opportunity to operate alongside researchers, contribute to NASA missions and science, develop technology and participate in making new discoveries," said Ponce, adding that the internship experience serves as a pathway to careers at JPL, aerospace companies, tech giants – and now the NASA astronaut corps.

While there’s no single formula for becoming an astronaut, experience at a NASA center certainly helps. In fact, many NASA scientists and engineers already working in their dream jobs landing rovers on Mars or discovering planets beyond our solar system, still aspire to become astronauts.

Watkins, who as a graduate student participated in several internships at JPL that had her analyzing near-Earth asteroids and planning ground operations for the Mars Curiosity rover, says that becoming an astronaut was a childhood dream that just “never went away.” In a video interview during her internship with the Maximizing Student Potential, or MSP, program in 2014, she talked about how she saw her experiences at JPL as a key step to fulfilling her goal.

“When you walk away from having an internship at JPL, I think you just have a broader perspective on what’s possible and what’s feasible,” said Watkins, who in 2016 participated in another program from JPL’s Education Office, an intensive, one-week mission formulation program called Planetary Science Summer Seminar. “I think you set a new standard for yourself just by being around people who have set the standard really high for themselves. You learn to appreciate the possibilities and the things that you really are capable of achieving.”

This story is part of an ongoing series about the career paths and experiences of JPL scientists, engineers, and technologists who got their start as interns at the Southern California laboratory. › Read more from the series

The laboratory’s STEM internship and fellowship programs are managed by the JPL Education Office. Extending the NASA Office of STEM Engagement’s reach, JPL Education seeks to create the next generation of scientists, engineers, technologists and space explorers by supporting educators and bringing the excitement of NASA missions and science to learners of all ages.

Career opportunities in STEM and beyond can be found online at jpl.jobs. Learn more about careers and life at JPL on LinkedIn and by following @nasajplcareers on Instagram.

TAGS: Women in STEM, Astronaut, Internship, Career Advice, Jessica Watkins, Loral O'Hara, PSSS, Planetary Science Summer School, NASA Science Mission Design Schools, SMDS, Where Are They Now, Women at NASA

Meet JPL Interns | December 13, 2011

Mission Makers: Planetary Science Summer School

Each summer, NASA's Planetary Science Summer School program brings a team of distinguished postdocs and graduate students to the laboratory to learn what its

like to design a space mission. Watch how the talented team puts together a mission concept in just five days.