Teachable Moments | September 12, 2017

A Moment You Won't Want to Miss: Cassini's Mission Finale at Saturn

Update – Sept. 11, 2017: This feature (originally published on April 25, 2017) has been updated to reflect Cassini's current mission status, as well as new lessons and activities.

- Visit the Cassini website's Grand Finale Toolkit for a timeline, resources and more information about the final phase of the mission.

- Follow along with NASA via live stream during the Grand Finale on September 15 and in the days leading up to the event. Programming begins on September 13 at 10 a.m. PDT.

- Get the latest news and updates for the Cassini mission on the JPL News website.

- Explore these standards-aligned lessons and out-of-school activities to bring the wonder of NASA's Cassini mission and science at Saturn to students.

In the News

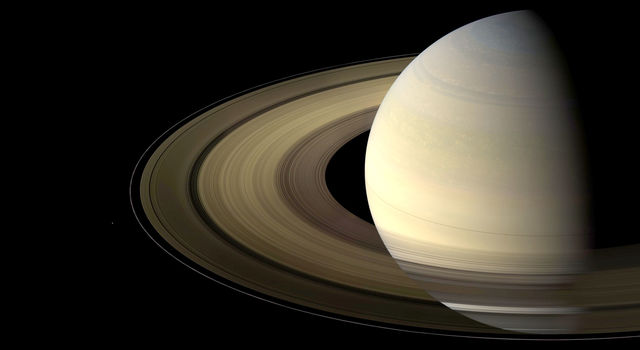

After almost 20 years in space, NASA's Cassini spacecraft has begun the final chapter of its remarkable story of exploration. This last phase of the mission has delivered unprecedented views of Saturn and taken Cassini where no spacecraft has been before – all the way between the planet and its rings. On Friday, Sept. 15 Cassini will perform its Grand Finale: a farewell dive into Saturn’s atmosphere to protect the environments of Saturn’s moons, including the potentially habitable Enceladus.

Lessons All About Saturn

Explore our collection of standards-aligned lessons about NASA's Cassini mission.

How It Works

On April 22, Cassini flew within 608 miles (979 km) of Saturn’s giant moon Titan, using the moon’s gravity to place the spacecraft on its path for the ring-gap orbits. Without this gravity assist from Titan, the daring, science-rich mission ending would not be possible.

Cassini is almost out of the propellant that fuels its main engine, which is used to make large course adjustments. A course adjustment requires energy. Because the spacecraft does not have enough rocket fuel on board, Cassini engineers have used an external energy source to set the spacecraft on its new trajectory: the gravity of Saturn’s moon Titan. (The engineers have often used Titan to make major shifts in Cassini’s flight plan.)

Titan is a massive moon and thus has a significant amount of gravity. As Cassini comes near Titan, the spacecraft is affected by this gravity – and can use it to its advantage. Often referred to as a “slingshot maneuver,” a gravity assist is a powerful tool, which uses the gravity of another body to speed up, slow down or otherwise alter the orbital path of a spacecraft.

In this installment of the "Crazy Engineering" video series from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, host Mike Meacham talks to a Cassini engineer about astrodynamics and how it was used to design the Saturn mission's Grand Finale.

When Cassini passed close by Titan on April 22, the moon’s gravity pulled strongly on the spacecraft. The flyby gave Cassini a change in velocity of about 1,800 mph (800 meters per second) that sent the spacecraft into its first of the ring-gap orbits on April 23. On April 26, Cassini made its first of 22 daring plunges between the planet and its mighty rings.

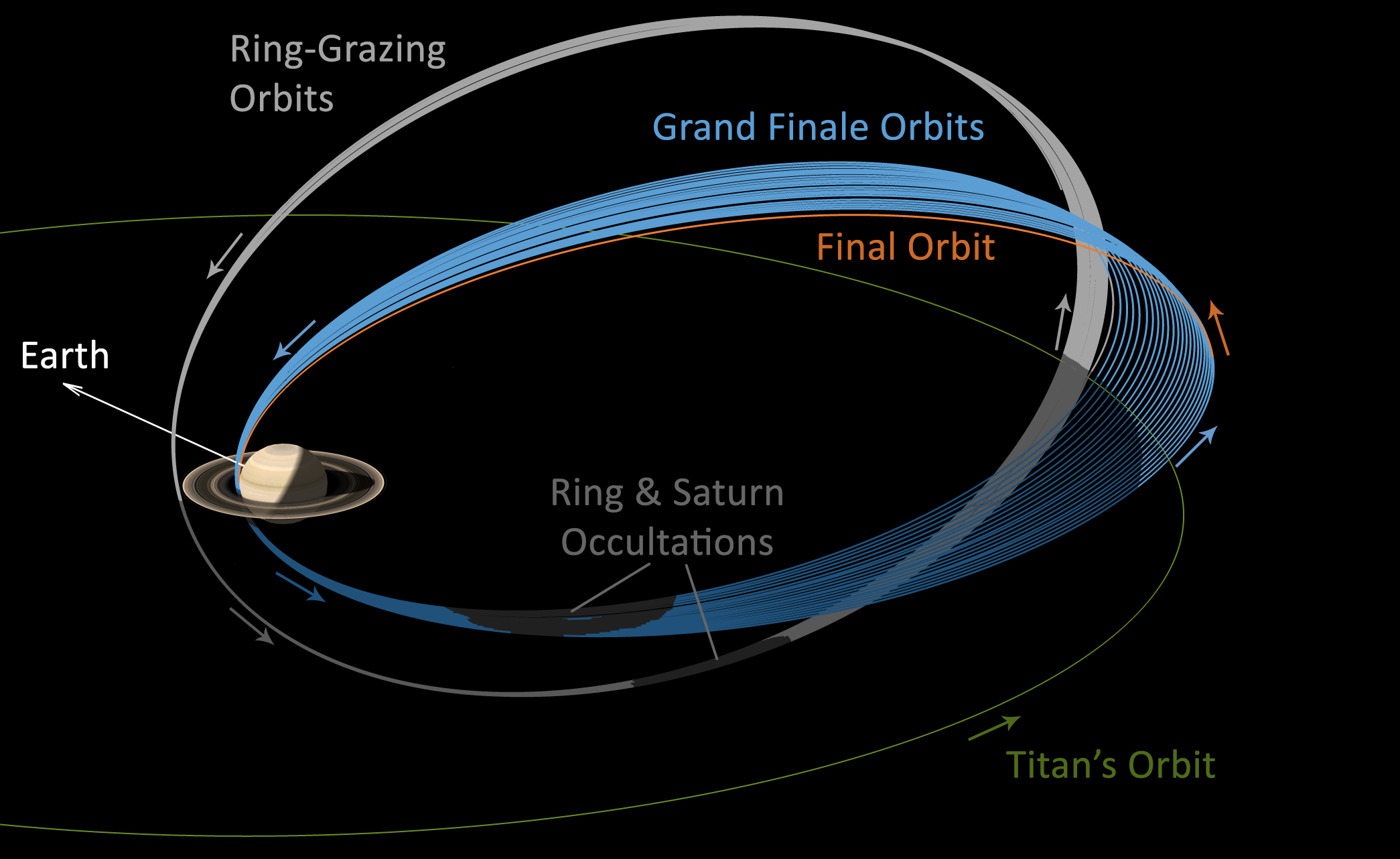

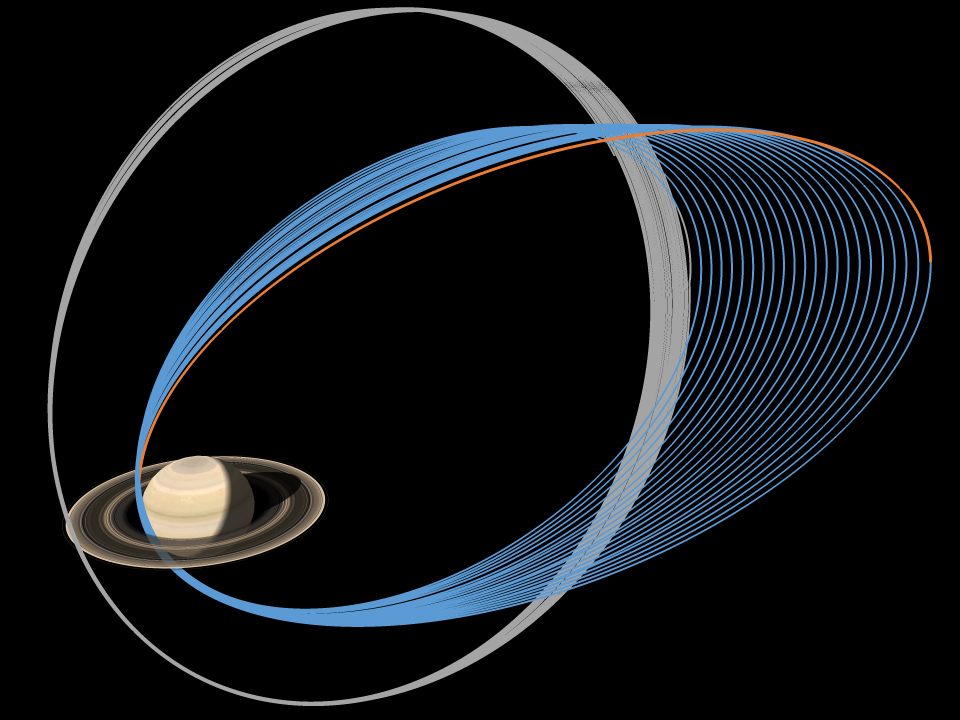

This graphic illustrates Cassini's trajectory, or flight path, during the final two phases of its mission. The 20 Ring-Grazing Orbits that Cassini made between November and April 2017 are shown in gray; the 22 Grand Finale Orbits are shown in blue. The final partial orbit is colored orange. + Enlarge image

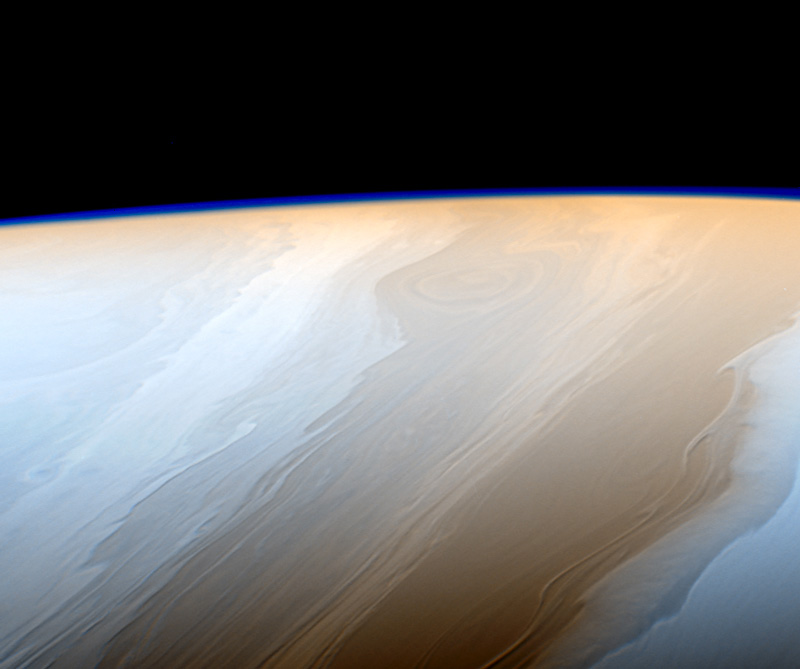

Clouds on Saturn take on the appearance of strokes from a cosmic brush thanks to the wavy way that fluids interact in Saturn's atmosphere. This images used in this false-color view were taken with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 18, 2017. Image credit: NASA-JPL/Caltech/SSI | › Full image and caption

This animated image of Saturn's moon Enceladus is a composite of six images taken by the Cassini spacecraft on Aug. 1, 2017. Image credit: NASA-JPL/Caltech/SSI | › Full image and caption

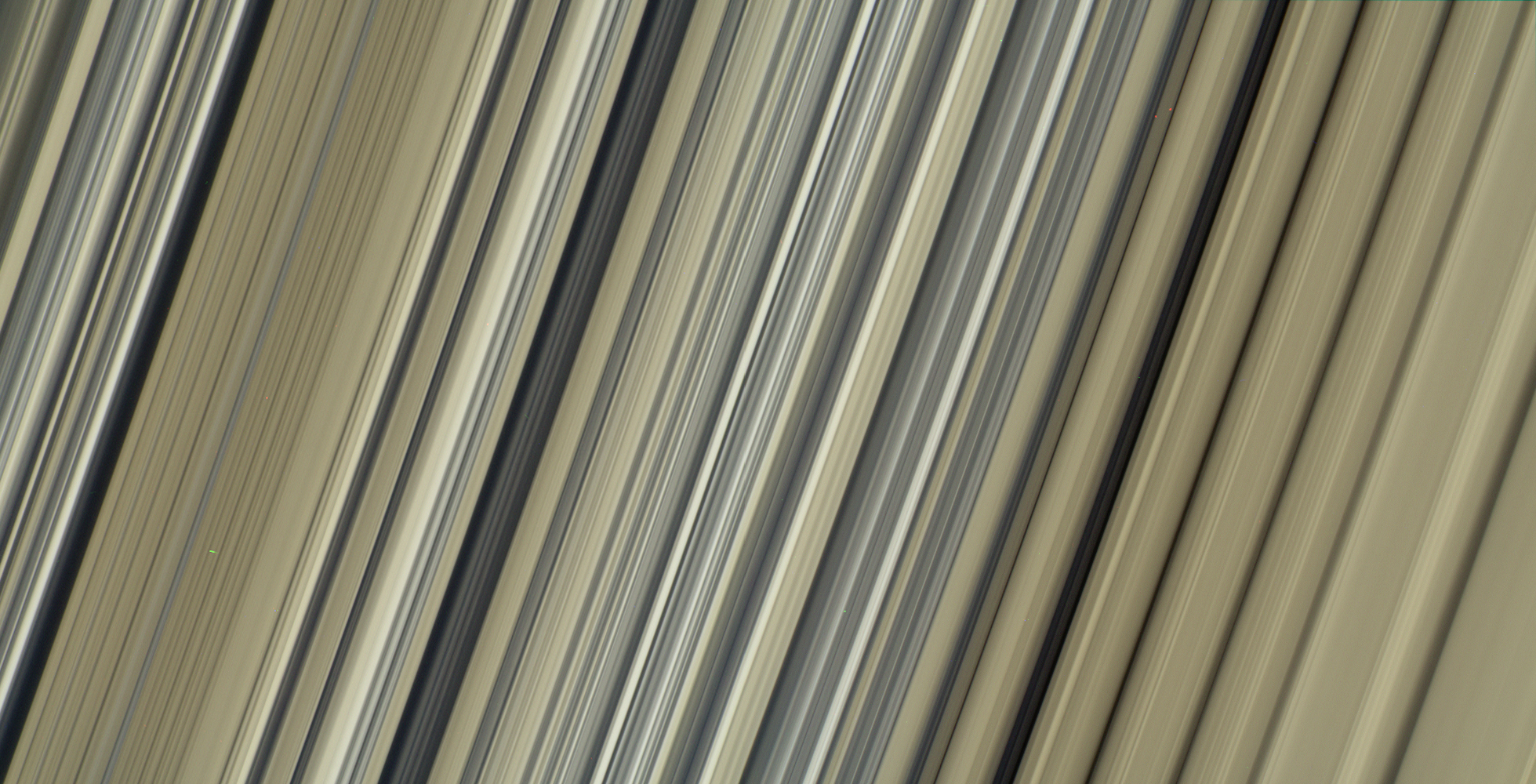

These are the highest-resolution color images of any part of Saturn's rings, to date, showing a portion of the inner-central part of the planet's B Ring. The view is a mosaic of two images that show a region that lies between 61,300 and 65,600 miles (98,600 and 105,500 kilometers) from Saturn's center. Image credit: NASA-JPL/Caltech/SSI | › Full image and caption

As Kepler’s third law indicates, Cassini traveled faster than ever before during these final smaller orbits. Cassini's orbit continued to cross the orbit of Titan during these ring-gap orbits. And every couple of orbits, Titan passed near enough to give the spacecraft a nudge. One last nudge occured on September 11, placing the spacecraft on its final, half-orbit, impact trajectory toward Saturn.

Because a few hardy microbes from Earth might have survived onboard Cassini all these years, NASA has chosen to safely dispose of the spacecraft in the atmosphere of Saturn to avoid the possibility of Cassini someday colliding with and contaminating moons such as Enceladus and Titan that may hold the potential for life. Cassini will continue to send back science measurements as long as it is able to transmit during its final dive into Saturn.

Why It’s Important

Flying closer than ever before to Saturn and its rings has provided an unprecedented opportunity for science. During these orbits, Cassini’s cameras have captured ultra-close images of the planet’s clouds and the mysterious north polar hexagon, helping us to learn more about Saturn’s atmosphere and turbulent storms.

The cameras have been taking high-resolution images of the rings, and to improve our knowledge of how much material is in the rings, Cassini has also been conducting gravitational measurements. Cassini's particle detectors have sampled icy ring particles being funneled into the atmosphere by Saturn's magnetic field. Data and images from these observations are helping bring us closer to understanding the origins of Saturn’s massive ring system.

Cassini has also been making detailed maps of Saturn's gravity and magnetic fields to reveal how the planet is structured internally, which could help solve the great mystery of just how fast Saturn is rotating.

On its first pass through the unexplored 1,500-mile-wide (2,400-kilometer) space between the rings and the planet, Cassini was oriented so that its high-gain antenna faced forward, shielding the delicate scientific instruments from potential impacts by ring particles. After this first ring crossing informed scientists about the low number of particles at that particular point in the gap, the spacecraft was oriented differently for the next four orbits, providing the science instruments unique observing angles. For ring crossings 6, 7 and 12, the spacecraft was again oriented so that its high-gain antenna faced forward.

Fittingly, Cassini's final moments will be spent doing what it does best, returning data on never-before-observed regions of the Saturnian system. On September 15, just hours before Cassini enters Saturn's atmosphere for its Grand Finale dive, it will collect and transmit its final images back to Earth. During its fateful dive, Cassini will be sending home new data in real time informing us about Saturn’s atmospheric composition. It's our last chance to gather intimate data about Saturn and its rings – until another spacecraft journeys to this distant planet.

Explore the many discoveries made by Cassini and the story of the mission on the Cassini website.

Teach It

Use these standards-aligned lessons to get your students excited about the science we have learned and have yet to learn about the Saturnian system.

- NEW! Activity Collection: Jewel of the Solar System – Explore Saturn and the Cassini mission with this eight-part series of activities targeting after-school settings.

- Jewel of the Solar System Activity Guide

- What Do I See When I Picture Saturn?

- Where Are We in the Solar System?

- Discovering Saturn: The Real "Lord of the Rings"

- Saturn's Fascinating Features

- My Spacecraft to Saturn

- All About Titan and Huygens Probe

- Drop Zone! Design and Test a Probe

- Celebrating Saturn and Cassini

- Lesson: Flying By Saturn's Moon Enceladus – Teach students about Saturn's scientifically intriguing moon Enceladus and investigate its fascinating features, including its ocean and plumes, using math.

- Video Lesson: Bouncing Radio Waves Off Titan's Lakes – Learn about one way we study Titan in this educational video.

- Problem Set: Pi in the Sky – Have older students use mathematics to calculate Cassini's fuel reserves.

- Problem Set: Pi in the Sky 4 – Students can also calculate the date of the spacecraft's Grand Finale dive into Saturn.

- Download a poster of Saturn and the Cassini mission timeline.

- Download these Cassini retro posters: Whoosh | Swan Song | The Classic

Explore More

- Cassini Lessons for Educators

- Cassini Activities for Students

- Cassini Mission Website

- Cassini Grand Finale Toolkit

- Cassini Mission Overview

- Interactive Cassini Mission Timeline

- Video: NASA VR: Cassini's Grand Finale (360 Video)

- Slideshow for Students (includes a free poster!): 8 Real World Space Facts About Saturn's Moon Enceladus

- Slideshow for Students (includes a free poster!): Ocean Worlds

- Explore the Cassini Spacecraft in 3-D

- The Saturn System Through the Eyes of Cassini (e-book)

TAGS: Saturn, Titan, Cassini, Grand Finale, Teachable Moments, Kepler's Laws, K-12, Lessons, Ocean Worlds

Teachable Moments | November 22, 2016

Spacecraft's 'Ring-Grazing' Maneuver to Deliver New Science from Saturn

Update – Feb. 24, 2017: The deadline for the Cassini Scientist for a Day Essay Contest has passed. The winners will be announced in May 2017.

In the News

Next week, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will go where no spacecraft has gone before when it flies just past the edge of Saturn’s main rings. The maneuver is a first for the spacecraft, which has spent more than 12 years orbiting the ringed giant planet. And it’s part of a lead-up to a series of increasingly awesome feats that make up the mission’s “Grand Finale” ending with Cassini’s plunge into Saturn on Sept. 15, 2017.

How They’ll Do It

Cassini's ring-grazing orbits, which will take place from late Novemeber 2016 through April 2017, are shown here in tan. The blue lines represent the path that Cassini took in the time leading up to the new orbits during its extended solstice mission. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute | › Larger image

To prepare for the so-called “ring-grazing orbits,” which will bring the spacecraft within 56,000 miles (90,000 km) of Saturn, Cassini engineers have been slowly adjusting the spacecraft’s orbit since January. They do this by flying Cassini near Saturn’s large moon Titan. The moon’s gravity pulls on the spacecraft, changing its direction and speed.

On November 29, Cassini will use a big gravitational pull from Titan to get into an orbit that is closer to perpendicular with respect to the rings of Saturn and its equator. This orbit will send the spacecraft slightly higher above and below Saturn’s north and south poles, and allow it to get as close as the outer edge of the main rings – a region as of yet unexplored by Cassini.

This graphic illustrates the Cassini spacecraft's trajectory, or flight path, during the final two phases of its mission. The view is toward Saturn as seen from Earth. The 20 ring-grazing orbits are shown in gray; the 22 grand finale orbits are shown in blue. The final partial orbit is colored orange. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute | › Larger image

Why It’s Important

Cassini’s ring-grazing orbits will allow scientists to see features in Saturn's rings, up close, that they’ve only been able to observe from afar. The spacecraft will get so close to the rings, in fact, that it will pass through the dusty edges of the F ring, Saturn’s narrow, outermost ring. At that distance, Cassini will be able to study the rings like never before.

Among the firsts will be a “taste test” of Saturn’s rings from the inside out, during which Cassini will sample the faint gases surrounding the rings as well as the particles that make up the F ring. Cassini will also capture some of the best high-resolution images of the rings, and our best views of the small moons Atlas, Pan, Daphnis and Pandora, which orbit near the rings' outer edges. Finally, the spacecraft will do reconnaissance work needed to safely carry out its next planned maneuver in April 2017, when Cassini is scheduled to fly through the 1,500-mile (2,350-kilometer) gap between Saturn and its rings.

› Read more about what we might learn from Cassini's ring-grazing orbits.

These orbits are a great example of scientific research in action. Much of what scientists will be seeing in detail during these ring-grazing orbits are features that, despite Cassini’s 12 years at Saturn, have remained a mystery. These new perspectives could help answer questions scientists have long puzzled over, but they will also certainly lead to new questions to add to our ongoing exploration of the ringed giant.

Teach It

As part of the Cassini Scientist for a Day Essay Contest, students in grades 5-12 will write an essay describing which of these three targets would provide the most interesting scientific results. › Learn more and enter

What better way to share in the excitement of Cassini’s exploration than to get students thinking like NASA scientists and writing about their own questions and curiosities?

NASA’s Cassini Scientist for a Day Essay Contest, open to students in grades 5-12, encourages students to do just that. Participants research three science and imaging targets and then write an essay on which target would provide the most interesting scientific results, explaining what they hope to learn from the selected target. Winners of the contest will be featured on NASA’s Solar System Exploration website and get an opportunity to speak with Cassini scientists and engineers via video conference in the spring.

More information, contest rules and videos can be found here.

The deadline to enter is Feb. 24, 2017.

Explore More

- Find educational lessons and activities about Saturn

- Discover free educational materials and resources about Saturn

- Students can discover more about Saturn with these slideshows, games and videos

- Download this timeline featuring milestones from Cassini's mission at Saturn or explore the interactive version!

- Explore the Cassini mission to Saturn website

- Browse our Cassini news archive

TAGS: Cassini, Saturn's Rings, Saturn, Grand Finale, Spacecraft, Missions, K-12, Lessons, Activities, Language Arts, Science, Essay Contest